Missouri Senator Claire McCaskill’s (D) race against state attorney general Josh Hawley (R) is one of the key races that will decide control of the Senate in this November’s midterm election. Despite Missouri’s steady march to the right, McCaskill has persisted, serving as state auditor from 1998 until 2006, when she narrowly defeated Sen. Jim Talent (R) in the 2006 Democratic wave.

While she has undoubtedly benefitted from her political skills, she has also benefitted from some of the most remarkable luck of any politician in modern times. Her first senate victory in 2006 came at the height of public anger at the GOP over Iraq. She did not have to face voters during the 2010 and 2014 GOP waves, when it’s doubtful she could’ve survived. And then during her 2012 reelection, her opponent Todd Akin’s (R) campaign imploded after his comments about rape. Of course, McCaskill herself helped to engineer Akin’s candidacy, so attributing her success to luck is somewhat unfair.

With McCaskill’s next election right around the corner, it’s interesting to consider the 2012 political environment in Missouri, and what it might mean for today.

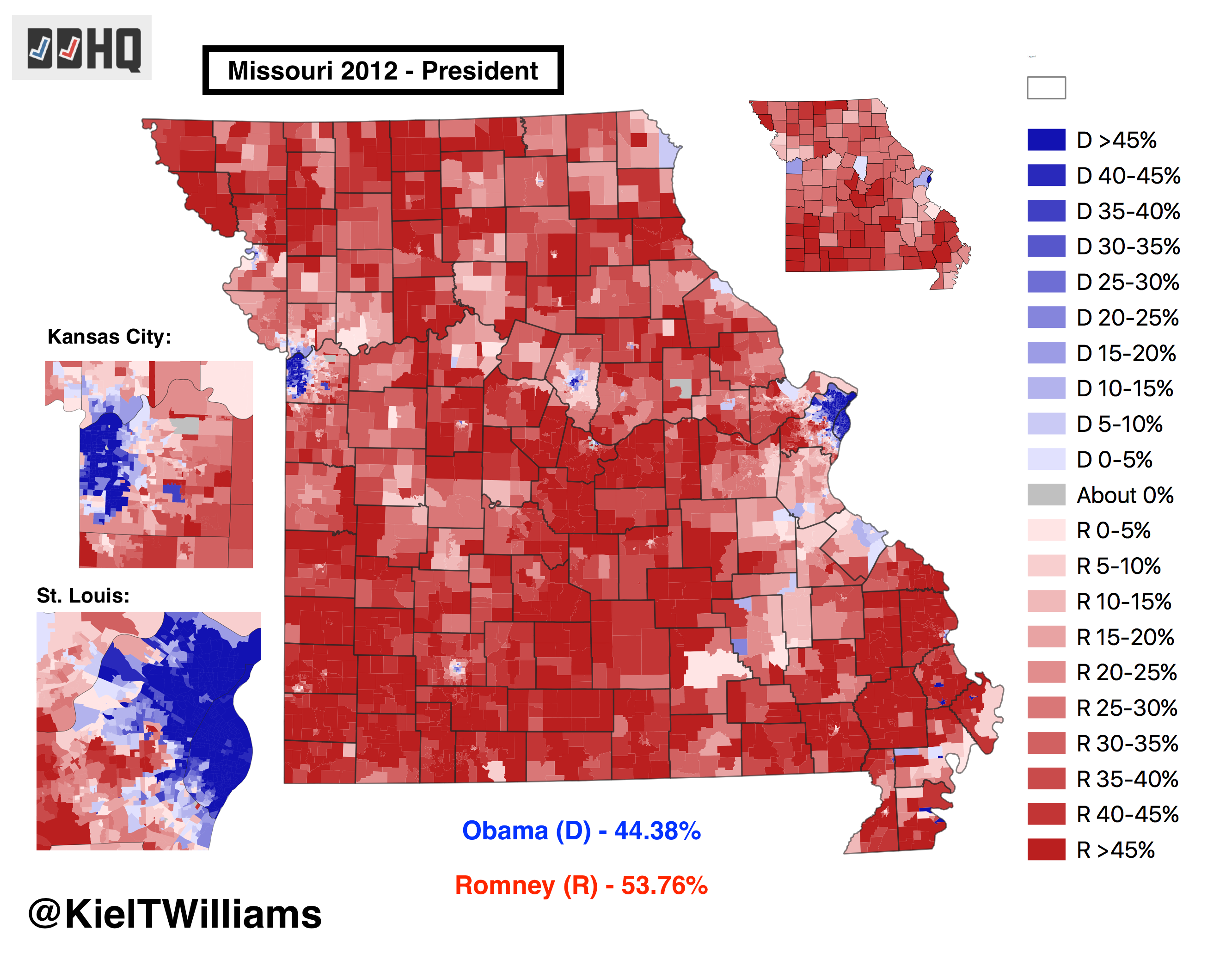

Despite its ancestral Democratic roots, Missouri has trended strongly toward the GOP over the last several decades. Today, the state usually votes 9 points to the right of the country overall. Mitt Romney’s 9-point win here in 2012 closely reflects a generic Republican performance. Despite his severe losses in St. Louis and Kansas City, Romney’s large margins in suburban and rural regions propelled him to an easy victory.

