In April California’s Secretary of State Shirley Weber announced that the campaign against Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom had enough signatures to trigger a recall election. Weber’s office finalized and officially confirmed the recall petition’s success on June 23rd. On July 1st Lieutenant Governor Eleni Kounalakis announced a recall date of September 14th, leaving just ten weeks for those in favor of recall and the potential replacement candidates to mount campaigns.

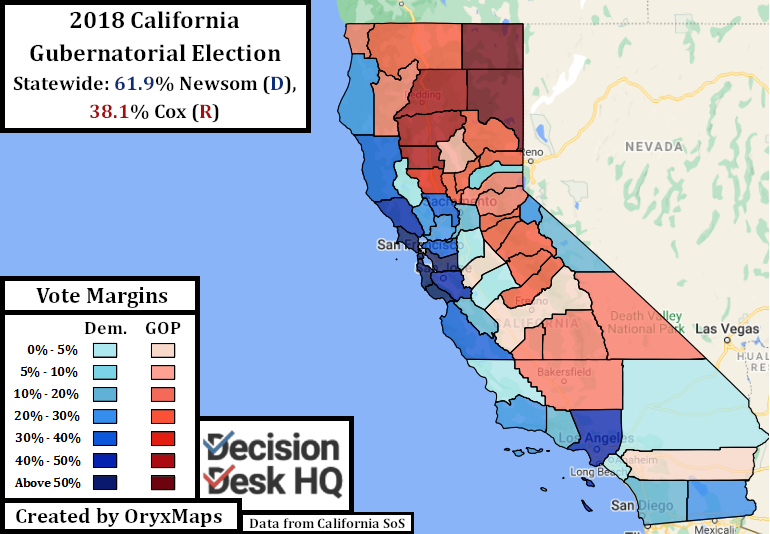

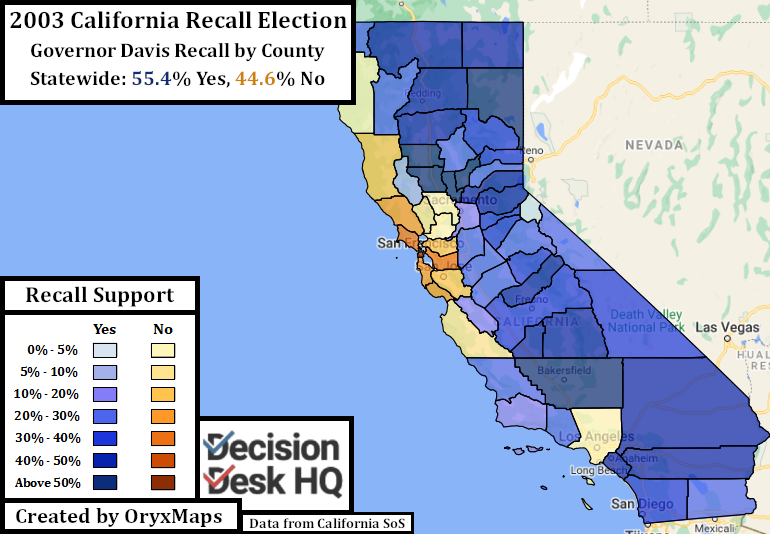

This is the second statewide recall election in California’s history. It is natural to compare this election to the 2003 gubernatorial recall election, when voters replaced incumbent Democratic Governor Gray Davis with Republican action star Arnold Schwarzenegger. Yet the 2003 and 2021 recall elections have few similarities. Governor Davis suffered from low approval ratings, barely won reelection in 2002, faced divisions within the State Democratic party, and governed a state with an electorate amenable to electing Republicans. Today, Newsom enjoys positive – but not universally positive – approval ratings, won the 2018 election by 61.9% to 38.1% – a margin comparable to the average modern Democrat, has a united Democratic party, faces a disunified Republican party opposition, and is Governor of the fifth-most Democratic state in the nation. Newsom will retain his office if present circumstances continue. Overriding external events must nullify or negate these advantages before California voters will recall and replace Governor Newsom.

The Lack of a Motivator

All notable California statewide officials face recall petitions. California’s immense population contains enough angry activists to launch an initiative, but very few of these petitions receive the funding and attention necessary to attract significant numbers of signatories.

