The nationwide redistricting process accelerated this past week with more than ten states releasing provisional maps or redistricting materials. Decision Desk Headquarters split our analysis into two parts: the states that included Congressional districts in their proposals at the time of writing and the states that focused on legislative lines.

Arkansas

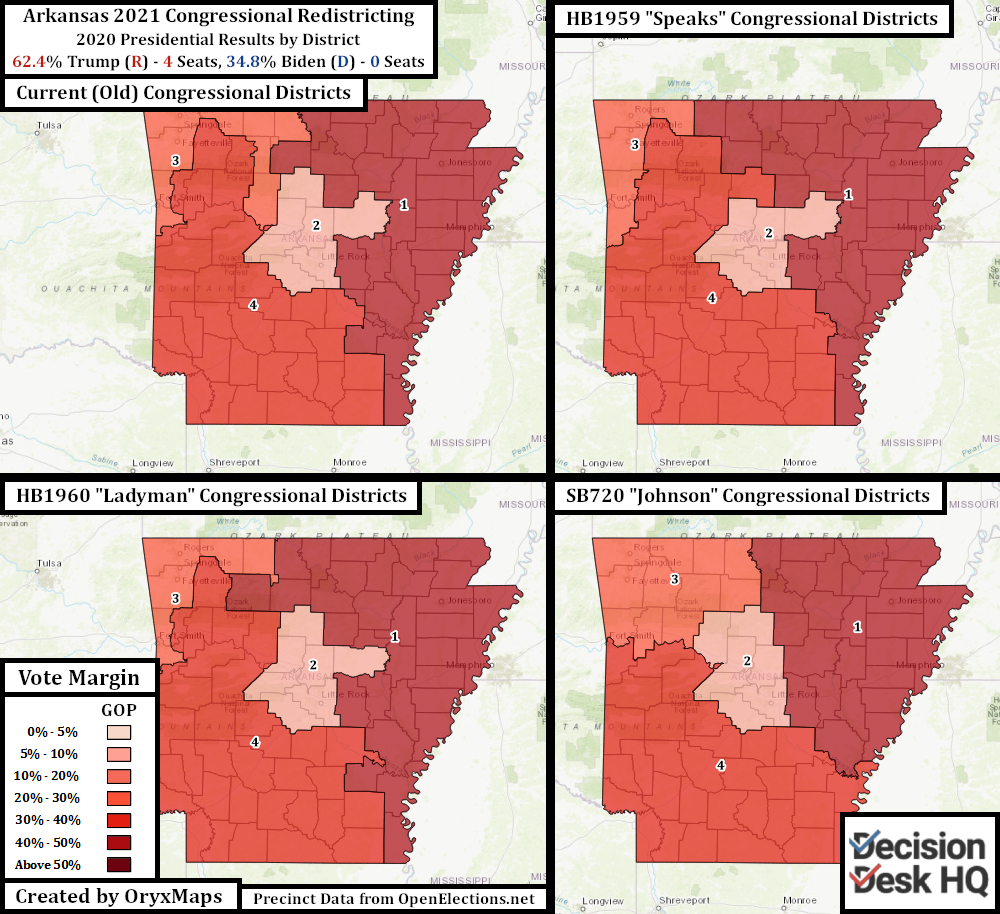

Arkansas is an overwhelmingly Republican state. All four of the state’s Congressional districts are represented by Republicans. Redistricting is the purview of the Arkansas state government. The Congressional redistricting process began last week when State Legislators began to submit bills for committee discussion. These three plans are designated by their authors: State Representative Jack Ladyman, State Representative Nelda Speaks, and State Senator Mark Johnson. More legislators will put forward more plans in the coming weeks, but it these three proposals give an idea of the desired outcome.

Rural White Democrats controlled Arkansas’s redistricting process in 2010, and they drew a Congressional district map that could elect three White Democrats, even though Obama lost all four implemented seats. This plan failed. Democrat support across the rural South continued to precipitously collapse, especially in Arkansas.

Arkansas elected four Republicans to Congress in 2012. The four Incumbents are today entrenched in their seats and want to preserve their current districts and maintain their current constituents. All three proposed maps make only minor adjustments to the four Congressional seats. This includes Republican French Hill’s Little Rock-based Second District, which saw two competitive challenges from Democrats in 2018 and 2020. All three maps actually make AR-02 less Republican than its current alignment, but only by about 1%.

