Two states, Oregon and Colorado, released preliminary redistricting maps on September 3rd. This first step in Oregon’s redistricting process involved releasing multiple, different maps, each drawn by a different group of state legislators. Colorado began its redistricting process months ago with public input forums for the state’s new redistricting commission. Colorado’s recent map is the second potential Congressional map put forward by the commission, but it bears little resemblance to the previous plan.

Both states’ proposed lines raise more questions than they answer. In certain places both state’s plans ignore the interests of larger communities in service of narrower objectives

Oregon

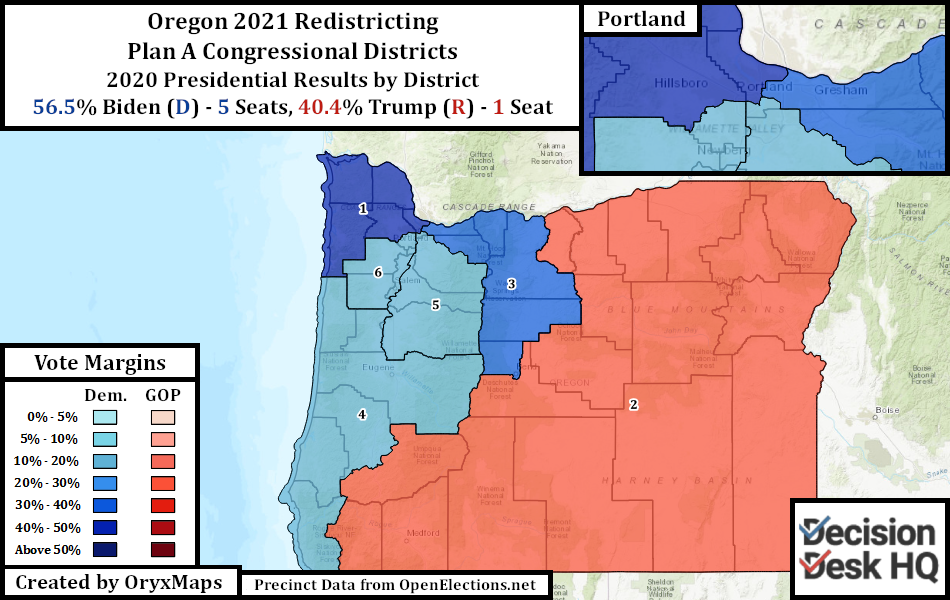

Oregon released three sets of maps. Each set contains plans for both chambers of the state legislature and two of the three contain proposals for Congressional districts. The state designated these plans as Plan A, Plan B, and Plan C.