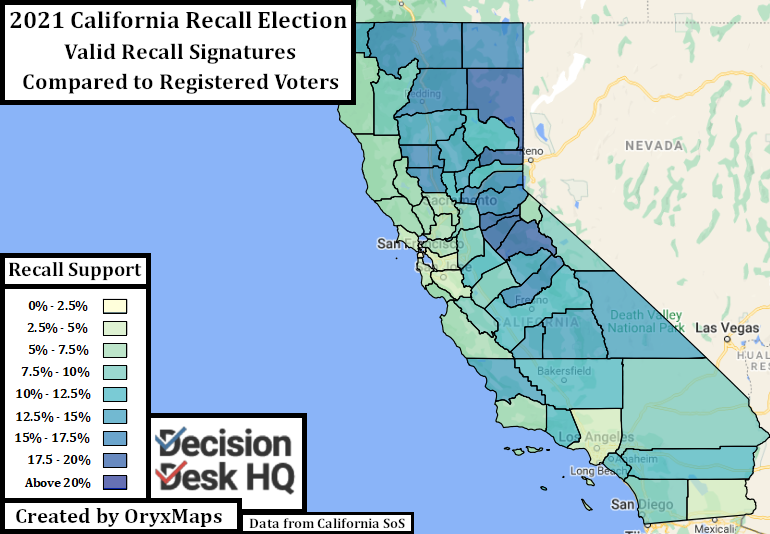

This recall petition against Governor Newsom gained traction as an outlet to express conservative anger towards California’s coronavirus policies. Many signed the petition after Newsom broke his own health guidelines in November 2020 to attend a private party at The French Laundry, a Michelin star-rated Napa County restaurant. California faced surging coronavirus cases, leading many of Newsom’s detractors to label him an aloof hypocrite. Over 90% of signatories added their names to the recall petition after Newsom’s blunder. The French Laundry fiasco gave the recall campaign the attention and grassroots funding it needed, precipitating the recall campaign.

Newsom’s initial bad press and scandals gave way to success and recovery. California fully reopened on June 15th. Newsom announced a $75.7 billion budget surplus, which justified the state sending out its own state stimulus check to residents. State vaccination rates are up and deaths are at all-time lows – partially because of accommodating vaccination policies, and partially because of numerous state and local incentives for the hesitant.

In 2003, in contrast to today, California’s electricity crisis and budget shortfalls following the dot-com bust permanently damaged the public perception of Governor Gray Davis. Several issues nearer to election day denied him any chance at a comeback: an unpopular vehicular license tax increase implemented to close the state budget, accusations of corruption and ties to the energy companies, and widespread wildfires and declarations of emergency in Southern California.

Similarly overarching and disruptive events must occur for the 2021 recall campaign to regain momentum. Large-scale wildfires, a surge of Coronavirus variants and reimposition of statewide restrictions, or a national media cycle that damages Democrats nationwide are possible undermining events for Governor Newsom’s campaign.

Party Unity and Electoral Divisions

The California recall vote takes the form of two questions: should Governor Newsom be recalled, and if so, who should replace him? This dichotomy between the recall campaign and the replacement campaigns divides potential contenders. Victory only comes through cooperation and coordination between the campaigns on both sides of – and off – the ballot.

Former Governor Gray Davis fought the 2003 recall campaign without a united Democratic front. His unpopularity necessitated passing parochial legislation in 2003 to try and win back groups of Democratic voters apathetic to his candidacy. Democratic Lieutenant Governor Cruz Bustamante ran as a replacement candidate for the recall, a decision prompted by Davis’ poor retention prospects and Bustamante’s personal disapproval of his superior. Bustamante’s campaign undermined the “No” on recall campaign – the nature of his candidacy was a concession that voters would recall Davis and needed a Democratic alternative.

Republicans united behind the candidacies of Hollywood actor Arnold Schwarzenegger and then-State Senator Tom McClintock. Schwarzenegger emerged as the favorite in the final weeks of the campaign and consolidated undecided voters. Other prominent Republicans, including former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan, Congressman Darrel Issa, and former Secretary of State Bill Jones, stayed out of the race to avoid splitting the limited base of California’s Republicans. Party unity allowed both candidates to stand above the more than 100 attention-craving gadflies on the replacement ballot, consolidating votes.

The electoral organization of the 2021 recall is incomparable to the 2003 recall. Governor Newsom is popular enough. The entire state and national Democratic Party support “No” on the recall campaign. No serious Democratic rival has yet entered as a potential replacement, and none likely will. Entry would prompt ostracization from the Democratic party, and the chance of a successful replacement campaign remains low. Los Angeles mayor Eric Garcetti, a rumored potential rival, has downplayed talks of the recall and instead aims for an appointment as President Biden’s ambassador to India. The lack of a prominent Democrat is intentional – Democrats do not want a repeat of the Bustamante campaign and instead seek to force their voters to vote “No” if they want a Democratic governor. Part of this strategy involves the recall ballot stating Newsom’s Democratic identification, and the Governor’s office is suing the Secretary of State to implement this delayed 2019 provision.