Idaho

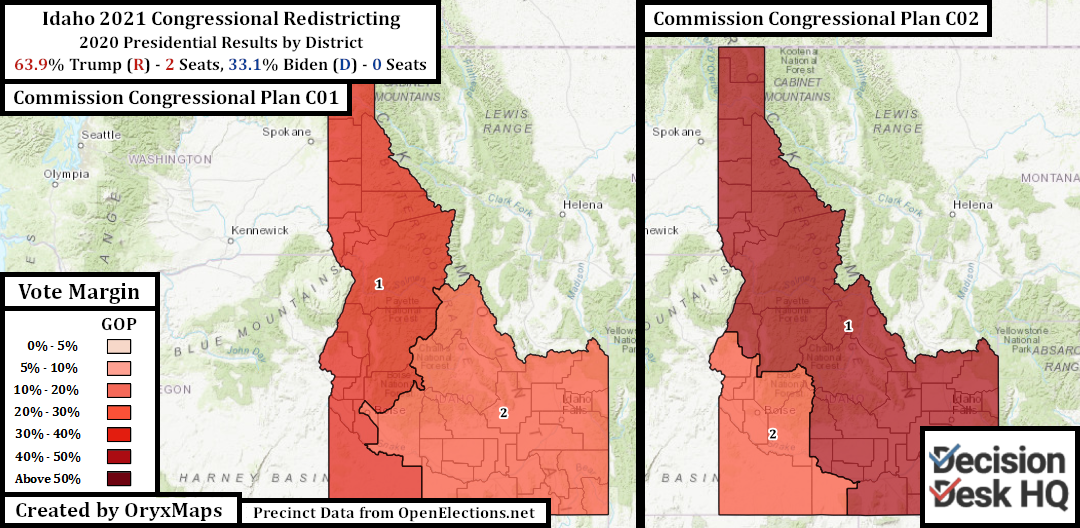

Idaho state maps are drawn by a multi-partisan commission. Party heads and legislative leaders in both chambers each select commissioners, dividing the body between three Republicans and three Democrats. Four (of the six) votes are needed to pass a map.

This commission has little impact congressionally. Idaho has had two Congressional districts since 1910, and the GOP has a partisan advantage in both seats. One district is in the west, one is in the east, and the two cut Ada County (Boise) along city lines. Every ten years a few Ada County precincts shuffle between the two seats to maintain population equity.

Despite the division of the state’s largest metro area, the alignment works because the two halves of the state are distinct. The east is Mormon and resembles Utah, the west is in a different time zone and has an outlook closer to the rural Pacific Northwest. It is therefore surprising that the commission released two potential Congressional plans: one that maintains the current divide and one that creates a Boise area seat. The seat that joins the east to Idaho’s panhandle is not even fully contiguous – mountains separate the two regions with no road inside the district connecting the two. Idaho will likely go with a map similar to Plan C01 presented above. Boise will need to wait another decade for Idaho to get a third Congressional district through a future reapportionment.

