Latin American democracy has never lived up to its ideals and values. Two months ago, Decision Desk Headquarters analyzed the unfortunate Latin American political undercurrents of corruption, political fragmentation, “Caudillo” politicians, and wide wealth gaps. We analyzed the Ecuadorian Presidential runoff, the first round of the Peruvian Presidential Election, and the then upcoming Chilean Constitutional Election. A common theme in these elections was the conflict between the electorate’s desire to shed the corruption of the current system and said political system’s resistance to any reform. Two more Latin American elections this week exhibited this tension.

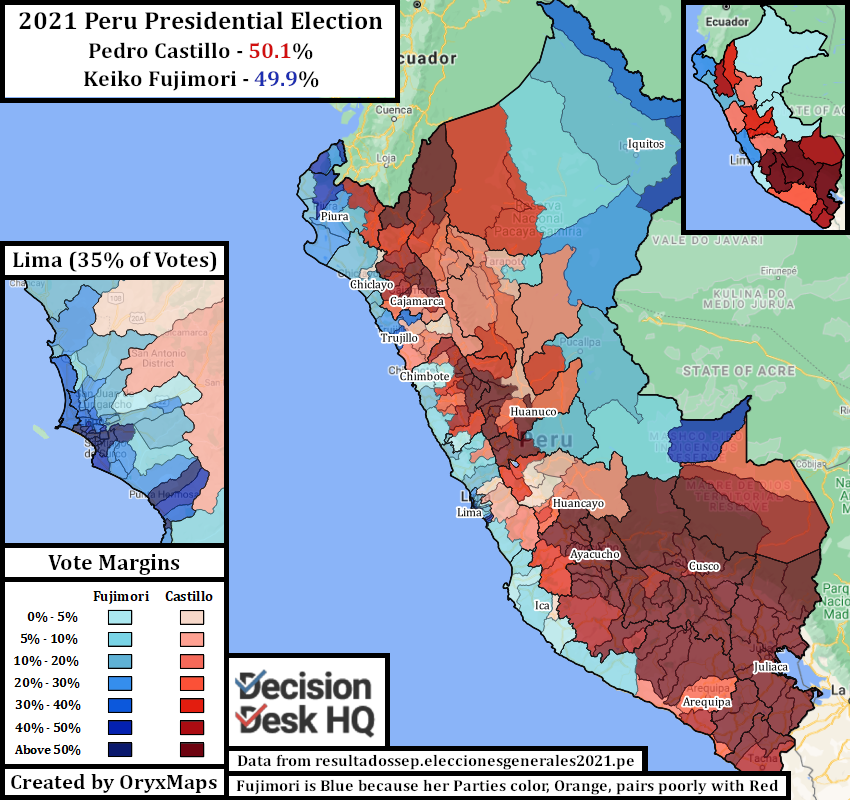

Constant corruption and political paralysis have destroyed Peruvians’ faith in democracy. A record number of candidates ran for the Presidency promising change. The two who promised extreme change advanced to the June 6 runoff. Keiko Fujimori campaigned on a platform of restoring the stability of her father President Alberto Fujimori’s authoritarian rule in the 1990s. Her rival Pedro Castillo sought a constitutional overhaul and socialist transformation of Peruvian society. For many Peruvians the choice was between a “lesser of two evils,” but this did not demotivate the polarized electorate. It clear that Castillo will defeat Fujimori by a narrow margin around 0.2 percent.