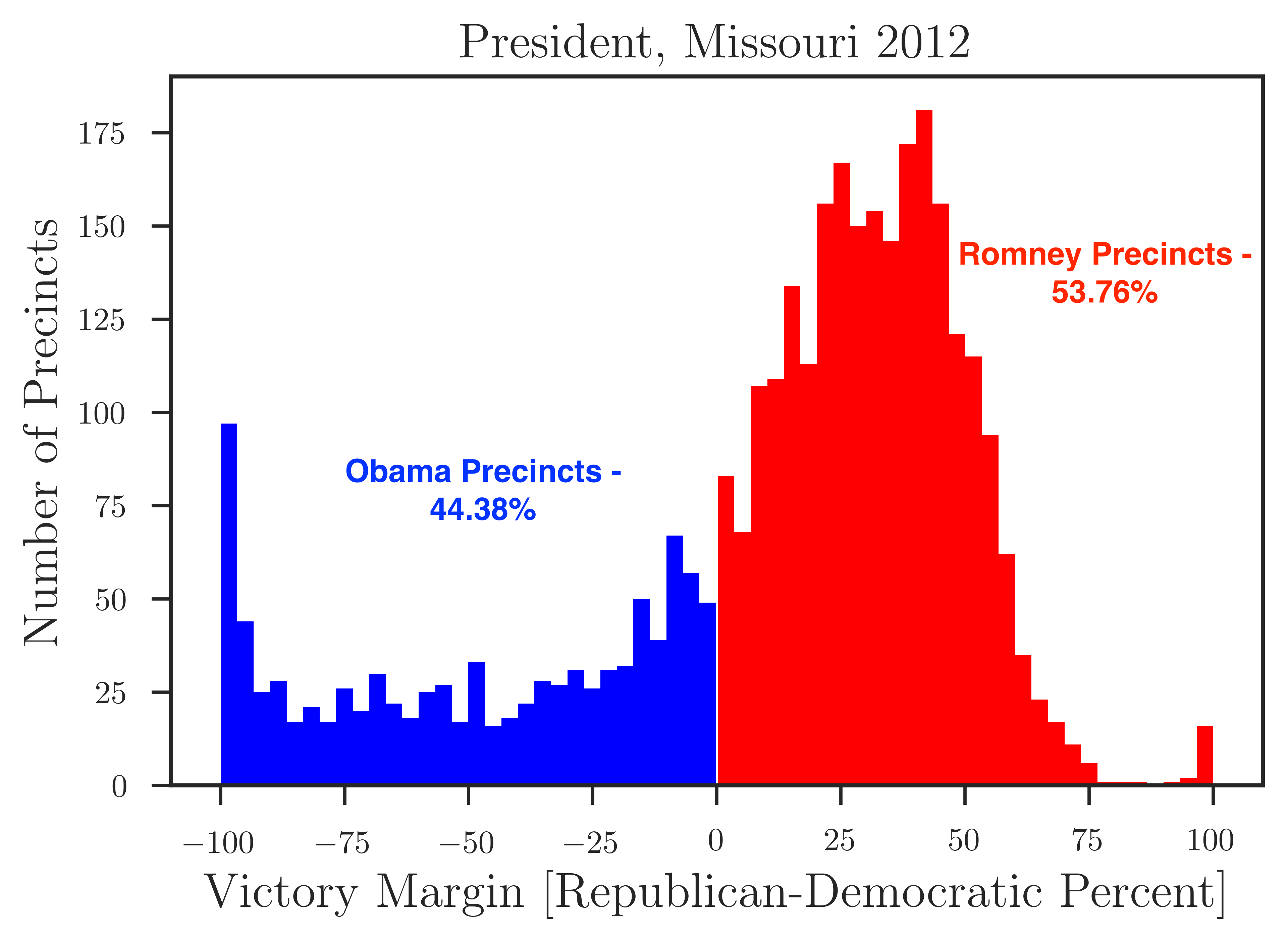

A histogram of precincts by victory margin demonstrates this even more clearly. Despite Obama’s strong performance in urban areas, he wasn’t able to overcome the large number of outlying regions where Romney routinely won by 30-points or more.