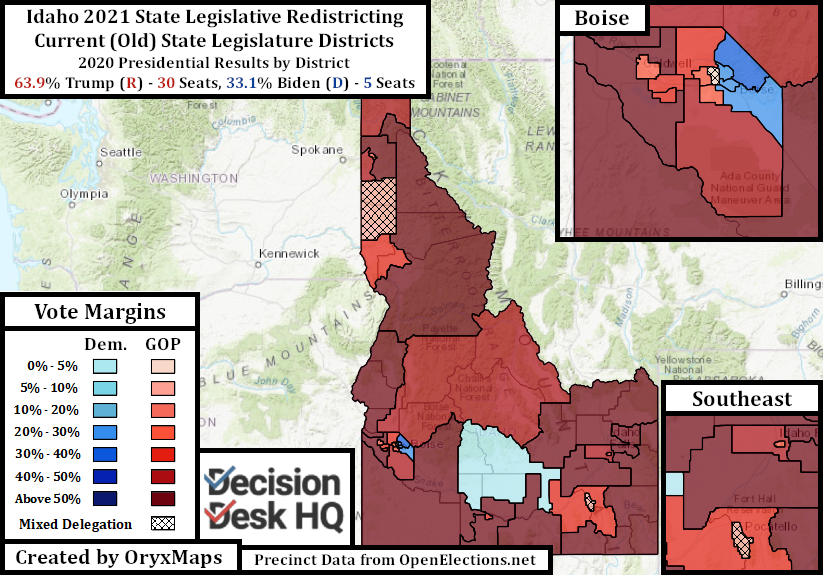

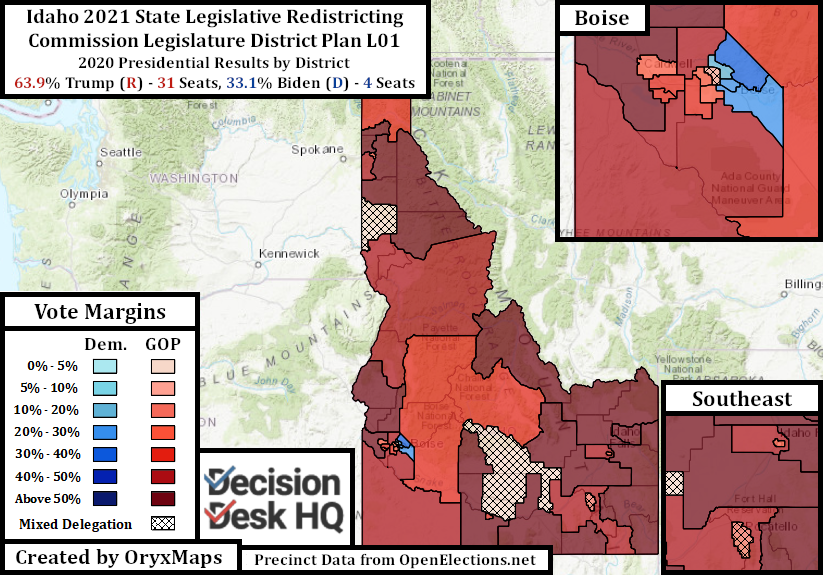

Idaho has one map with 35 seats for both of its legislative chambers. Voters elect two State Representatives and one State Senator to each district every two years. Voters can – and in some seats do – split their tickets to elect candidates from both parties on the same ballot. Idaho’s overwhelming Republican lean means Democrats are permanently in a minority; there is no need to gerrymander. Instead, districts follow community lines and try to maintain their shape from the previous cycle.

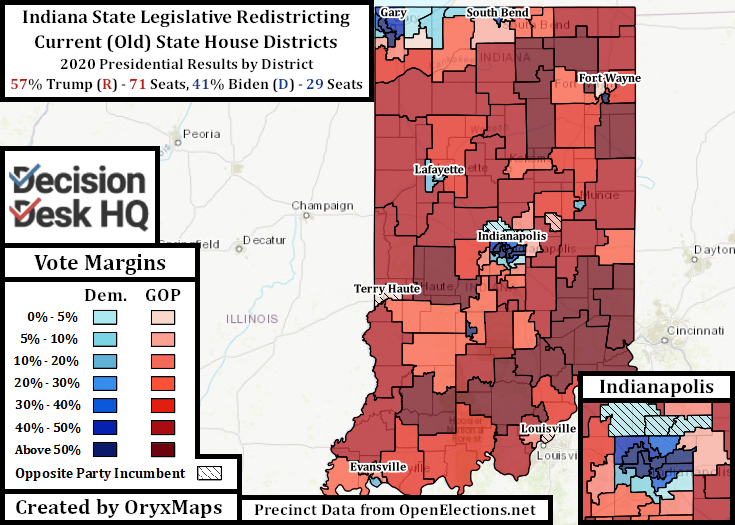

Indiana

Indiana Republicans have a significant geographic advantage. A geographic advantage is when one party’s voters reside in a distribution more efficient than the partisan topline would suggest. Imagine three counties with equal voters, and three districts must be drawn. Two counties have six voters from party A and four from party B, and one county has seven from Party B and three from party A. Drawing natural districts would give party A more seats, even though there is no gerrymandering. This is a geographic advantage.

Geographic advantage is falsely assumed to only benefit the GOP because crucial general election battleground states such as Michigan and Wisconsin have Republican-favoring geographic distributions. However, both parties benefit from geographic advantages in different parts of the country. Geography doesn’t always benefit the state’s dominant party; a party could lose a state 70-30 but win 40% of the seats if the dominant party’s voters are concentrated in safe seats.

Indiana Republicans swept the 2010 legislative elections. The GOP flipped two Congressional districts and won 60 State House seats after ten years of tight results and occasional Democratic majorities. The Republican party was eager to lock down these gains and prevent a resurgence from smalltown Democrats. They drew a brazen legislative gerrymander and cemented Congressional control with neat yet partisan lines.

