Many states released redistricting proposals this week, so Decision Desk HQ split our analysis in two articles. Our first analysis covered Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, Nebraska, and other lesser developments. Today’s article (re)examines states that initially focused on legislative lines or that released maps later in the week: Alaska, Colorado, Iowa, and Ohio.

Alaska

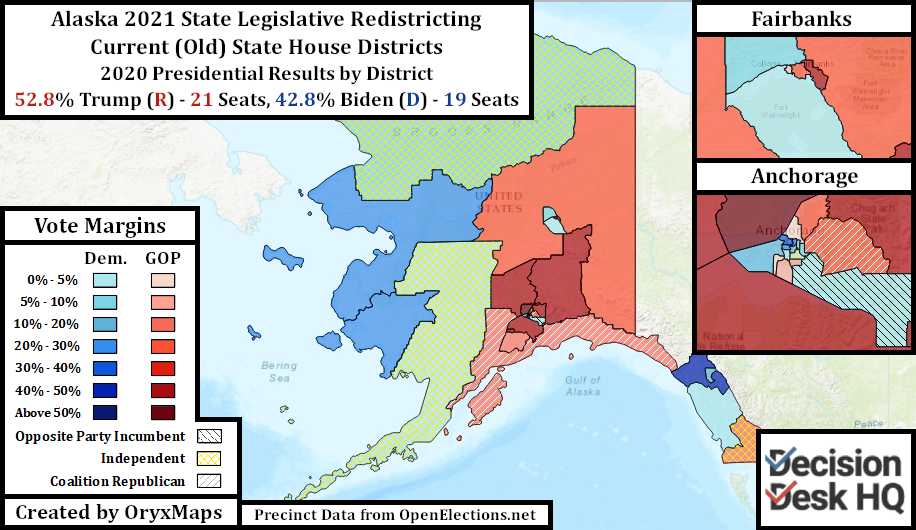

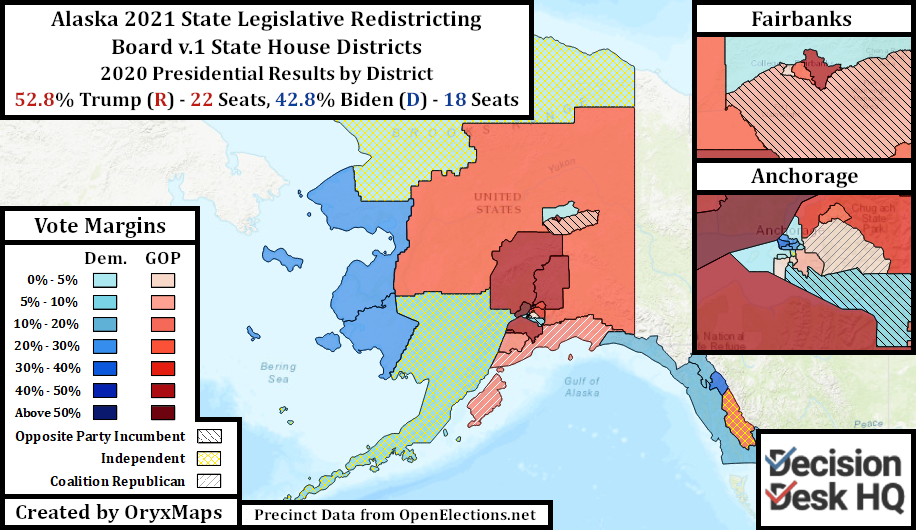

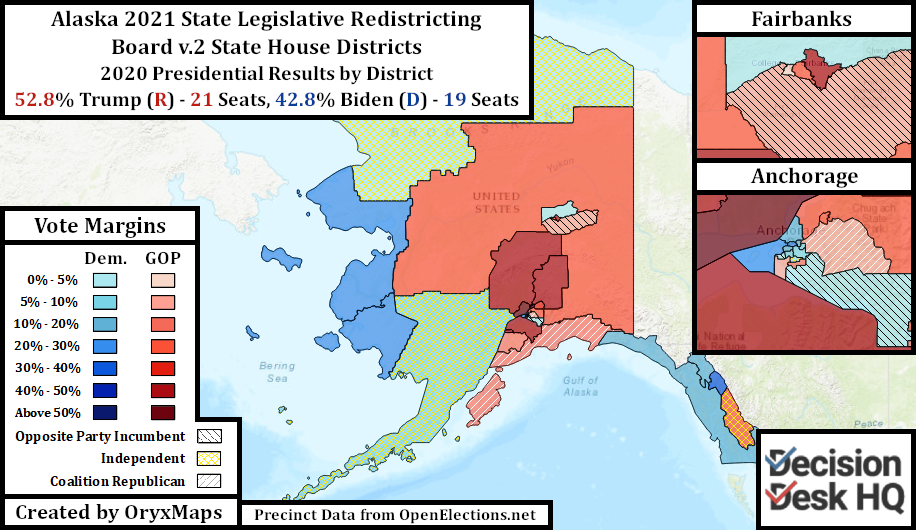

The Last Frontier has peculiar politics that complicate redistricting. Independents can win elections, even when a seat is considered safe for one party. Democrats “control” the State House through a coalition of elected Democrats, Independents, and cooperative Republicans. Alaskan voters approved a top-four ranked-choice voting initiative in 2020, increasing the potential for future coalitions and Independents.

