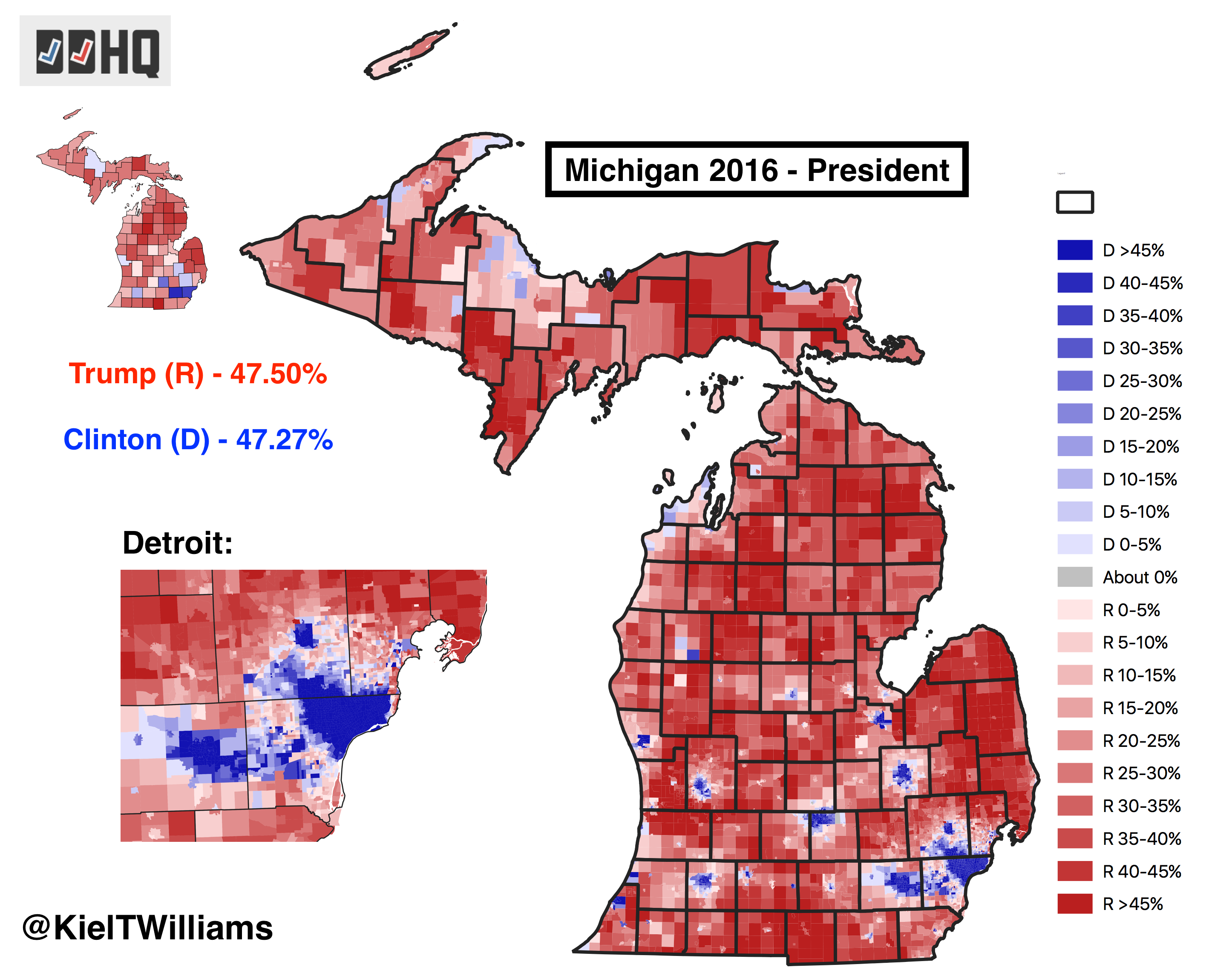

Donald Trump’s narrow victory in Michigan was one of election night 2016’s bigger surprises. Despite its perennial battleground status, Michigan had not voted for a Republican presidential candidate since George H. W. Bush in 1988. Few 2016 forecasters thought Donald Trump was likely to break the streak. He proved many of them wrong, when his deep rural support – combined with reduced Democratic urban turn-out – propelled him to victory.

Democrats rely on large margins in the big cities – Detroit, Ann Arbor, Flint, and Lansing especially – to win statewide elections in Michigan. Anything that reduces the Democratic margin in those key urban areas is enough to put Republicans within spitting-distance of victory. Indeed, that’s exactly what happened in 2016: Hillary Clinton failed to win Detroit and its outlying suburbs by as large a margin as Obama in 2008 and 2012. Other Michigan cities witnessed similar trends. These smaller urban victory margins – combined with Trump’s monolithic support in the more rural northern part of the state – were enough to earn Republicans a narrow victory.