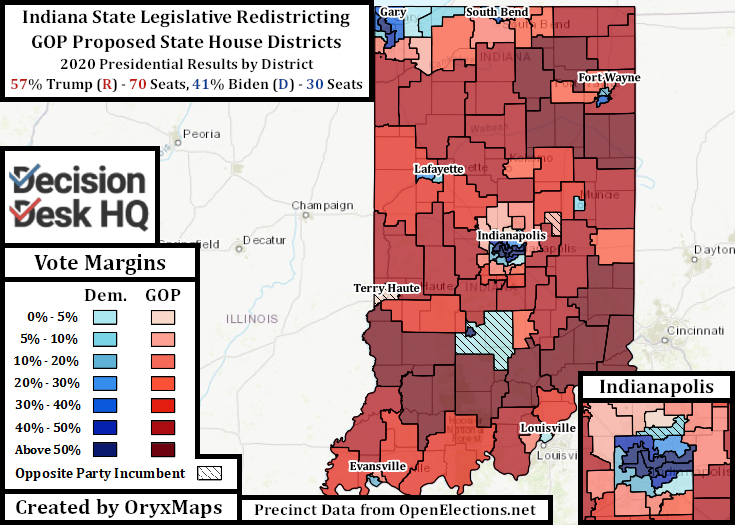

Indiana Democrats have remained in obscurity since 2010. In retrospect, Indiana Republicans did not need their 2010 gerrymander. Geography locked in their majority. The legislators in 2020 therefore undid most – but not all – of the previous map’s oddities and gave incumbents community-oriented districts that are easily serviceable. These potential changes at times benefit Democrats. For example, the 2010 map sliced Fort Wayne into pieces and paired the pieces with the surrounding counties; now there are compact districts and a second Democratic house seat inside the city.

Republicans did not completely undo their gerrymanders. There were previously three Biden-won seats in the Hamilton County suburbs directly to the north of Indianapolis – including Republican Speaker of the House Todd Huston’s district – and now all three contain outlying GOP exurbs further north. These changes immediately benefit Republicans, but it was not possible to draw these districts without compensating the opposition. The proposal creates a new, reapportioned, Democratic seat using Hamilton County precincts in Carmel and Fishers.

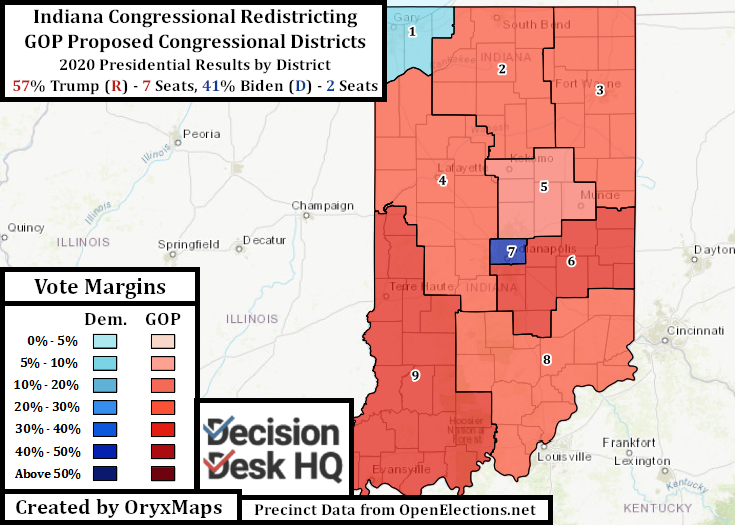

The Congressional plan is similarly neat and Republican-favoring. Republican mappers could have gone after Democrat Frank Mrvan’s First District, as they had sufficient voters. However, it appears no incumbent wanted to take in more Democratic voters, including the city of Gary. The proposed plan therefore maintains the bases of the current districts with the most drastic changes occurring in the southeast. The Democratic Indianapolis-based Seventh seat swaps voters in the south of the city for those in the north. The south city neighborhoods resemble their suburban Republican neighbors, whereas voters in the north flipped Democratic so fast they endangered Republican control in their former Fifth district. These changes protect Fifth District Republican incumbent Victoria Spartz, and make the new IN-07 less than 50% White. The Sixth and the Eighth (previously the Ninth) Districts are now redrawn East-West, rather than North-South, to better align with the bases of their Republican incumbents.