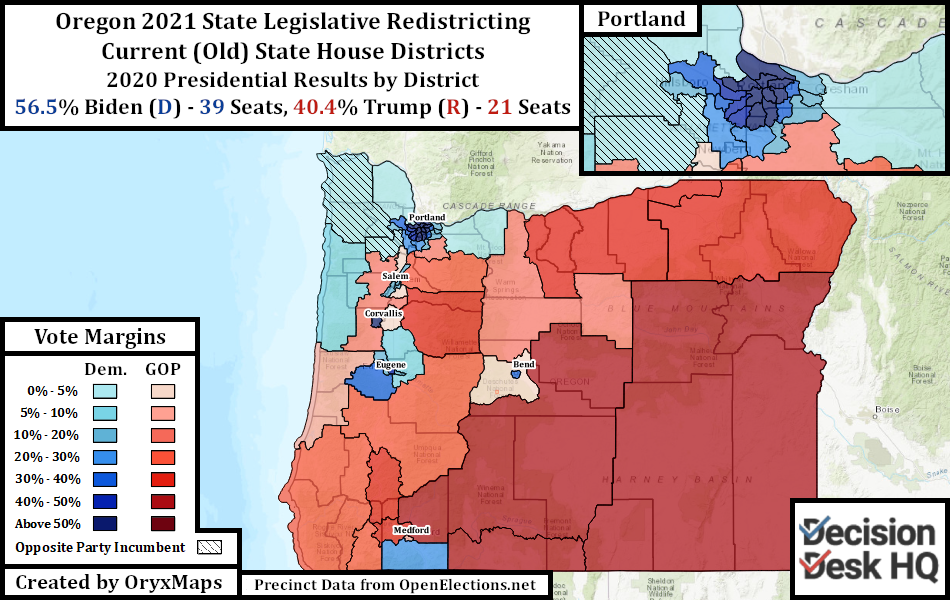

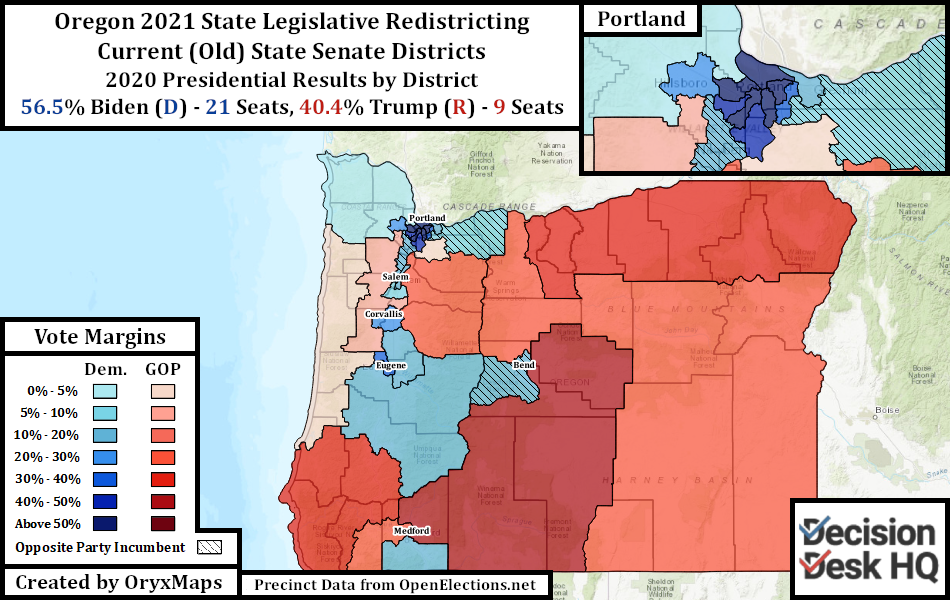

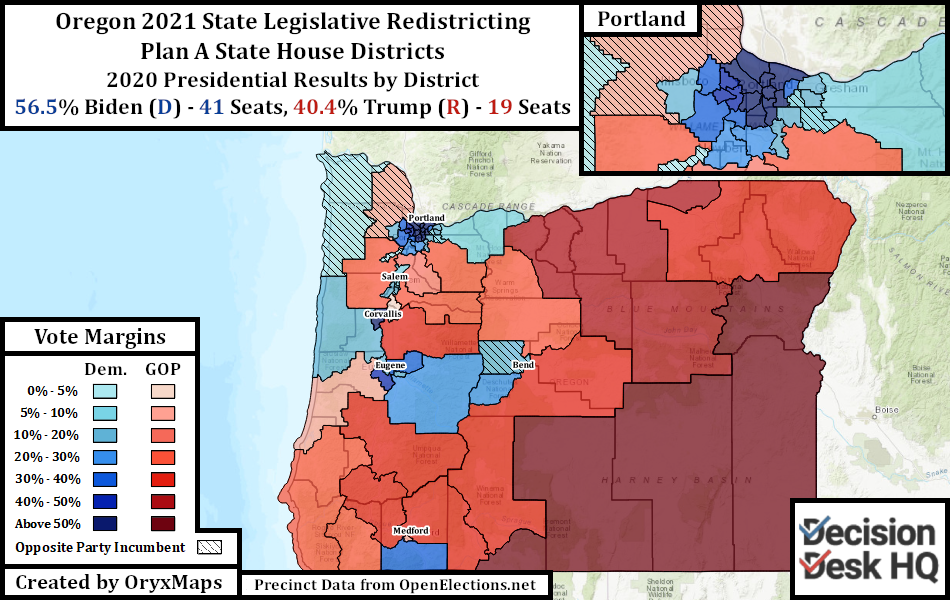

Oregon legislative redistricting follows the principle of “nesting.” The 60-seat State House of Representatives is twice the size of the 30-seat State Senate; each State Senate district contains two State House districts. Oregon additionally gained one Congressional district through reapportionment and now has six seats.

