Welcome to your one-stop shop for all your questions about Thanksgiving. Well, not including any questions about food. Or questions about the first Thanksgiving. Really, it’s more a run-down of how the U.S. Presidents have shaped the Thanksgiving holiday. Let’s dive in, shall we?

Welcome to your one-stop shop for all your questions about Thanksgiving. Well, not including any questions about food. Or questions about the first Thanksgiving. Really, it’s more a run-down of how the U.S. Presidents have shaped the Thanksgiving holiday. Let’s dive in, shall we?

Jefferson vs Lincoln: How the Holiday Was Born

It all began on September 25, 1789, when Congressman Elias Boudinot proposed a Congressional resolution to recommend a National Day of Thanksgiving be announced by President George Washington. This resolution was adopted and on October 3rd, President Washington issued a proclamation marking November 26th as “a day of public thanksgiving.”

Washington’s declaration, however, was a one-time event and not an annual occurrence. He didn’t issue another one until 1795, and that day was in February. Meanwhile, John Adams proposed his own days of “fasting and humiliation” in the spring of 1798 and 1799.

The nation’s next President, Thomas Jefferson, abhorred days of Thanksgiving for their religious connotations and avoided declaring any during his tenure. Somewhat ironically, the ceremony was brought back by the man who helped Jefferson build that wall between Church and State, James Madison. During the War of 1812, President Madison celebrated a day of Thanksgiving in 1814 and 1815, with neither date occurring in November.

Thanksgiving as we know it was largely the work of writer Sarah Josepha Hale, who waged a public campaign for years to add it as a national holiday. On November 26, 1863, during the midst of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln declared a national Thanksgiving day.

This time the tradition stuck, and in 1870 Congress passed and President Ulysses S. Grant signed, a law making New Year’s Day, Christmas Day and Thanksgiving national holidays in the District of Columbia. According to this law, Thanksgiving would be “any day appointed or recommended by the President of the United States.” This provision would become quite important later.

Franksgiving and How Thanksgiving Became the Fourth Thursday of November

Over the next seventy or so years, the familiar Thanksgiving rituals took root in America. So much so that when President Franklin Roosevelt sought to move the holiday in 1939, there was a massive uproar. On the advice of retailers who wanted more time for Christmas shopping, President Roosevelt moved the date up a week. This shift wreaked havoc on a number of levels, including collegiate football schedules, which used to end with Thanksgiving Day rivalry games back then.

FDR’s move was seen as a power grab, Atlantic City’s GOP Mayor called it ‘Franksgiving’, and it inflamed partisan passions. For instance, an August 1939 Gallup survey found a narrow majority of Democrats (52% to 48%) supported the move, while a vast majority of Republicans (79% to 21%) were opposed.

That first year only 23 states and D.C. shifted their date, while 22 states stayed put, and three states celebrated both. By 1940, the hold-outs were down to 16 states: (Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, Vermont). This group consisted of 9 Republican Governors and 7 Democratic Governors, out of the national total of 18 Republicans and 30 Democrats.

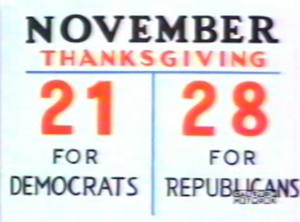

Warner Bros. would mock, and immortalize, this partisan divide in one of their Merrie Melodies cartoons. The episode featured a calendar that identified November 21st as Thanksgiving ‘For Democrats’ and November 28th as Thanksgiving ‘For Republicans’.

Warner Bros. would mock, and immortalize, this partisan divide in one of their Merrie Melodies cartoons. The episode featured a calendar that identified November 21st as Thanksgiving ‘For Democrats’ and November 28th as Thanksgiving ‘For Republicans’.

By 1941, President Roosevelt was forced to concede the battle and admit that no retail boom was created. With his support, Congress set out to make Thanksgiving once again the final Thursday of November (24th to 30th). That was how the original House resolution was written when it was passed on October 6, 1941. Yet by the time the resolution was brought up in the Senate two months later, it included an amendment to make Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday of November (22nd to 28th).