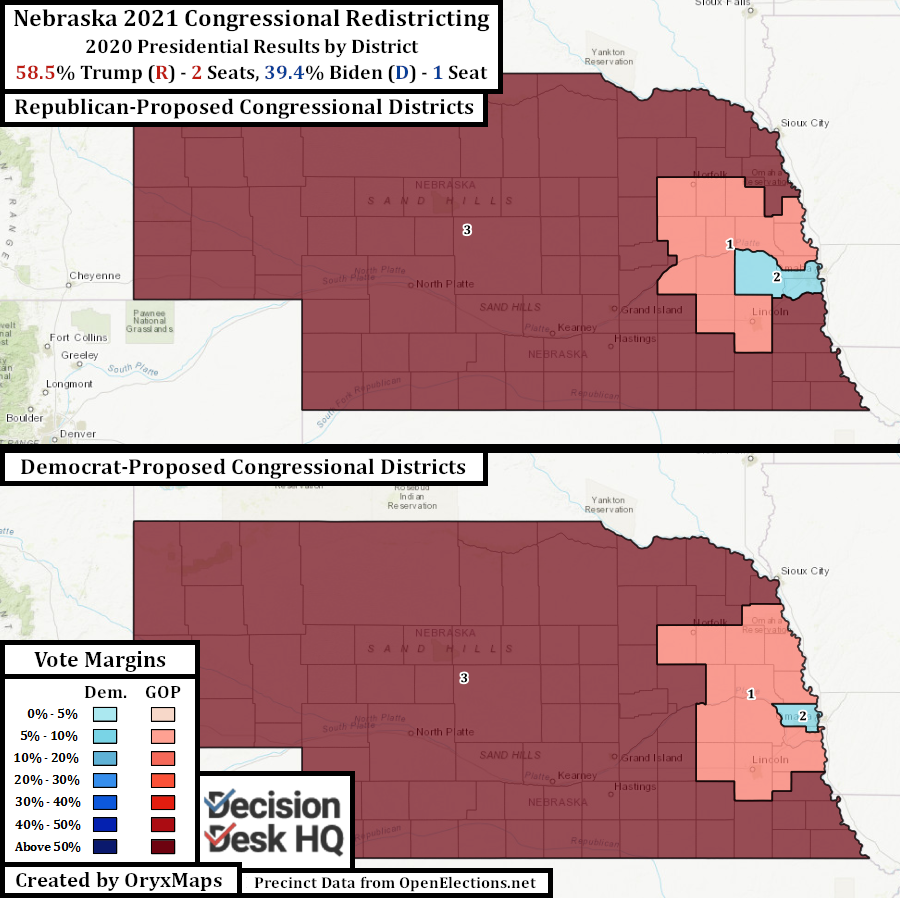

Nebraska

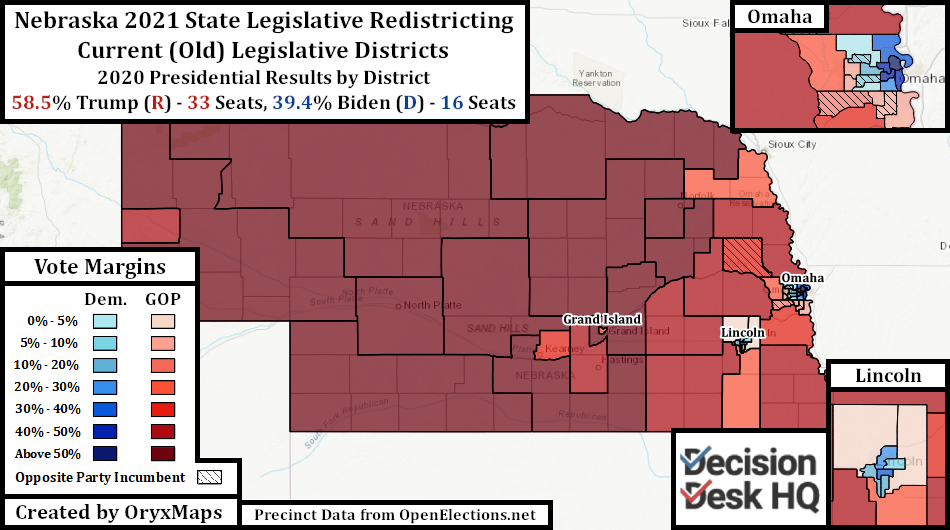

Nebraska is the only state in the country with a unicameral legislature. Those elected to this chamber do not have an official party registration, though this is merely a formality inside the chamber. This provision however occasionally allows self-identifying Democrats or Republicans to win seats where their presidential candidate was uncompetitive. Nebraska is one of two states to allocate its electoral college votes by Congressional district. Voters in the Omaha-based Second District gave Biden their electoral vote by a 6.6% margin in 2020 but also reelected their Republican incumbent, Don Bacon.