Alaska redistricts using a five-member commission. Five citizen members are appointed: two by the Governor, one by the Alaskan Chief Justice, and one by each leader of a legislative chamber. Republican Governor Mike Dunleavy’s two appointees and the one from the Republican-controlled State Senate functionally gives the commission a Republican majority.

Alaska’s political geography favors the Democrats. Despite losing the state by 10%, Joe Biden almost won a majority of State House districts. Joe Biden’s narrow win in Anchorage and Republican voter concentration in the Mat-su Valley and the Kenai Peninsula produced this discrepancy.

Strict guidelines and native minority access laws prevent the commission’s Republican majority from passing a gerrymander and correcting for the geographic imbalance. Instead, the mappers shuffled Anchorage Coalition incumbents in plan v.1. The map pairs Coalition incumbent legislators in new districts and separates other incumbents from their bases of support.

The v.2 map only changes legislative districts within Anchorage and leaves the outlying districts from plan v.1 unchanged. The v.2 map largely maintains the current Anchorage district configuration, pairing fewer incumbents and protecting more. Both maps are however preliminary, and citizen forums will force changes to the districts before implementation.

Colorado

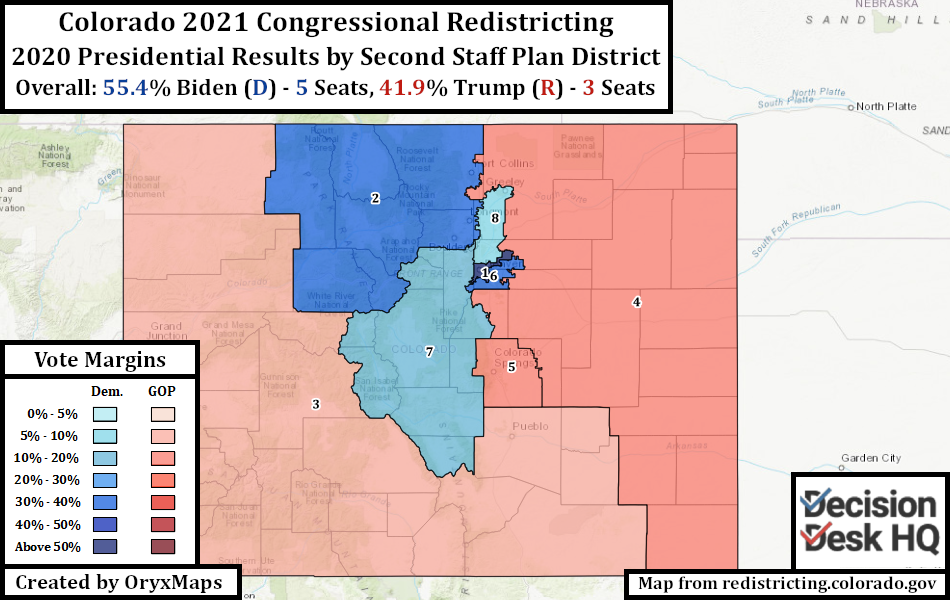

Colorado’s redistricting commission has already released numerous maps as part of its deliberation process. The commission initially published maps for each chamber built using American Community Survey data. Those three maps sparked discussion before the official release of Census data, which led to the commission’s first official Congressional plan – the First Staff Plan.

The commission found itself forced to immediately partially redraw the First Staff Plan after public backlash to that proposal. The Second Staff plan corrects the obvious faults of the first. Fort Collins rejoins the rest of Larimer County, although now neighboring Loveland is removed and put in the rural Fourth District. Colorado’s rural northwest corner reunites with the rest of the Western Slope, in exchange for the ski resort areas like Eagle County which are now in the Second District. The three Denver suburban districts traded some localities between each other.

The production of successive Congressional plans slowly revealed what the commission would refuse to accept. Their guiding principles appear to be: keep the city of Denver together in CO-01; maintain the unity of Aurora in CO-06; place CO-05 entirely inside El Paso County with the entirely of Colorado Springs; extend CO-08 north from the Denver suburbs into Weld County; and, Pueblo must remain with southern Colorado’s rural Hispanics.