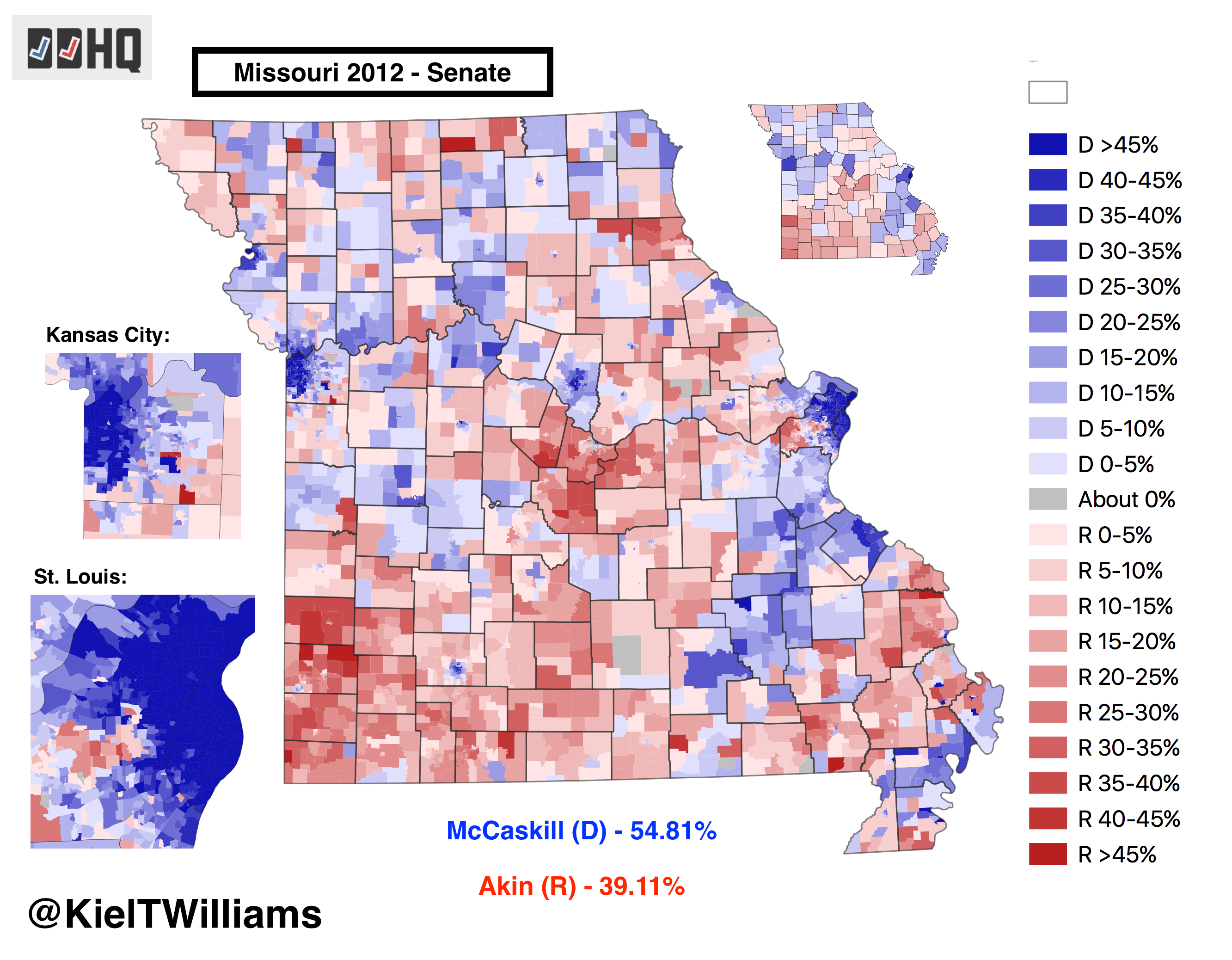

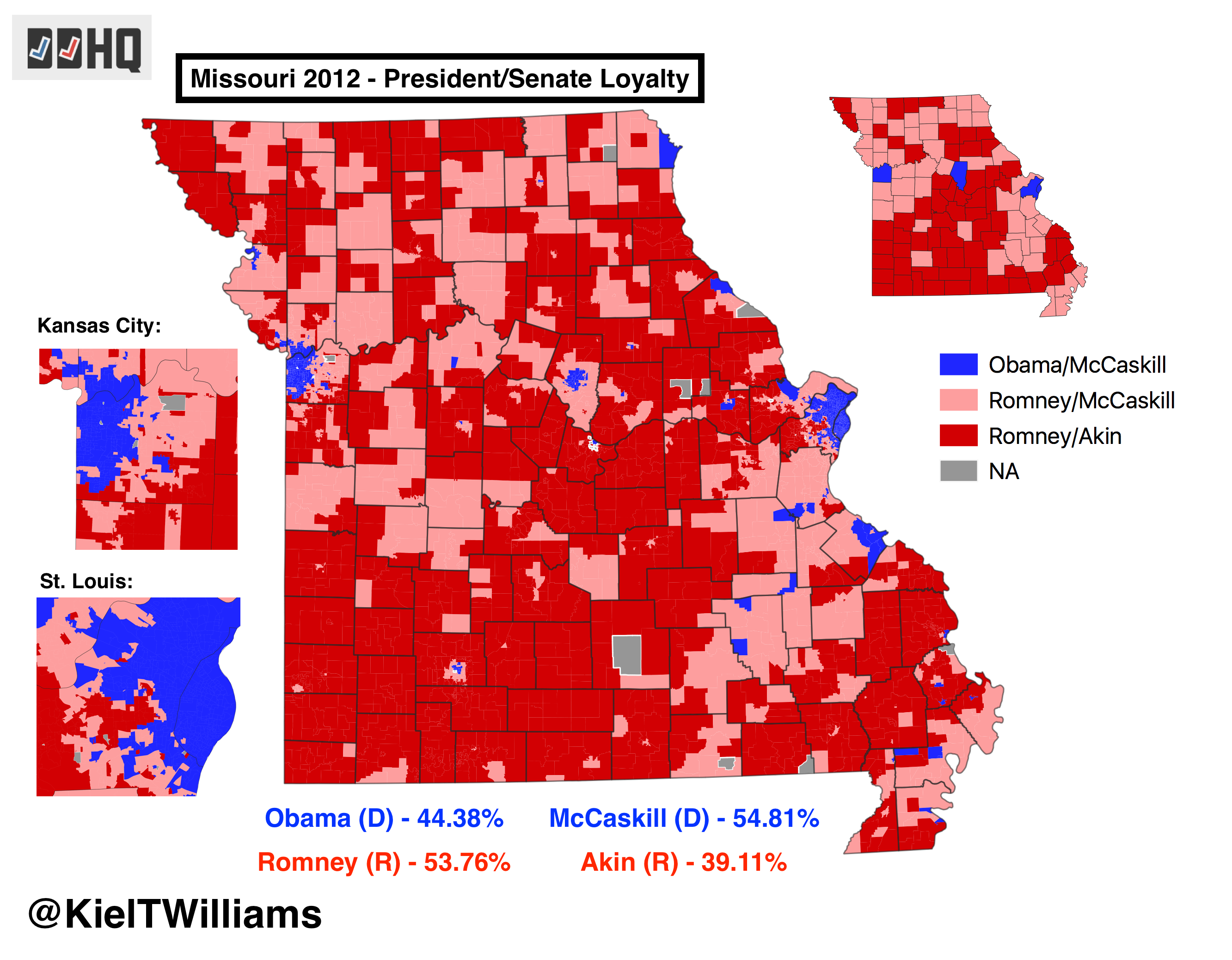

At the same time, McCaskill was also cruising toward what was ultimately an easy win. The suburban and rural voters who supported Romney abandoned Todd Akin, partially at the behest of Romney himself. While Obama’s support was confined to the core urban centers, McCaskill successfully carried outlying areas, and lost rural parts of the state by much smaller margins.