Partisan actors quickly defended the plan most favorable to their interests. Democrats argue that Oregon is a Blue state and an overwhelmingly Democratic set of outcomes is expected. Republicans argue that Oregon Democrats are concentrated in cities, and therefore outcomes will not be as favorable to Democrats as the topline suggests.

Both parties are right and wrong. Oregon has comparatively negligible partisan geographic advantage; neither party benefits from the distribution of their voters statewide. Democrats are concentrated in Portland and its suburbs; Republicans are concentrated in the rural south and east. Between these regions are several cities, college towns, and agricultural communities that favors no party overall. A Democratic map uses these intermediary cities to dilute neighboring Republican towns, while a Republican plan uses the surrounding towns and rural areas to counterbalance these urban voters.

These maps are preliminary proposals. If no agreement is reached and no maps are passed, power transfers to tiebreakers. Democratic Secretary of State Shemia Fagan decides legislative lines and the State Supreme Court (all Democratic appointees) decides congressional lines. With such divergent plans, a handover appears likely.

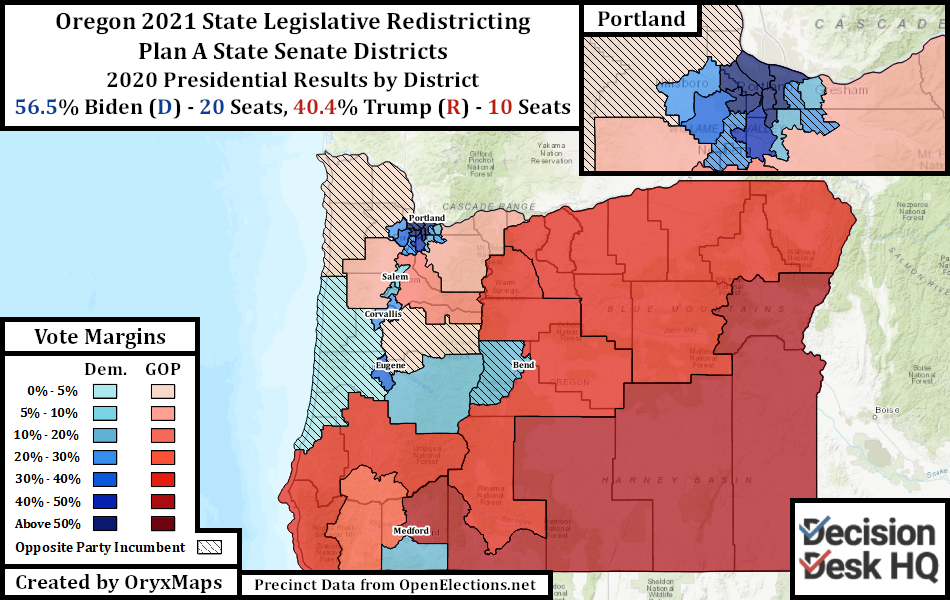

Plan A

The Oregon State Senate, controlled by Democrats, drew the Plan A maps. Democratic domination unsurprisingly meant Plan A’s maps are Democratic gerrymanders.

Plan A’s Congressional map is a gerrymander designed to elect five Democrats and one Republican. This outcome on its own does not make the map partisan: many hypothetical fair maps could produce this same outcome by Democrats sweeping marginal seats winnable by both parties. However, no Plan A Congressional seat are competitive. Four seats have a piece of Portland’s Democratic electorate, reinforcing the adjacent suburbs and outlying cities.

The proposed State Legislative maps intend to expand, but also reinforce Democratic majorities. Democrats do not currently hold every legislative seat President Biden won in 2020. Expanding margins in already-blue seats is more important than drawing more potential target, but the map does produce more Democratic seats overall.

To disperse the Democratic vote to previously marginal seats, Plan A carves up outlying cities to dilute neighboring Republican areas. Bend in eastern Oregon grew slightly too large for a single district, but the mappers split the city to create two blue State House seats. Four State House districts and three State Senate districts have pieces of college town Eugene. Three State House and two State Senate districts split the capital Salem. Multiple districts reach out of Multnomah County (Portland) into their less-Democratic suburbs.