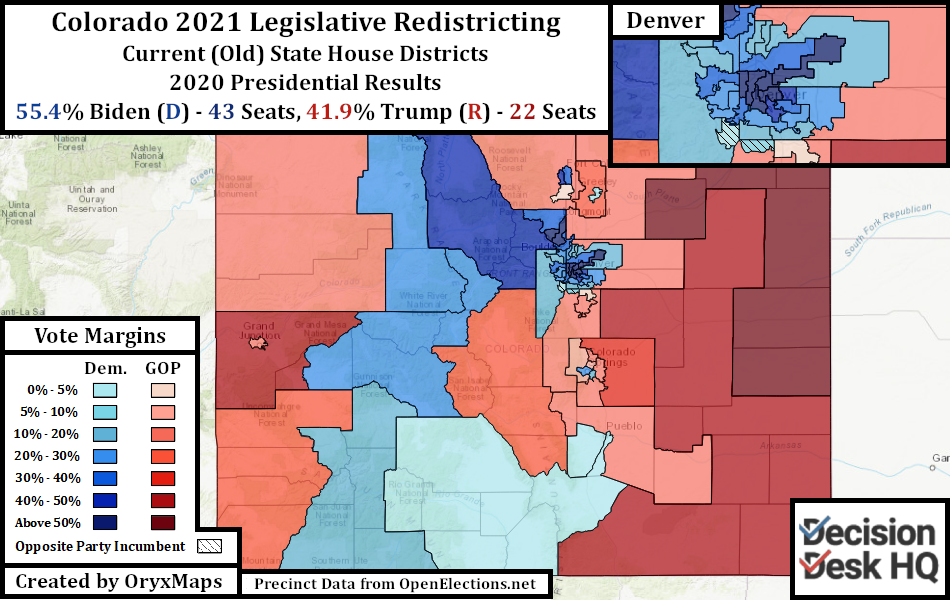

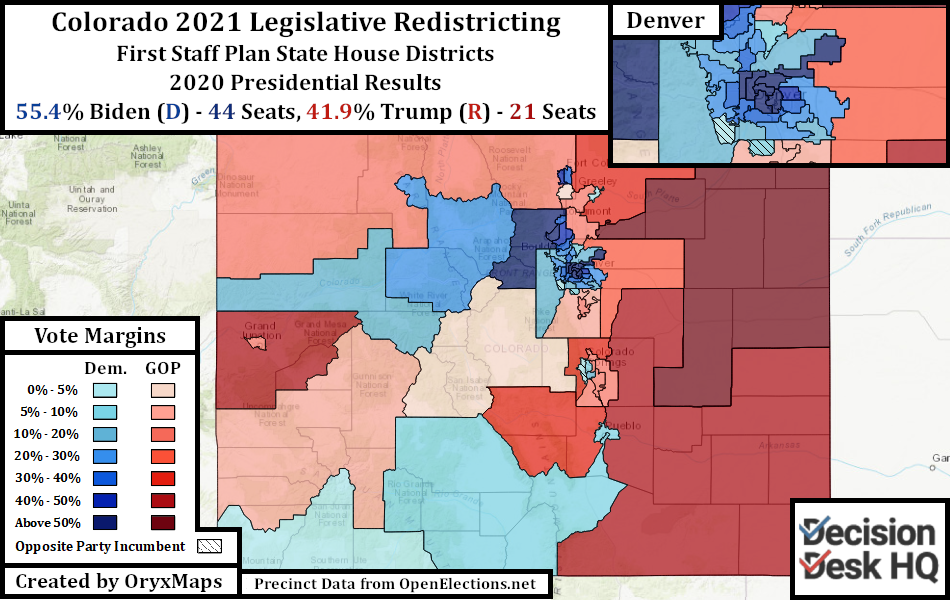

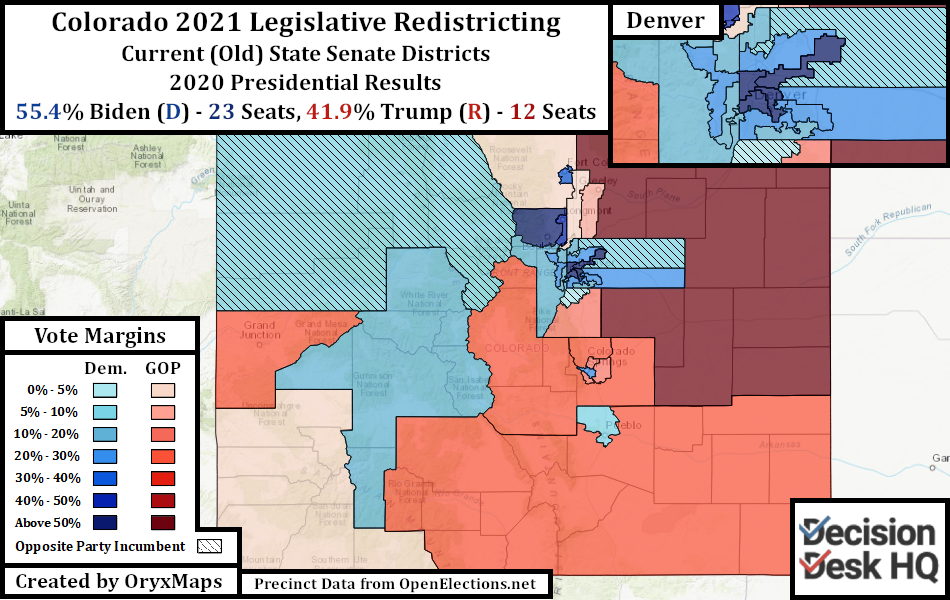

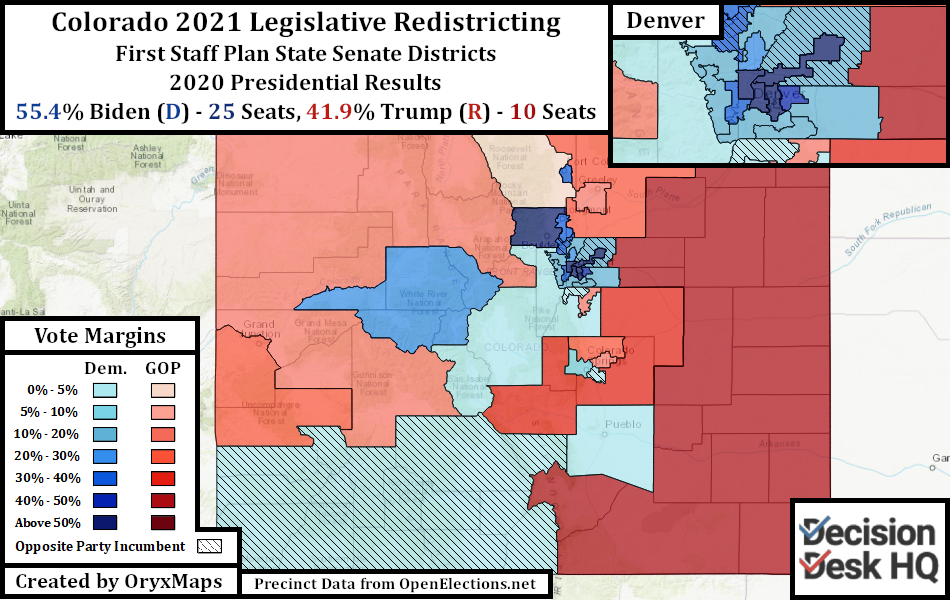

The First Staff Legislative proposals were however this week’s main release. Similar to the Congressional districts, this map’s lines try to follow locality and community boundaries. Districts are nested inside cities, even when those cities cross county lines.

The State Senate map proposes major changes when compared to those proposed for the State House. The only partisan difference between the previous and proposed State House map is a third Biden district in Colorado Springs. This change is one of many proposed on the State Senate map. The State Senate proposal redraws the northern Front Range and eliminates the three parallel State Senate districts going North-South from the Denver suburbs into Weld and Boulder Counties. The creation of compact districts guarantees two Democratic pickups in the north suburbs. However, it will be difficult for the Democrats to hold the proposed seat organized around the sprawling southwest Denver suburbs and Park County. Both proposed maps will likely see redraws, but neither should drastically change.