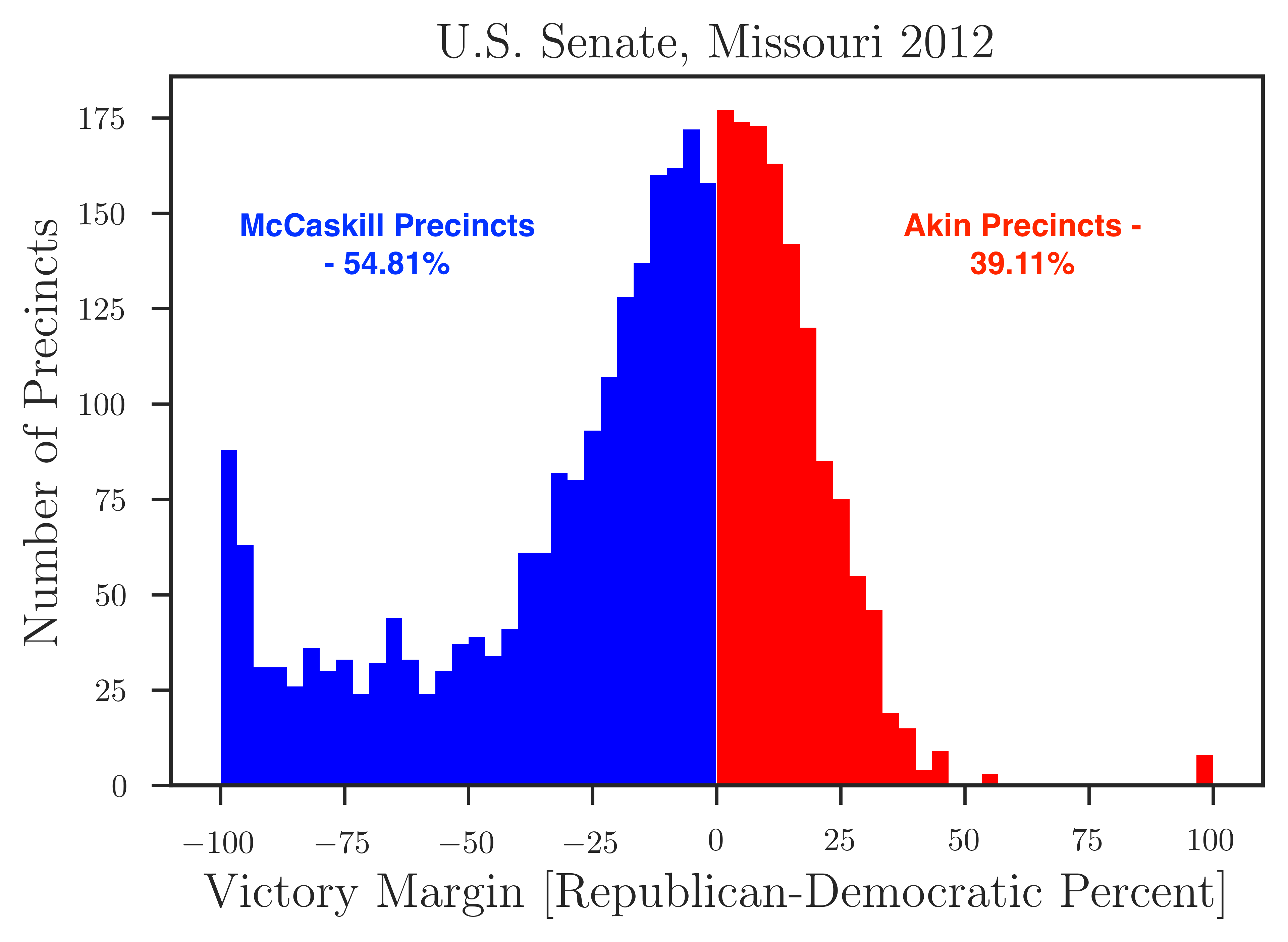

McCaskill’s cross-over appeal appears dramatically in the voting distribution for the Senate race. In stark contrast to Romney, Akin hardly carried any precincts by more than 25 points. McCaskill remained very competitive in Republican-leaning precincts (the bump centered around zero), while also running-up large margins in urban areas (the left-tail of the chart).

A loyalty map comparing Obama and McCaskill demonstrates the same trend. Rural voters – particularly in the northern and southeastern part of the state – simultaneously backed Romney and rejected Akin en masse.

Barring a complete meltdown of Josh Hawley’s campaign over the next few months, McCaskill has little hope of replicating her 2012 performance. On the contrary, the 2012 secretary of state election actually paints a more realistic picture of what a McCaskill win could look like in 2018.