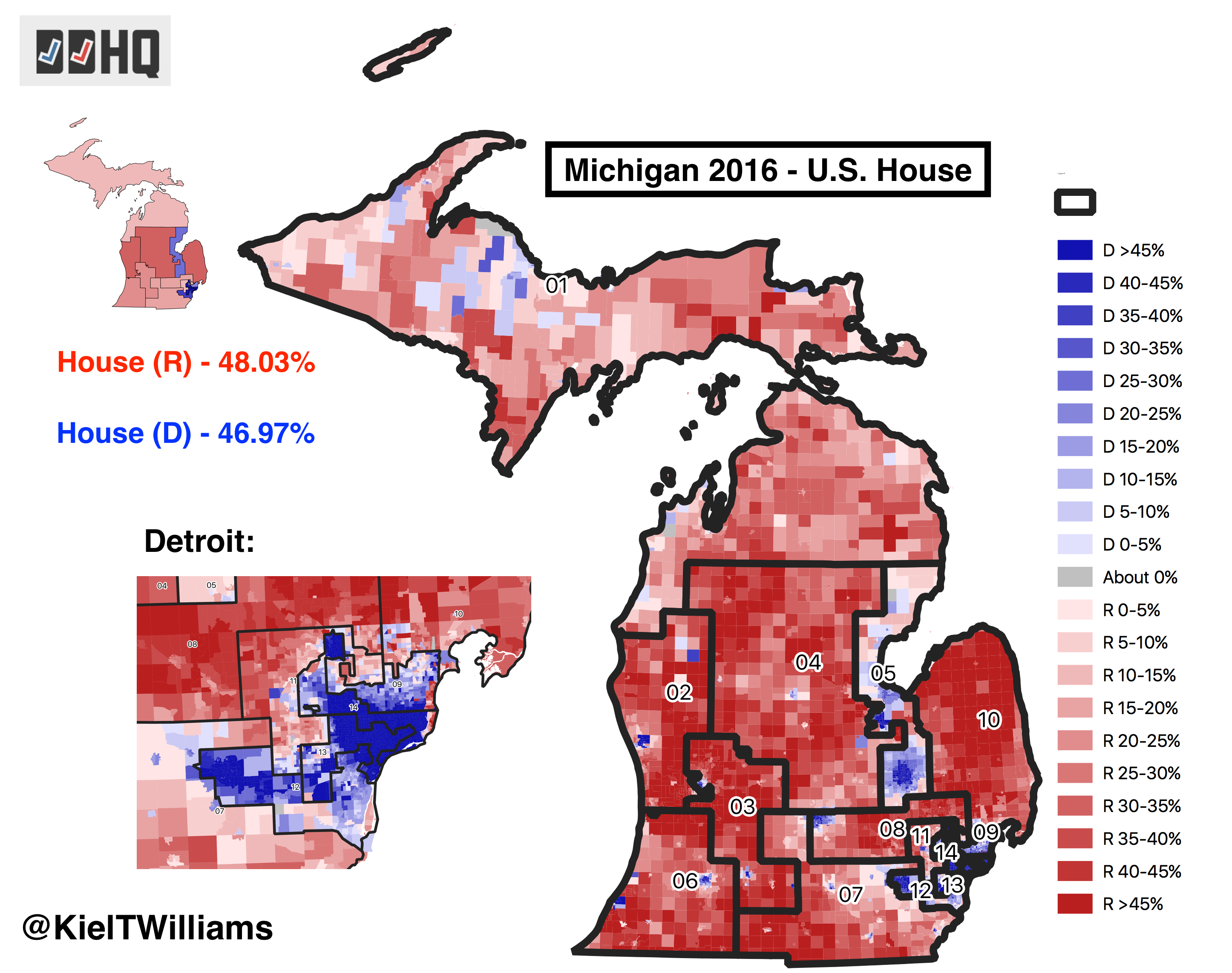

At the same time, 2016 saw no partisan change in Michigan’s 14-member delegation to the U.S. House. Much of the Michigan House map would not be competitive in any environment: districts 9, 12, 13, and 14 share the heart of Detroit, and are safely Democratic (though it’s easier to imagine MI-9 becoming competitive in the future). Similarly, districts 1, 2, 3, 4, and 10 are rural Republican strongholds.