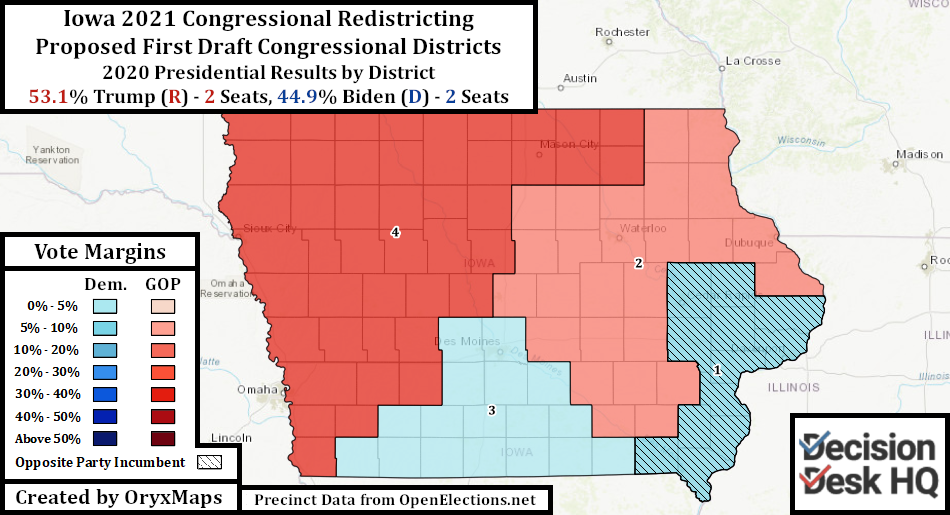

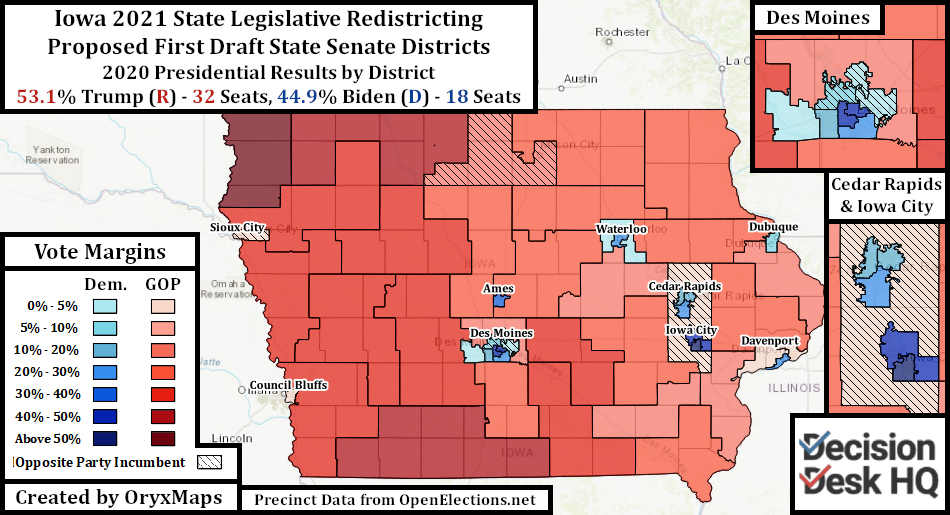

Iowa

Iowa redistricting follows a procedure unique among the fifty states. First, a commission of four non-politicians is appointed by the majority and minority leaders of both legislative chambers, with the group then selecting a fifth from among themselves. This commission uses computer algorithms to create compact and equivalent districts. The Congressional districts cannot cut any of Iowa’s 99 counties. The legislative algorithm creates groups of counties with the appropriate population for a specified number of districts with the purpose of preserving county integrity whenever possible. Next, legislative districts are drawn inside these county groups. These plans are finally submitted to the legislature as a single package for an up or down vote and a gubernatorial veto.

Republicans control the Iowa State House, the State Senate, and the Governor’s office. The GOP has total power over whether a proposed commission plan is approved. Rejection historically happens because the three maps are all part of one package. Faults in just one map, such as if legislative incumbents do not like their new districts, can sink a proposal. If a package is rejected, the legislature provides feedback on what it would agree to in the next proposal. If three packages of maps fail to pass then the legislature can implement its own plans with oversight from the State Supreme Court. This has never happened and every map since 1980 was drawn by the commission and its algorithms.

The GOP has many reasons for rejecting these initial maps. The Congressional map proposed by the commission shifts from four districts Trump won in 2020 – three of these by narrow margins – to a map where each presidential candidate won two seats. Despite Iowa’s recent migration towards the GOP, the state’s political geography still favors the Democrats. The fiercest Republican areas remain in the northwest corner of the state, whereas the Democratic vote is dispersed across the east and center of the state in small cities.

Republicans in 2000 directed the commission to correct this geographic imbalance, rejecting the first proposal. The 2010 congressional product retained these outlines and divided Iowa into four quadrants. It appears likely the legislature will once again reject the proposals – especially since the most Democratic district on the proposed plan is presently represented by freshman Republican Ashley Hinson.