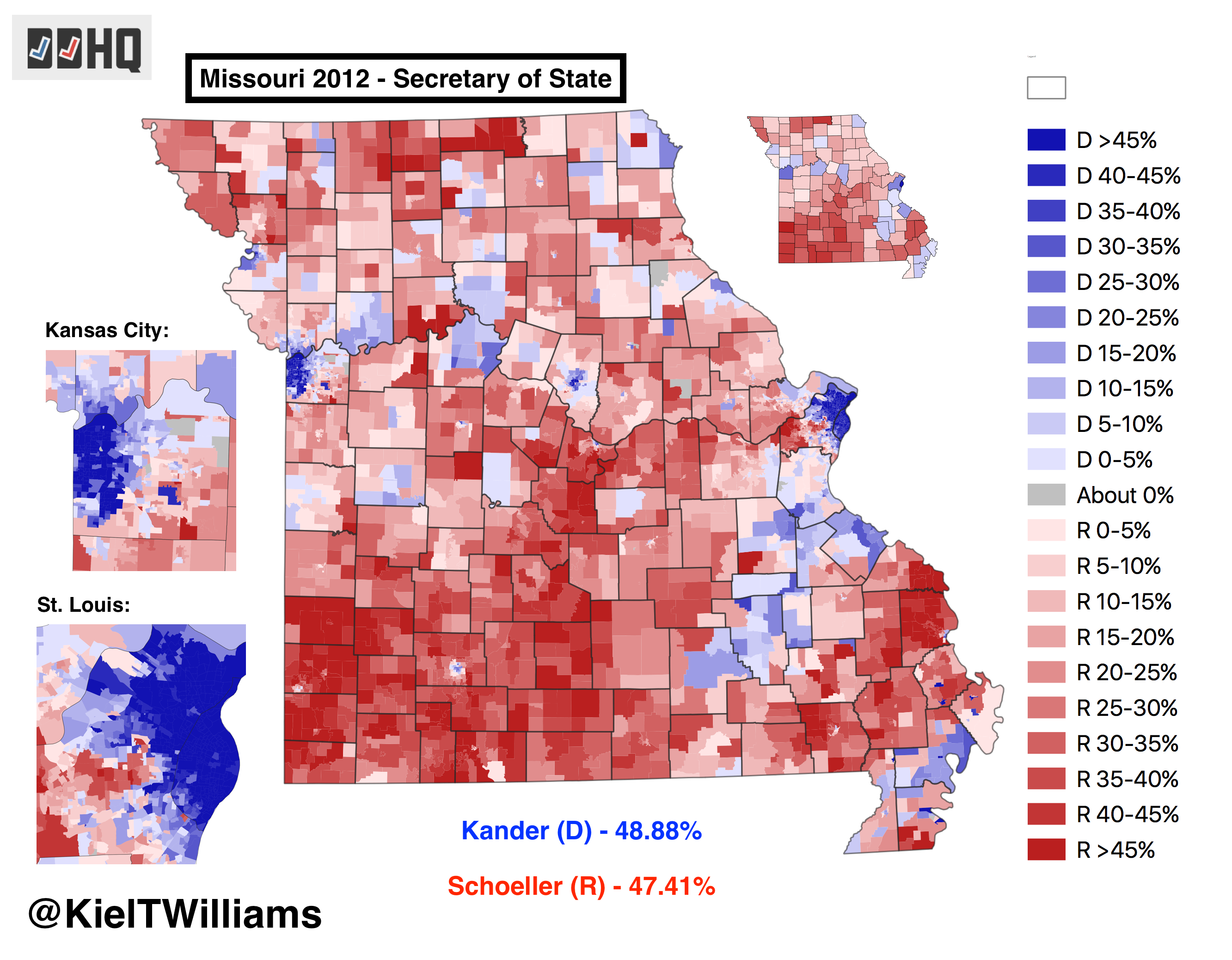

Jason Kander (D) – now more famous for his unsuccessful 2016 senate campaign – narrowly won the Missouri secretary of state’s office in 2012 against state representative Shane Schoeller (R). Unlike Akin, Schoeller presented himself as a generic Republican, and posted the rural precinct margins to show for it. However, Kander was able to win urban areas by impressive margins, while also remaining somewhat competitive in outlying areas around the big cities. Jefferson county – just south of St. Louis on the eastern border – emerges as a good bellwether in this analysis. Every winning statewide candidate carried this county in 2012, including Kander by 2 points.