Why the change? That was Senator Robert Taft’s question when the amendment was brought to the floor. It seems that “Mr. Republican” was concerned that the Senate was compromising between the historical Thanksgiving date and Franksgiving. His fellow Republican from Connecticut John Danaher attempted to explain the change:

We in the Senate Judiciary Committee thought that, taking into account those 2 years in 7 when the last Thursday might be the last day of the very month of November, we would do better if we fixed the fourth Thursday, which would make it, in 5 out of 7 years, the last Thursday in November, and in the other 2 years would at least remove Thanksgiving Day from so close a proximity to the 1st of December as to make it possible for businessmen to know they were out of the red before they gave thanks. [Laughter.]

Despite Taft’s apparently well-founded doubts, the amendment was passed by voice vote. Perhaps everyone felt there were larger issues on the agenda, given that this occurred on December 9, 1941. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, FDR’s address to a Joint Session of Congress, and the declaration of war against Japan had all taken place over the past forty-eight hours.

On December 19, then-Congressman Estes Kefauver shepherded the resolution through the House by voice vote. A week later, on the same day that Winston Churchill addressed another Congressional Joint Session, President Roosevelt signed the Thanksgiving resolution into law.

How the Presidential Turkey Pardon Became A Tradition

From the Civil War up through World War II, the Thanksgiving Day Proclamation was the President’s primary ceremonial duty for the day. Now that the date was officially set, however, the President was in need of a new stunt. As the Era of Mass Media slowly developed, the annual delivery of turkeys to the White House represented a golden photo opportunity for the President to give some brief remarks and supply an eye-catching picture for the newspapers.

Now those old photos with Presidents Truman and Eisenhower posing with turkeys, the ones that pop up every year alongside the annual turkey pardon stories, may leave the impression that the tradition started then. On the contrary, it most emphatically did not. In fact, by all indications, those particular turkeys likely ended up in Presidential stomachs.

The first unofficial turkey pardon came in 1963, when a turkey was presented to President John F. Kennedy with a sign proclaiming ‘Good Eating, Mr. President!’ The image-conscious Kennedy, apparently repulsed by the grim spectacle, spontaneously pledged to spare the bird. Maybe because this occurred on November 19, 1963, JFK’s final show of mercy remained stuck in the minds of the press corps and historians.

The first unofficial turkey pardon came in 1963, when a turkey was presented to President John F. Kennedy with a sign proclaiming ‘Good Eating, Mr. President!’ The image-conscious Kennedy, apparently repulsed by the grim spectacle, spontaneously pledged to spare the bird. Maybe because this occurred on November 19, 1963, JFK’s final show of mercy remained stuck in the minds of the press corps and historians.

Over the next few years, almost imperceptibly, the turkeys that were delivered to the White House ceased being diner guests. This transition was encapsulated by President Reagan who joked (at least, I think it was a joke) that he was going to eat the turkey presented to him in 1981. By the end of his tenure, Reagan was making it clear that this particular turkey would leave 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue unharmed.

Although in 1987, one especially memorable ceremony took place. Reagan’s appearance coincided with rumors that he would pardon Oliver North and other participants in the Iran-Contra Affair on Thanksgiving Day. When Sam Donaldson used the occasion to ask Reagan about the reports, the President quipped that he would’ve pardoned them if they’d spared the turkey.

Despite Reagan’s ad-lib, the situation remained unchanged. Presidents had pardon power, they received a turkey every Thanksgiving and let it go, but for whatever reason no one ever bridged the gap. That is until November 17, 1989, when some enterprising members of the Bush White House realized that they could further maximize this photo op. That day President Bush proclaimed that “this fine tom turkey…he’s granted a Presidential pardon as of right now.”

So while it turns out that Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez is older than the Presidential turkey pardon, it nevertheless quickly became a practically sacrosanct tradition. It’s probably not a coincidence either, that the event’s rising relevance was simultaneous with the growth of cable news. The light-hearted ceremony was perfect for 24/7 channels, not to mention national and local news segments, as the Clinton and Bush 43 presidencies unfolded. During the Obama years, the First Daughters made the occasion an online hit in the viral video age. It even managed to be one of the few traditions Trump maintained, and last week, Biden continued the custom by pardoning his first bird.

Of course the truest measure of impact today is pop culture references, and the Presidential turkey pardon is well-represented in that regard, with parodies in shows as diverse as The West Wing and Rick & Morty. Ultimately, the Presidential turkey pardon is guaranteed to last until the moment a future Administration comes up with a better photo op.