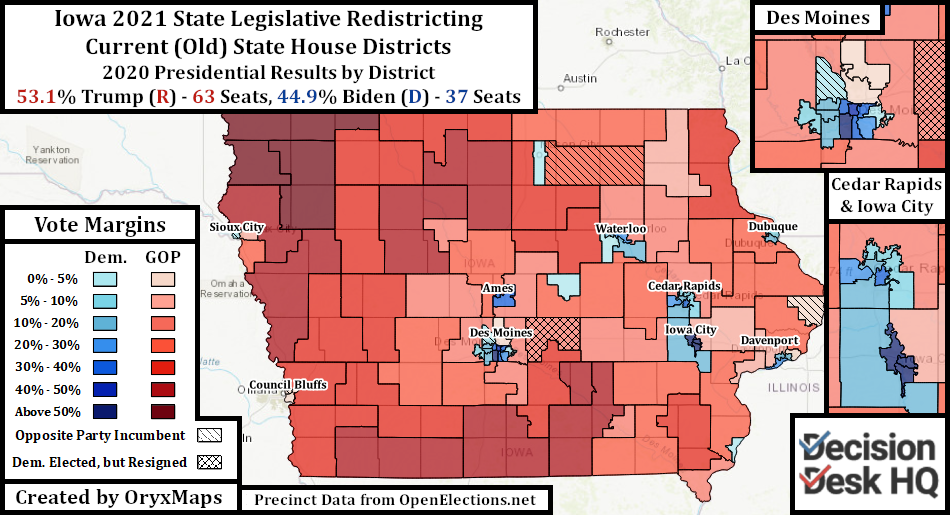

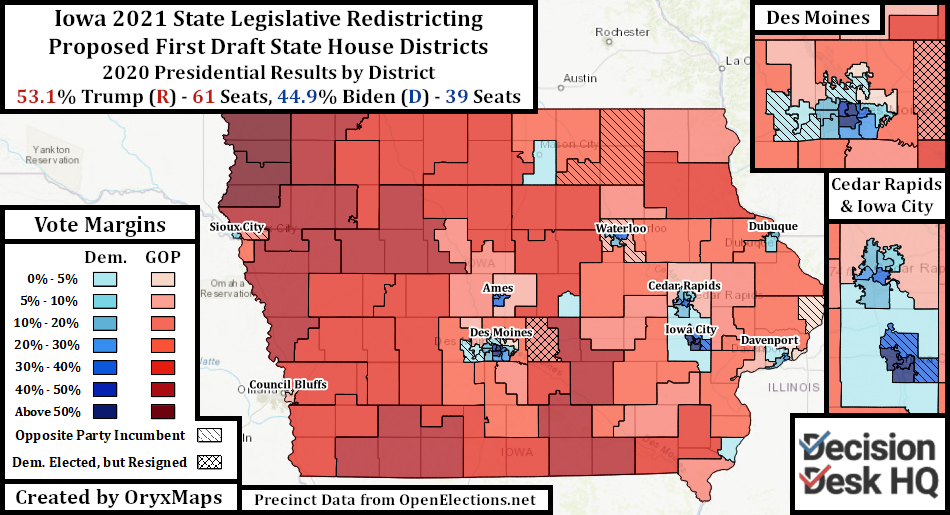

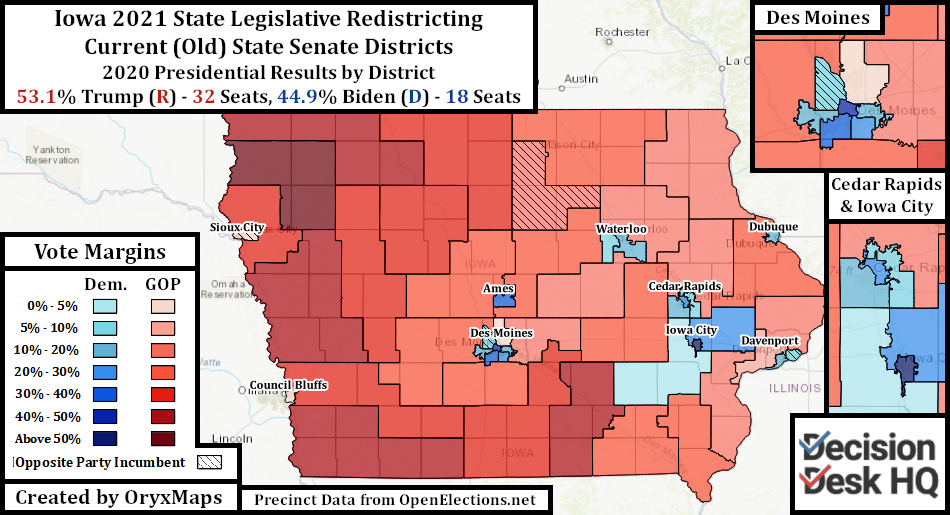

The legislative maps also may imperil the initially proposed package. These legislative proposals largely maintain the geographic alignment of the current districts in rural Republican areas, with the exception of those legislators whose districts migrated across the state through reapportionment. This is understandable since both the previous and the proposed map have to follow the same set of county and community guidelines.

These maps could net the GOP several seats in both chambers even though multiple districts were reapportioned from rural areas to growing Democratic cities and suburbs. This is because Democrats currently hold several Trump-won seats that become even more Republican and because some Democratic incumbents lost Democratic communities and would take in hostile ones. A handful of districts represented by Republican incumbents however undergo dramatic reorientations, and many incumbents residencies are now paired even though their districts remain geographically similar. These GOP incumbents could sink the current proposal.