The Republican and “Yes” campaign positions remain fragmented. The recall campaign began as a partisan Republican proposal, but became an outlet for outrage. The initiative never gave up its Republican roots – the “Yes” campaign’s financial support remains mainly Republican. Republican Orrin Heatlie, a former police officer, heads the “Yes” effort, even though his initial partisan motives cannot win statewide. The “Yes” campaign presently focuses on perceived corruption and statewide issues – such as housing, homelessness, farm access to water, etc – in an attempt to bring needed Democratic voters into their camp. This approach attempts to separate the recall effort from the ideological candidates on the replacement ballot.

The partisan core of the recall effort pushed numerous Republicans to run as potential replacements. Among the most prominent Republicans are: 2018 GOP Gubernatorial nominee John Cox, former San Diego mayor Kevin Faulconer, reality TV personality Caitlyn Jenner, former Congressional Representative Doug Ose, and State Assemblyman Kevin Kiley. Unannounced but potential Republican candidates include: President Trumps’ ambassador to Germany Richard Grenell, talk radio host Larry Elder, and Trump-aligned political commentator Mike Cernovich. None have any meaningful cross-party appeal, none can seriously define themselves as separate from their fellow Republicans, and the field’s prestige degrades with each new entrant.

The low $4000 barrier to entry means that the GOP candidates share the ballot with over 50 – and likely many more – unknown attention-craving candidates. No GOP candidate has emerged from this pack of humiliating competitors, and the clownish actions of candidates like Cox (who has campaigned with both a live Kodiak Bear and an 8-foot-tall ball of trash) tarnish the entire field. This time, there is no candidate like Schwarzenegger who enjoyed universally favorable name recognition and access to the resources necessary to campaign across the state, and it seems unlikely one will emerge. Nobody with such appeal has any incentive to challenge Newson’s favorability or associate themselves with the ever-expanding mess of replacement candidates.

The Skeptical Electorate

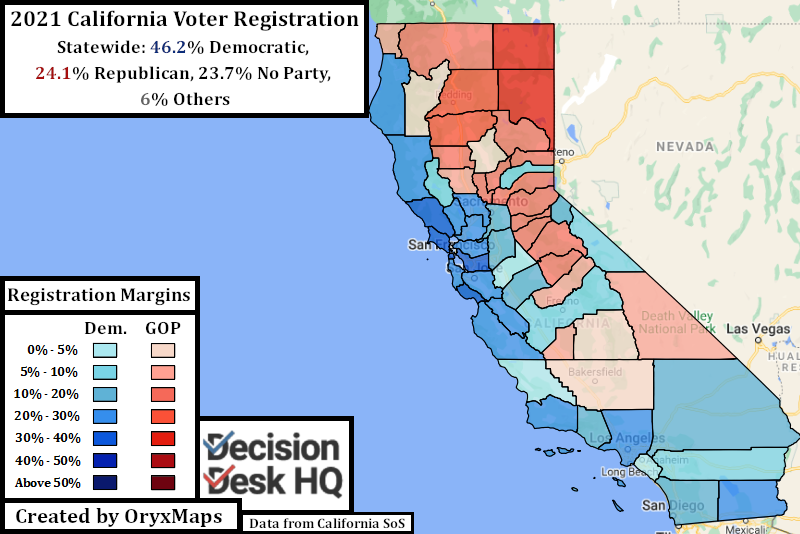

The challenge facing any prospective Californian campaign is whether or not it can attract part of the overwhelming Democratic majority. Candidate Biden’s 29-point margin in 2020 yielded his campaign a margin of five million votes. Registered California Republicans trail registered Democrats by the same five-million vote margin, and they trail those voters unaffiliated or registered with a minor party by over one-million voters. Newsom has not lost any side of his previous coalition. Those Democratic-aligned voters that disapprove of him lack a reformist alternative.