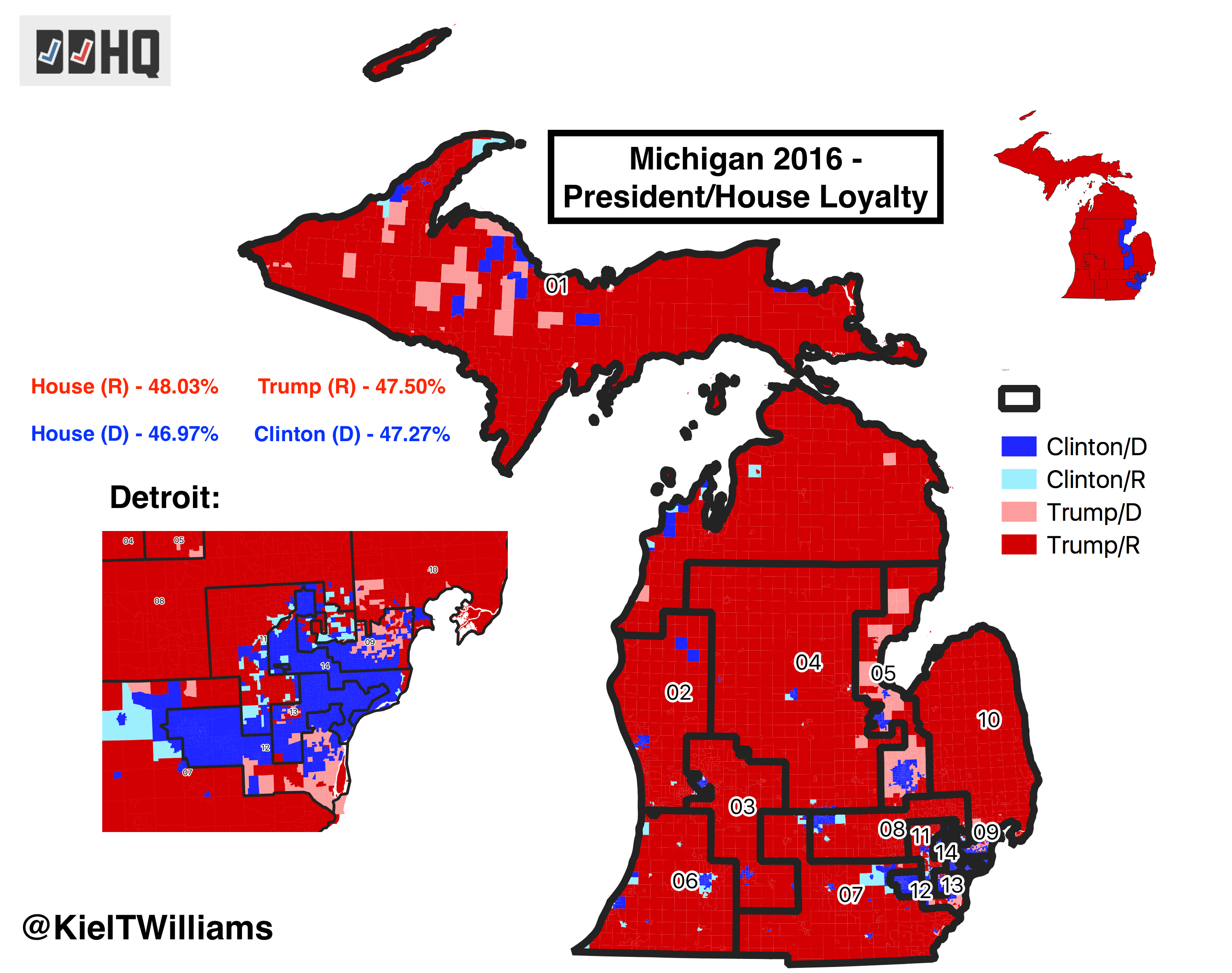

A loyalty map between the 2016 presidential and House elections provides some insight about why Clinton lost, and suggests the House seats that might be competitive in 2018. First, we see that Hillary Clinton hemorrhaged Democratic votes on the northeastern and southeastern edges of Detroit (light red). Even as these voters easily reelected their Democratic House Representatives – primarily Sander Levin in MI-9 and Debbie Dingell in MI-12 – many of them defected to Donald Trump at the presidential level. Dan Kildee (D) also dramatically outran Hillary Clinton in his Flint-based MI-5 district, winning there by 26 points, even as Clinton won by only 4.

The most likely seat to change partisan hands is probably Rep. Mike Bishop’s Rochester- and Lansing-based MI-8. Mike Bishop – who has represented his district since 2014 – was reelected by a wide 17-point margin in 2016. But a number of precincts in his district bordering Lansing and Rochester split their vote between him and Hillary Clinton. Bishop faces a stiff challenge from former Assistant Secretary of Defense Elissa Slotkin, who has thus far out-raised him. The Øptimus legislative model currently gives Bishop a 72% chance of survival.

Retiring Rep. Dave Trott’s (R) MI-11 district – in the outlying area around Detroit – is also likely to be competitive. Despite Trott’s 13-point reelection in 2016, many of the more-urban precincts in his district also voted for Hillary Clinton. This is the kind of district where it’s easy to imagine suburban dissatisfaction with Trump redounding to Democrats’ benefit. Businesswoman Lena Epstein (R) is challenging former Obama Administration official Haley Stevens (D) to succeed the outgoing Trott. The Øptimus model currently gives Republicans an 82% chance of holding the seat.

Finally, Democrats’ last opportunity to flip a Michigan House seat is probably MI-7, where Rep. Tim Walberg (R) faces a rematch with Michigan Representative and former Saline mayor Gretchen Driskell (D). Walberg – who defeated Driskell by 15 points in 2016 – would not be endangered in a typical election. However, his district includes some Clinton-supporting western suburbs of Ann Arbor and Lansing, so a large-enough Democratic wave might get Driskell over the finish line. Her fundraising has been comparable to Walberg’s. The Øptimus model currently gives Driskell a 25% chance of winning the seat.

(Correction: The maps in the first version of this article contained several errors that have been fixed.)