If the legislature rejects the map package, the commission has 35 days to create a second while trying to follow the legislature’s recommendations. Some political observers speculate the GOP will reject the second and third plans in succession even if these plans conform to their wishes. The purpose would be to seize power from the commission and draw gerrymanders they desire. This would be a significant and unpopular rupture with precedent. It seems unlikely that the legislature will reject subsequent commission plans that satisfy their immediate concerns.

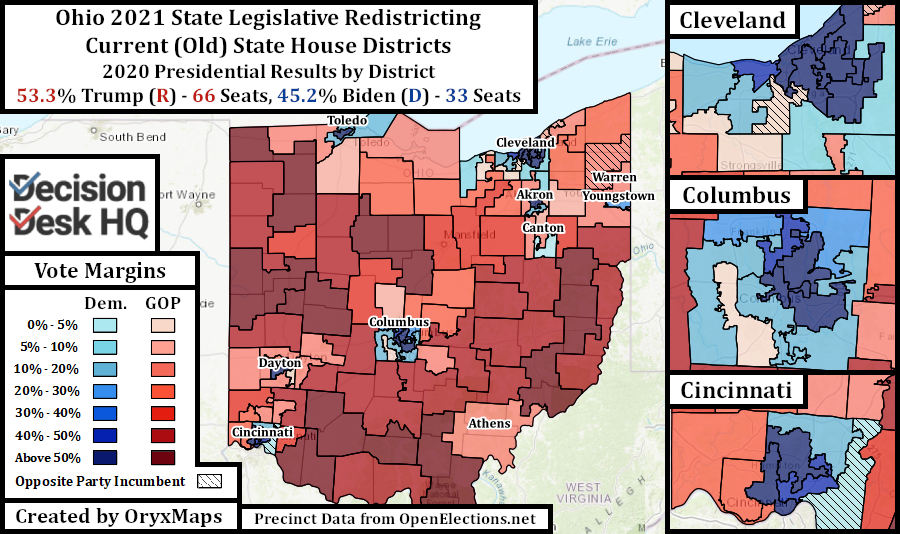

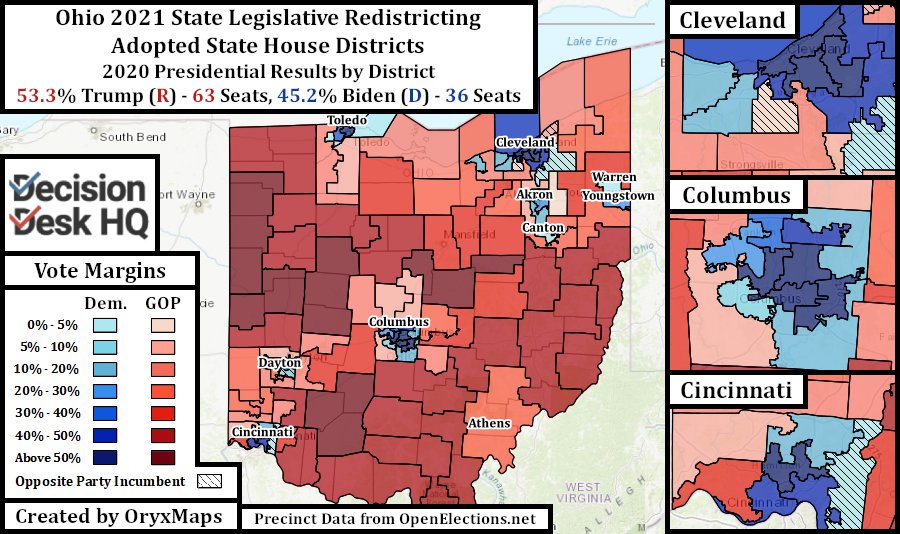

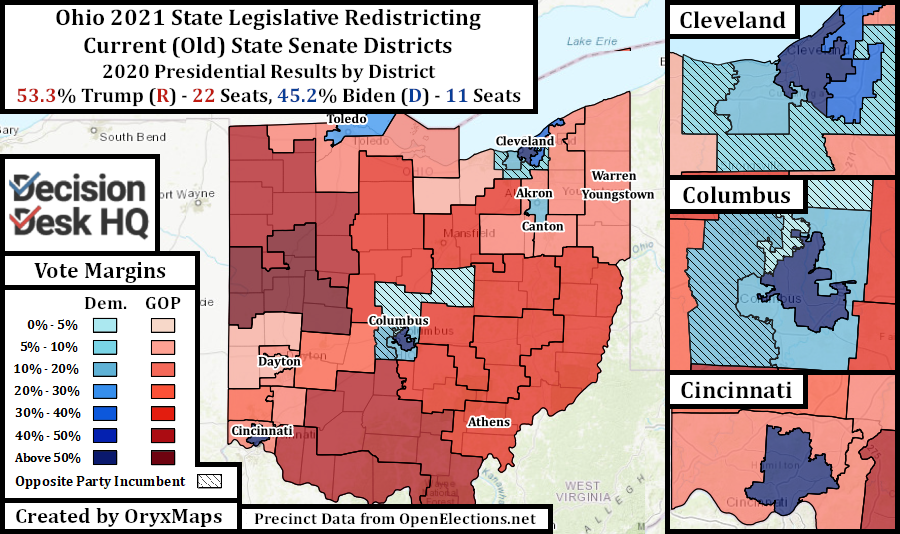

Ohio

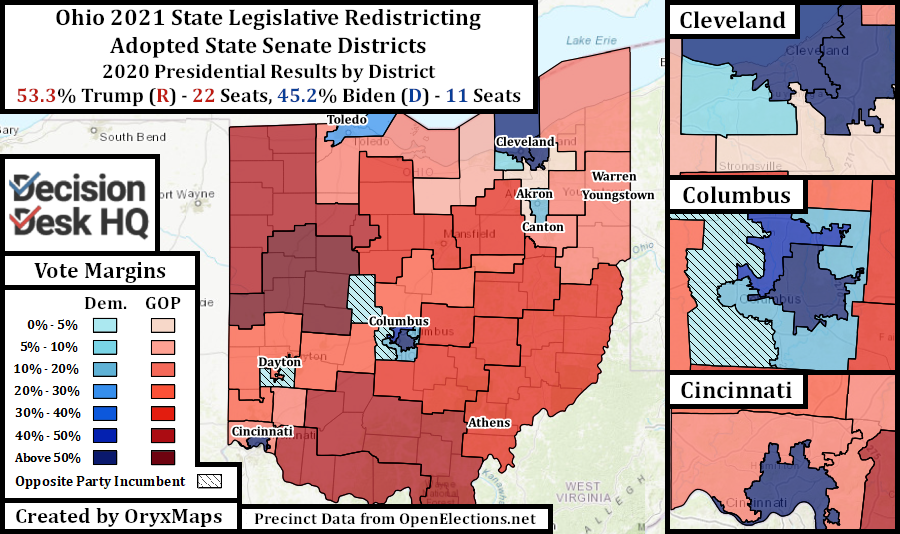

Ohio voters approved redistricting reform in 2018. The reform created a seven-member appointed commission, but with weaker powers than those in other states. Three members are statewide officers – the Governor, Auditor, and Secretary of State – and four are appointed by the majority and minority leaders of both legislative chambers. New criteria for districts required seats hopefully follow community lines. The new law erected several hurdles designed to ensure that both parties agree to whichever maps are proposed, with an emergency backstop if no agreement is reached. If the parties cannot agree on a map, a simple majority of commissioners can approve a plan without support from the other party, but these maps would only remain in place for four years after which the redistricting process begins again.

The Buckeye State has a significant Republican geographic advantage. Similar to neighboring Indiana, analyzed by Decision Desk yesterday, Republican voters are efficiently distributed across the state in a way that allows the party to maintain continuous control over government.