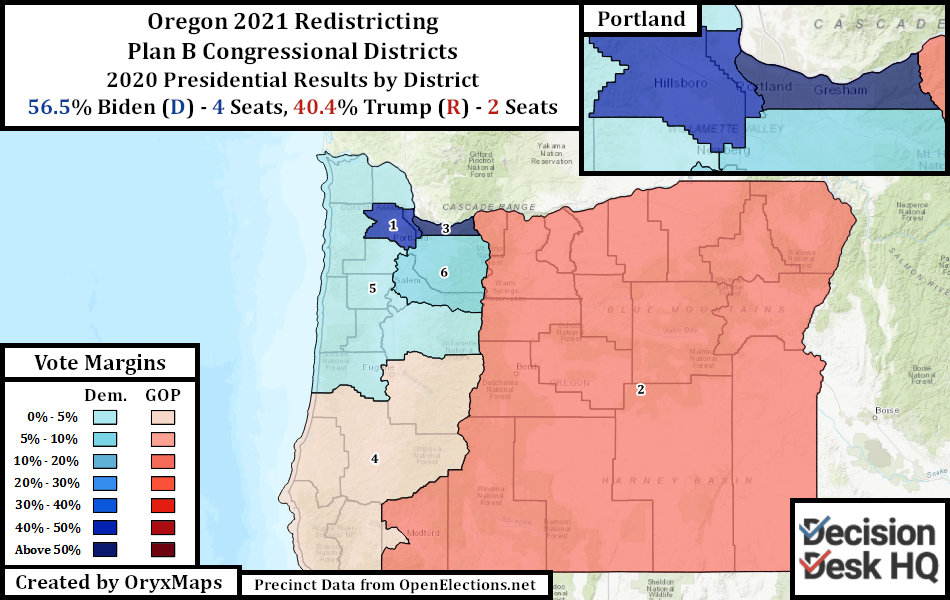

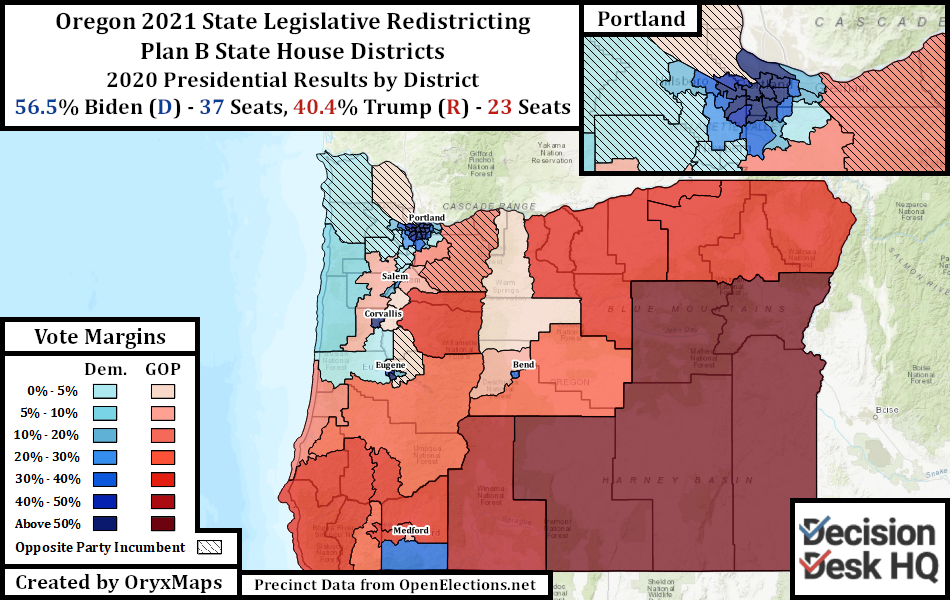

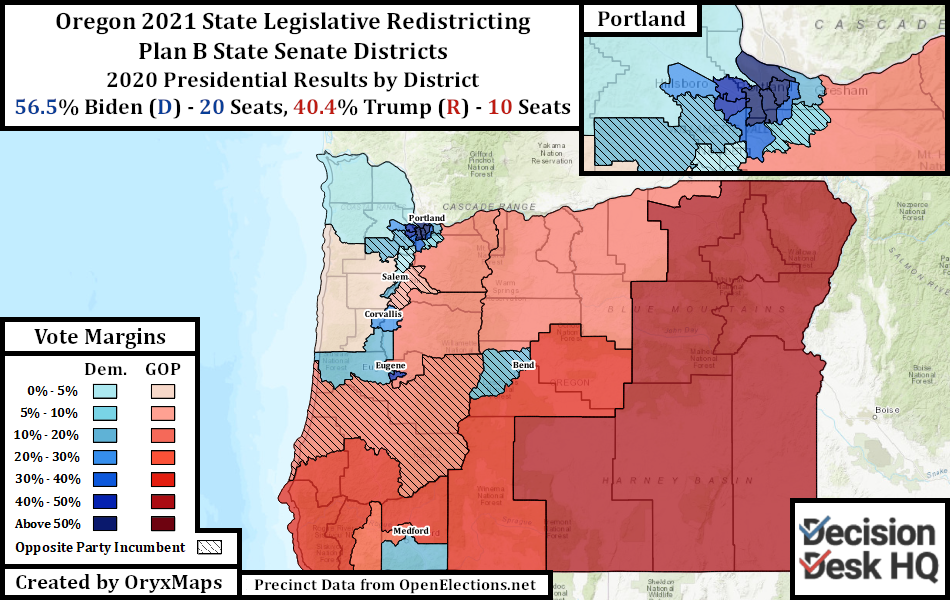

Plan B

Oregon State House Democrats initially struck a deal with State House Republicans in early April. The dominant Democrats agreed to allow Republicans into their mapping process. In exchange, State House Republicans agreed not to delay key legislative proposals. This bipartisan legislative committee could not agree on any proposals once in session, leading to the two committee factions releasing their own plans. Plan B is from the Republicans.

At first glance, Plan B’s Congressional lines appear less offensive than Plan A’s. Districts in Portland and the suburbs follow rational community lines, but that is where neatness stops. Districts Four and Five are specifically rural seats, each with only one Democratic city each, and each avoided taking in excess Democratic areas when possible. Former President Trump won both seats in 2016, making the map three Democrats to three Republicans. President Biden barely won just one of the two seats in 2020. There are many fair proposals with competitive districts that could produce an even partisan split, but an even split in Oregon should not be the most likely outcome. This map aims for that result by diluting the influence of college communities.

Plan B’s legislative proposals are just as partisan as Plan A. The topline results are similar to the present legislative maps, but Biden only marginally won many of Plan B’s districts. Republicans could win a majority in the State House with only minimal effort under Plan B, despite Oregon voting for Biden by over 15 points.

To produce this outcome, the map concentrates Democrats in outlying urban areas into the minimal number of districts, and then dilutes the remainder with rural areas. The mappers stated that “when you pair college students with small town residents 45 miles away to one party’s political advantage, that’s gerrymandering.” The inverse is also true.

Growing Bend drops the least Democratic neighborhoods into outlying districts, to keep the city concentrated into one State House seat. Democratic Hood River County is cut into two Republican districts in the proposal for both chambers. All of Eugene’s student neighborhoods are in one State House seat, so that multiple rural districts avoid the city and favor Republicans. Portland suburbs are carefully carved up so that overwhelmingly Democratic areas are in their own seats and marginally Democratic areas are paired with GOP communities.