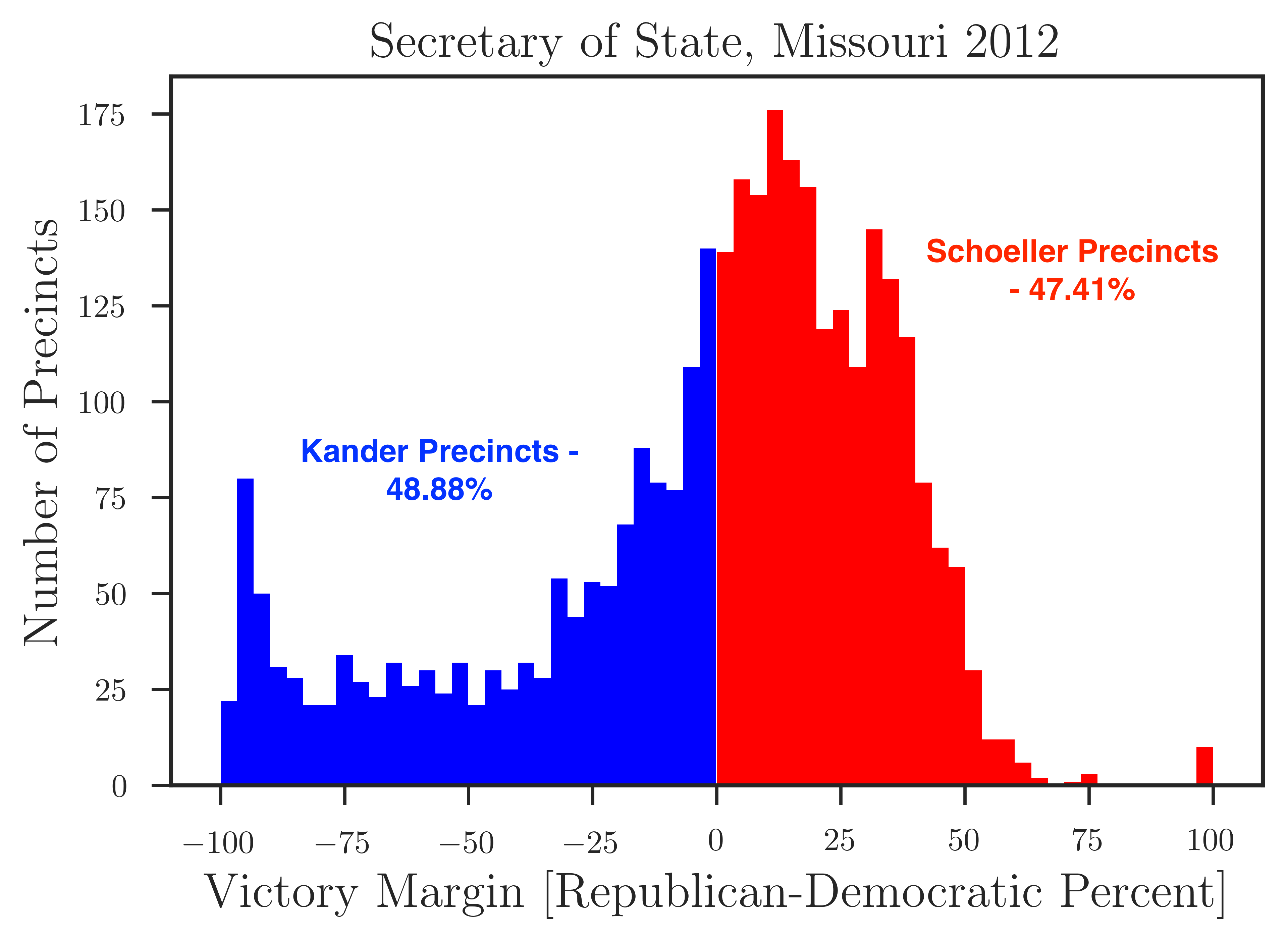

The structure of Kander’s victory comes out more clearly in the precinct voting distribution. While Schoeller won a lot of rural precincts, he tended to win them by only about 15 points, in contrast to the 30-point margins Romney produced.

Finally, 2012 illustrated the difficult state-of-play for House Democrats in Missouri. Todd Akin retired from his MO-2 House seat to run for Senate, and was easily succeeded by Ann Wagner (R). Of Missouri’s 8-member House delegation, Democrats hold only 2 seats: Emanuel Cleaver’s Kansas City-based MO-5, and Lacy Clay Jr.’s St. Louis-based MO-1.

Of Missouri’s 6 GOP-held House seats, only MO-2 – with an R+8 partisan lean – is even theoretically competitive. Even there, the Øptimus legislative model gives Democrats only a 30% chance of taking the seat. Regardless of the national environment, 2018 is unlikely to see any change to the Missouri House delegation.

Forecasters typically view the Missouri senate race as a pure toss-up. Thus far, McCaskill has substantially out-raised Hawley, though this gap is likely to narrow as election day approaches. Polls have consistently shown a close race. But given her fund-raising edge, her past performance, and the national environment, the Øptimus model is optimistic about her odds, giving her a 63% chance of reelection.

(Check-out my interactive map of Claire McCaskill’s 2012 senate victory! Featuring victory margins for every statewide race in every precinct.)