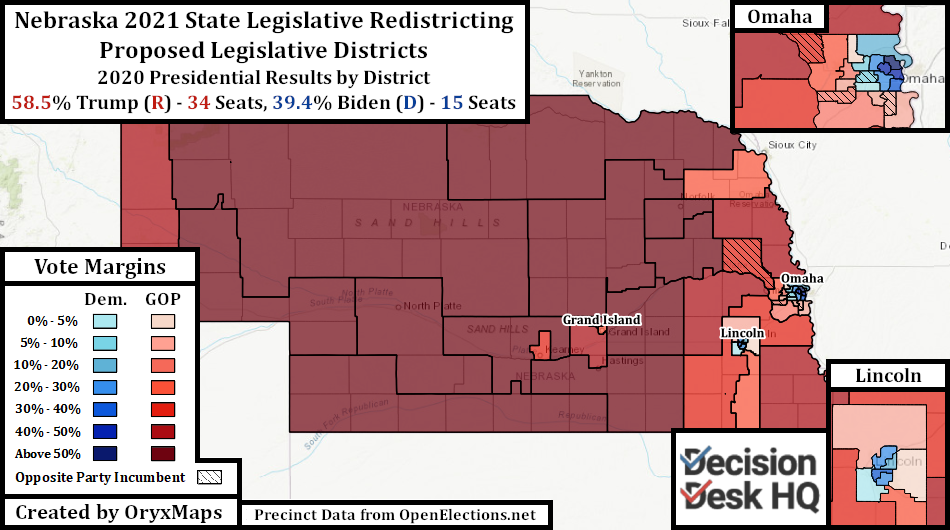

Republican-identifying legislators have multiple incentives to gerrymander NE-02, but they appear to have not. The map they proposed is more Republican than the current plan, but only by 0.6%. It traded about 140K voters in the most Republican parts of Douglas County (Omaha) for parts of neighboring Sarpy and Saunders Counties with a similar partisan distribution. Democrats are unlikely to get their proposed map passed – which realligns NE-02 into a seat Biden won by 9% – but the plan is shown here because of tradition. Douglas County has never been cut during redistricting, and even though the proposed cut leaves Omaha mostly intact, map negotiators may find that simply cutting the county may produce too much outcry.

The State Legislative lines are better examples of gerrymandering. Republican-identifying legislators stated that they were proud that only one district moves from the shrinking rural counties into the cities, preserving current constituencies and incumbents. To achieve this outcome, urban districts are overpopulated – but not to a degree that would run afoul of Nebraska law – and rural districts are underpopulated. Urban Republican districts are reconfigured and shed Democratic precincts to protect their incumbents.

Miscellaneous Proposals

The following states released redistricting proposals this week but are not covered in either of these articles. These states will be covered at a future date when the maps become finalized or those with the actual power in the process pick up the pen. These states are:

Arizona: Arizona’s Independent commission released its grid maps. The commission uses these maps as the starting point of discussion for future alignments. This is because the commission is required to ignore all previous district maps, which would in other states fulfill the role of the grid maps. These new maps do not follow any voting rights laws or community groupings. Their purpose is to identify the areas the commission wants to make the geographic core of each seat. For comparison’s sake, these were the 2010 grid maps compared to the final 2010 Congressional product.

Maryland: The Maryland Citizens Redistricting Commission released its preliminary Congressional proposal. This plan erases the previous map’s gerrymandering and creates districts built out of county groupings. The Maryland proposal however has population equity and minority access problems. This commission is toothless and is unlikely to implement its plan. Republican Governor Larry Hogan created the commission through executive fiat by and its plans must be approved by the Democratic legislative supermajorities. Legislative Democrats can override Hogan’s veto and are likely to ignore this commission in favor of their own gerrymanders.

New York: New York’s has a redistricting commission, but in this instance it is powerless. On September 15 the commission further weakened its authority by releasing two competing proposals: one drawn by the Democrats and one by the Republicans. Both are gerrymanders. The commission’s final proposals can be accepted or rejected by legislative supermajorities, and Democrats have the votes in both chambers. These maps are therefore hypothetical; those involved in New York redistricting know the Democratic legislature intends to use its veto to ignore the commission and draw its own maps. The Legislative takeover however can only be done after the commission completes its legal obligations to deliver maps for summary rejection.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.