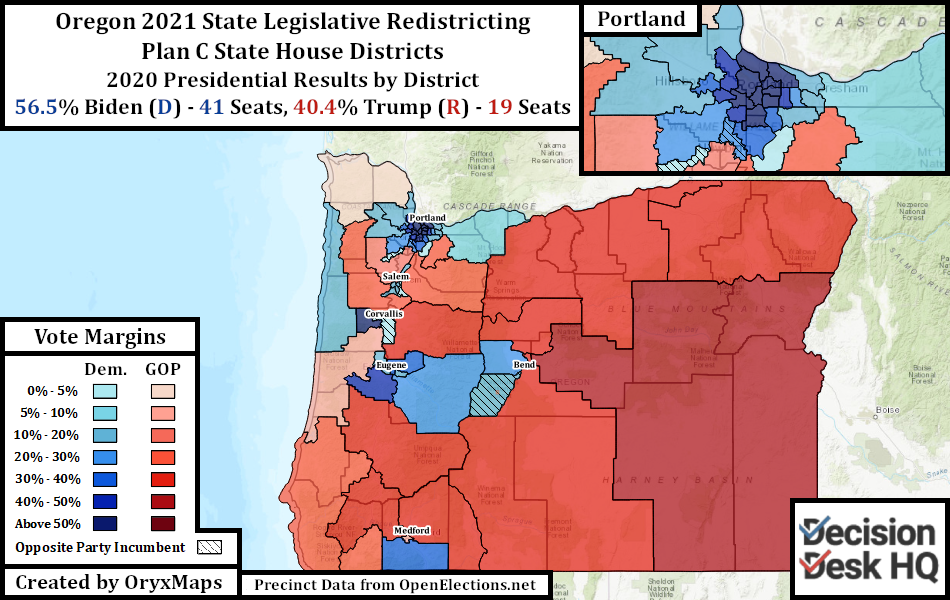

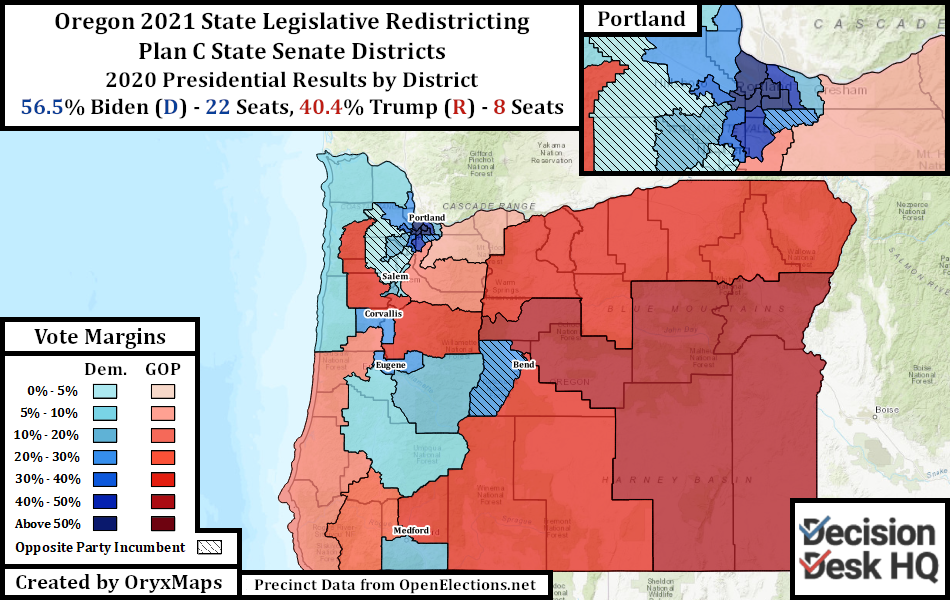

Plan C

The Democratic State House redistricting committee members drew the two maps comprising Plan C. The authors are three minority State Representatives and the maps specifically seek to increase minority voter access and opportunity. Plan C does not include a proposal for the six Congressional districts.

Plan C’s legislative lines partially resemble Plan A’s. The two plans are both drawn by Democrats, so Plan A and Plan C share some similarities. Bend is divided into two State House seats and both favor Democrats, like in Plan A. Eugene remains divided between four State House seats and three State Senate seats. Districts still extend from cities to absorb and dilute rural Republican voters.

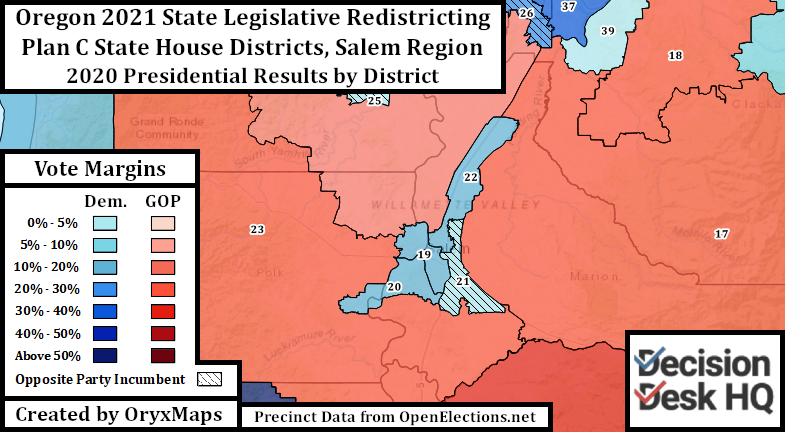

Plan C and Plan A diverge when it comes to Salem and urban Portland. Marion County (Salem) is home for a large number of self-identified Hispanics, both in outlying farming villages and in the urban city. State House Plan C reconfigures the Salem districts to increase the number of districts with sizable Hispanic populations and maximize Hispanic voting power inside the majority-minority State Senate district. Hispanic regions in other parts of the Willamette Valley are then grouped into seats responsive to the communities interests, even though these seats are not majority-minority.