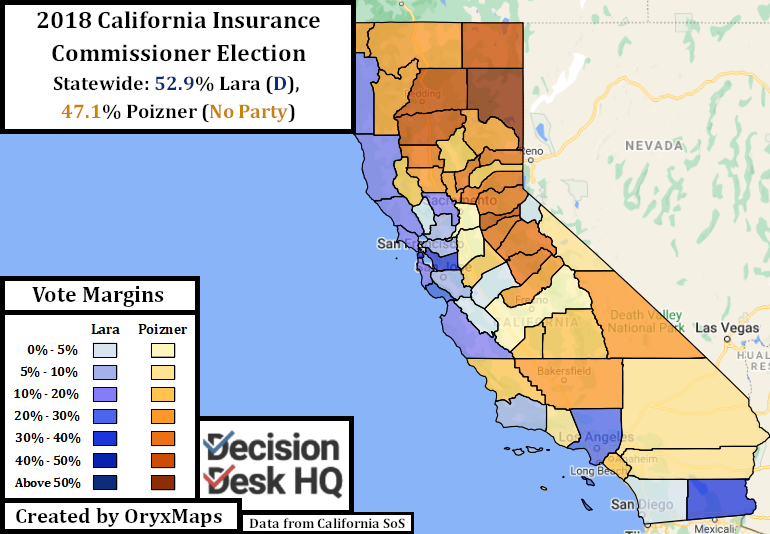

More than enough of these statewide voters are committed Democratic partisans. The Republican party used the 2018 Insurance Commissioner race as an attempt to gauge whether California could elect non-confrontational, managerial Republicans similar to Governors Phil Scott in Vermont and Charlie Baker in Massachusetts. Steve Poizner, the Republican-endorsed candidate, had almost every advantage. He ran as an independent abandoned by the GOP, he was running for an office he had previously occupied and managed successfully, he had a base in Democrat-dominated Silicon Valley, the Insurance Commissioner was separated on the ballot from the topline Democrats by other statewide races, Poizner won endorsements from Democrat-leaning organizations and newspapers, and Poizner faced a factionalized Democratic candidate with limited ties statewide. Still, Poizner lost. Partisan Democrats were too numerous.

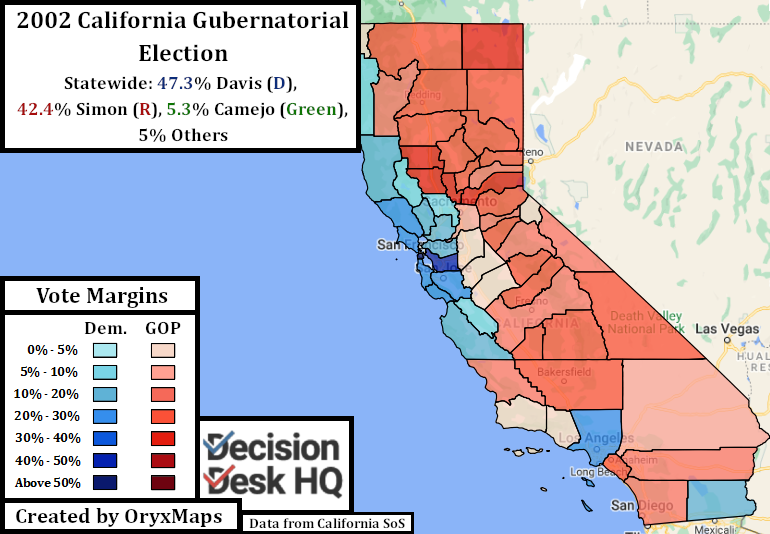

This contrasts with the 2003 recall. Republicans lost all statewide races in 2002 – many by narrow margins – but they had won both the Secretary of State’s office and the office of Insurance Commissioner in 1998. Richard Riordan held the Los Angeles mayor’s office from 1993 to 2001. Major offices were not yet out of reach.

Republican strength in California was once built upon the suburbs and outlying cities around Los Angeles. The end of the Cold War closed or downsized many of the research and military-adjacent industries across the region, prompting a slow exodus of partisan Republican families to areas of potential employment. Former Los Angeles residents moved into these cheaper properties, transforming the partisanship of these suburbs and opening up space in the cities for new Democratic-aligned immigrants. Compton for example, is today 68% majority-Hispanic, with descendants of the city’s former African American families migrating to the Antelope and San Bernardino valleys to the north and east. This trend had yet to finalize in 2003, and the GOP still could find votes in outlying cities like Long Beach and Riverside.

Working in favor of the recall campaign is the Democratic Party’s decision to hold the election at the earliest date acceptable to County boards. Holding the election sooner rather than later reduces the possibility of surprises upending the race, but it lowers the Democratic floor and ceiling. Southwestern Democrats struggle to match normal turnout among low-income minority voters during abnormal elections. Partisan Republicans in favor of the recall, by contrast, will be motivated to vote. It will not likely matter in the end, but the decision to not hold the election in November slightly shifts the composition of the electorate against Newsom.

In Newsom’s favor though is a law that mandates all registered voters will receive a mail ballot for any election held in 2021. This requirement might increase overall turnout, but 2020 demonstrates that certain groups will still struggle to utilize this system or return their ballots.

The Trajectory of the Campaign

Much must change before the California electorate recalls Governor Newsom. Events beyond any politician’s immediate control must damage the governor, a transformational candidate from any party or faction must enter the race with enough money and name recognition to sideline bickering opponents, and Newsom must lose parts of California’s Democratic base to the recall campaign. As long as Californians view Newsom favorably no prominent Democrat or liberal independent will enter the field, consolidating Democratic support behind his “No” on recall campaign. The race so far has appears near California’s 60% Democrat 40% Republican off-cycle partisanship, with even some partisan GOP polls finding Newsom ahead of the “Yes” campaign. If the recall election continues on its current trajectory, Newsom will remain governor by a wide margin.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.