Despite the potential for a fair yet Republican-dominated map, GOP legislators quickly moved to implement legislative gerrymanders. By ignoring all of the commission’s hurdles and proceeding to the four-year backstop, Republicans could propose lines similar to the previous decade’s gerrymanders. This blatant disregard for the new redistricting process did not go unnoticed; citizens denounced the commission’s product during a Dayton public panel held the week between the unveiling and passage of these maps.

To prevent Republican-held districts from dramatically changing, the implemented maps have near-illegal levels of population deviation. Rural seats are underpopulated and the growing cities and suburban seats are overpopulated. Only a single district in each chamber migrated into booming Columbus through reapportionment.

These legislative maps might not even survive. Ohio’s State Supreme Court has an anti-gerrymandering majority because of Republican Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor’s known opposition to the practice. With three fellow Republicans and three fellow Democrats, O’Conner has the power to strike down gerrymanders from either party. These maps seemingly violate much of the commission’s rules which are enshrined in Ohio’s constitution. The commission also rushed to complete its work with limited public input, though this was partially caused by a tight deadline. Republican Governor Mike DeWine and Republican Secretary of State Frank Larose lamented that the process should have been more open and “constitutional” after approving these maps, suggesting doubt over whether the commissioners followed their self-imposed rules. Decision Desk HQ will cover future, court-imposed remaps, if they occur.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.