Portland and her immediate suburbs are safe for Democrats. The metro area is also majority White. Maximizing minority opportunity therefore requires creating coalition districts with the few neighborhoods that have a significant minority presence. Coalition districts are seats where no single minority group has a plurality, but the sum of multiple minority groups demographically outnumber White voters. Other seats are reconfigured to give minority voters the opportunity to put forward a favored candidate, shifting the overall alignment of the urban seats from North-South to East-West.

Colorado

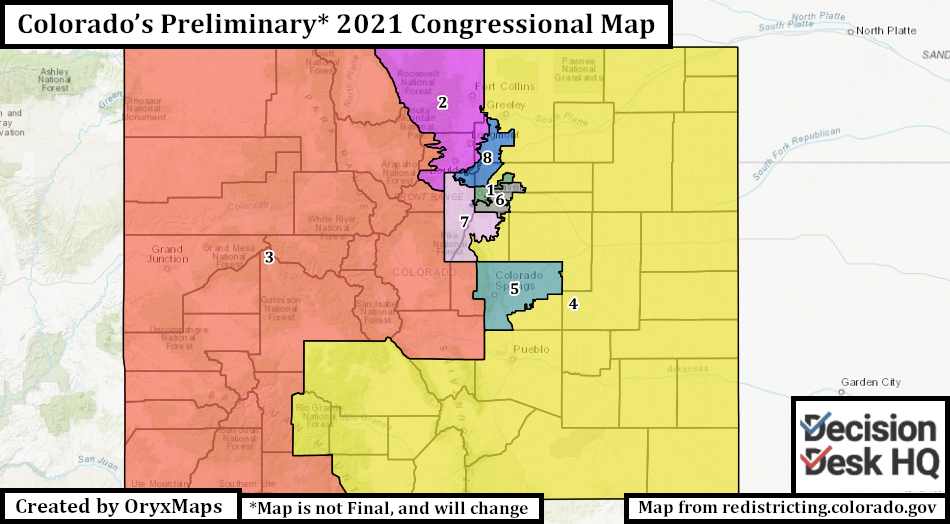

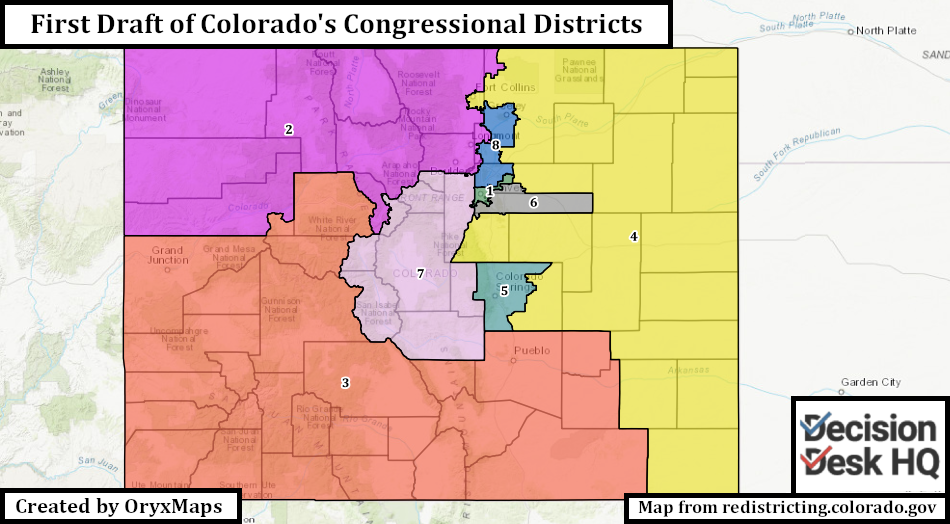

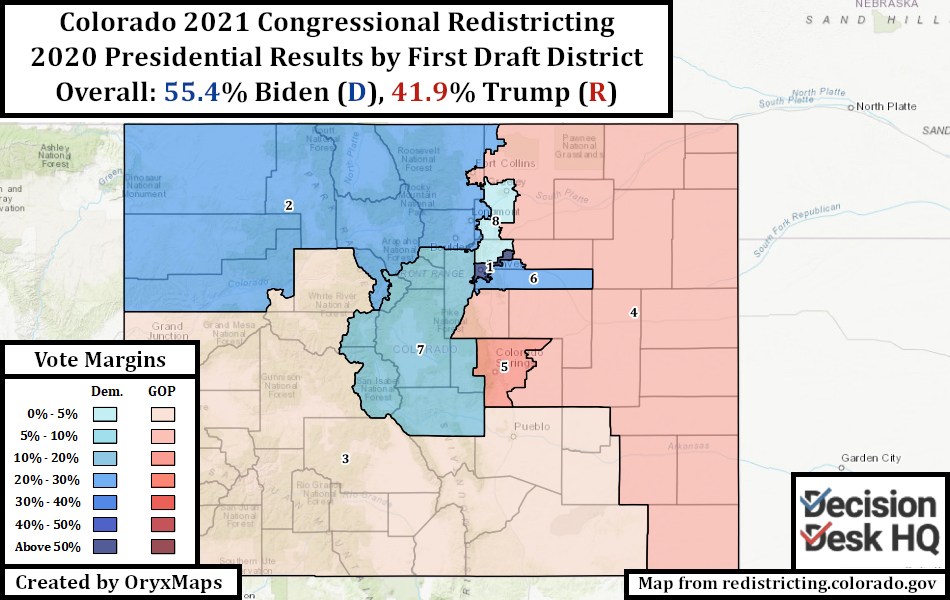

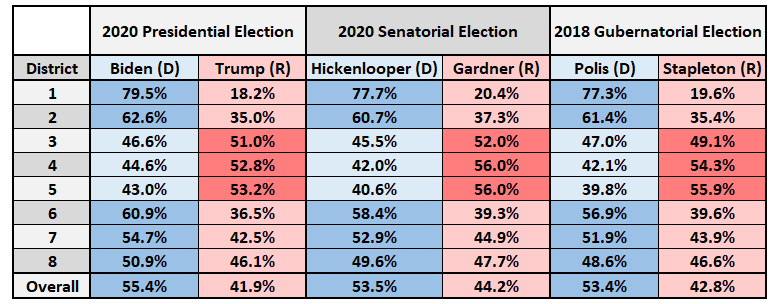

Colorado gained a Congressional district through reapportionment and now has eight seats. Colorado uses a multi-partisan citizen-led commission to draw the lines for these districts. This commission has held public discussion forums for several months to obtain citizen input. The commission previously released preliminary maps drawn using American Community Survey population estimates. The new Congressional map uses official Census population data.

This map differs drastically from the previous proposal. The only districts that resemble their previously proposed iterations are the First, Fifth, and Sixth, all districts anchored by large cities with clear community borders. The released map noticeably resembles a plan the Colorado Latino Leadership Advocacy and Research Organization proposed one day earlier, just with several edits to increase competitiveness.

In a departure from their previous plan, the commission now endorses a South Colorado seat built around the region’s Hispanic population. Drawing this district requires cuts across the Rocky Mountains and separates some Western Slope counties from their neighbors. Under the proposed lines, the separated counties get paired with the university community in overwhelmingly Democratic Boulder. This unusual decision is followed by another: putting urban Fort Collins in the eastern Fourth seat and joining it with South Denver suburbs by hundreds of miles of rural ranchland. Greeley, the large city directly to the east of Fort Collins, is however removed from the rural seat and paired with Denver’s northern suburbs. Cross-county cities such as Westminster that were united under the previous plan are now cut.

This map is unlikely to be final, especially given the litany of public comments already expressing disbelief at the Fort Collins decision. The commission begins the process of collecting public criticism on this map, and will draw a third proposal in the coming weeks. That future map will likely diverge significantly from this present proposal, just like how this proposal departed from the preliminary ACS map.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.