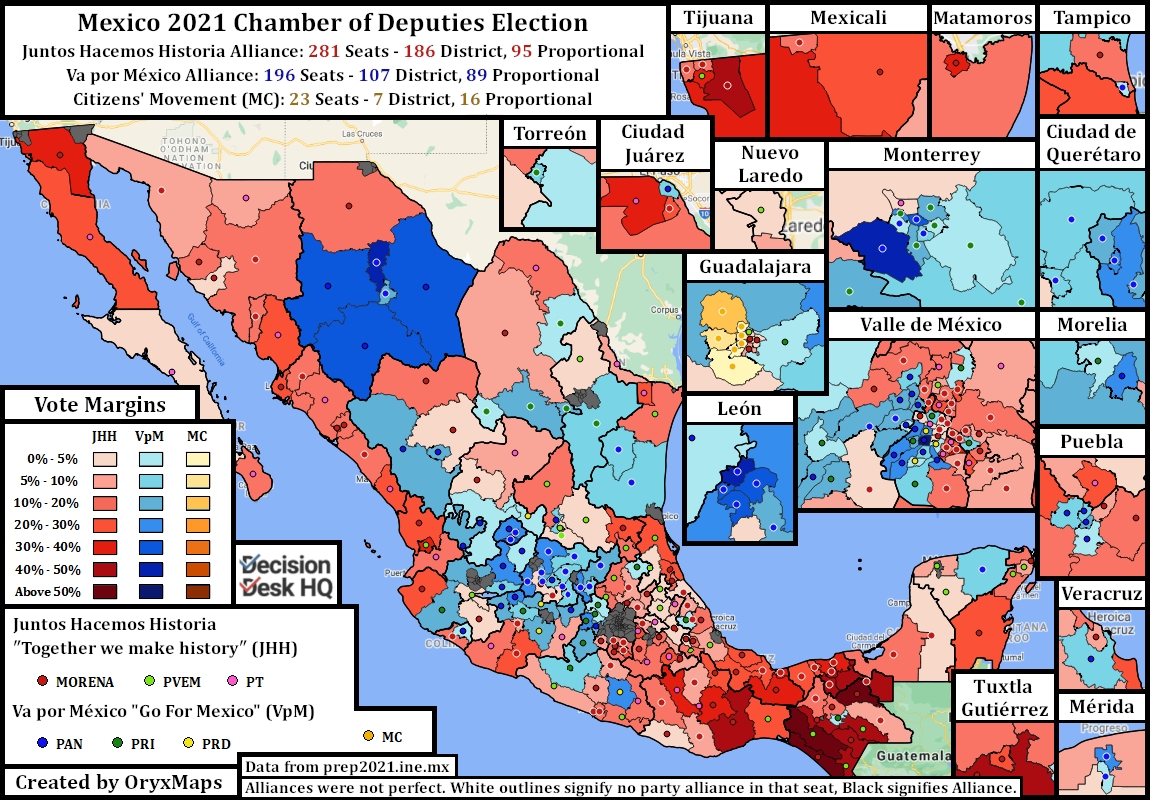

Mexico also held its midterm elections on Sunday June 6. On the ballot were Governors for fifteen of Mexico’s 32 federal bodies (31 States and the Capital district), countless local and mayoral offices, and all 500 seats – 300 constituencies and 200 proportional – in Mexico’s Chamber of Deputies. This election is a referendum on incumbent President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (henceforward referred to as his nickname, AMLO) and his reformist movement that swept the 2018 elections. Opposing AMLO’s MORENA party and its minor allies is an alliance of Mexico’s traditional parties: the PVI, PAN, and PRD. Despite idealistic messaging, both alliances feature corrupt candidates with shady pasts who engage in illiberal tactics to win their elections. The results were a mixed picture. MORENA and allies lost congressional seats to the opposition alliance, but won 12 of the 15 gubernatorial offices.

Voters also demonstrated their desire to break free of an ineffective political system last month in Chile. The traditional Chilean Right failed to win the one-third of the seats needed to veto any changes at the constitutional convention, but the beneficiaries of this poor showing were not Chile’s traditional Socialist or alternative Left alliances. Instead, large numbers of independents, regionalists, and lists tied to the 2019 grassroots protests won election to the convention.

Ecuador’s legislative politicians additionally have solidified the desire for change. A surprising Conservative-Indigenous political alliance formed in the wake of April’s Presidential election. This alliance stopped Correra’s allies from controlling the National Assembly.

Peru

Peruvians want a way out of their national crisis. Peruvians suffer daily from widespread political corruption and the nation’s failed coronavirus response. Every presidential candidate tailored their platform to try and solve the crisis. In spite of this desire, the first round vote delivered a fragmented result. The two candidates who advanced, Keiko Fujimori and Pedro Castillo, promised drastic change and appealed to Peru’s growing dissatisfaction with democracy, albeit in opposing and mutually incompatible ways.

Castillo, a rural teacher with past ties to the Marxist terrorist group Shining Path came in first place with 18.9%. Keiko Fujimori, the unpopular daughter of controversial authoritarian former President Alberto Fujimori, won the second runoff slot with 13.4%. Each candidate complimented the other’s campaign. Fujimori promised a return to her father’s “Fujishock” economic boom and a strong hand against crime and insurgents. Castillo proposed a socialist transformation that would lift up the impoverished rural and indigenous areas. Keiko Fujimori promised to pardon her father, Castillo promised a new constitution to remake Peruvian political culture.

Castillo quickly consolidated support among rural voters who voted for other ‘transformative’ candidates in the first round. Fujimori initially struggled to overcome her unpopularity with the urban and free market side of the first-round electorate. On May 25th a peripheralized Shining Path splinter group Shining Path murdered 16 people and left political pamphlets warning against voting in the upcoming election. This act boosted Fujimori’s runoff campaign and helped her consolidate votes as the potential “lesser of two evils.”

The vote was very close, but Castillo has won. The final margin will likely be a Castillo lead between 40K and 50K votes out of over 17.6 million valid votes cast. This is the third time Keiko Fujimori has lost the presidential race by a narrow margin. Pre-election polls suggested that ten to fifteen percent of the first-round electorate would cast blank votes and reject the polarizing contest. Instead, polarization increased turnout and decreased the number of blank votes compared to round one. Fujimori did very well in urban coastal areas. This was especially true in the capital Lima, home to 35% of Peruvian voters. Castillo dominated the interior hinterlands. He swept the southern indigenous areas, winning some provinces with over 90% of the vote.

Castillo proposes radical change. It is not yet clear how he will implement this vision and how it will affect the nation. Castillo desires greater state participation in the economy and seeks to restrain foreign corporate extraction. He desires a constitutional convention to draft and replace the current constitution. Castillo is also a social traditionalist. He opposes gay marriage and abortion, wants to reinstate the death penalty, and supports stricter controls on the media. Nearly all these policies however must pass Peru’s Congress, and there is no natural majority for Castillo and his potential allies. It is entirely possible that the congress quickly impeaches and removes Castillo, just like his predecessors. Castillo though now wields the power of the bully pulpit, and may find ways to coerce the legislature to his will.

Mexico

Three parties were once at the center of modern post-Authoritarian Mexican politics. The first of these parties is the former party of the 20th century dictatorship, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). The other two parties only gained relevance towards the end of the PRI dictatorship, when a culture of corruption and clamor for democratic change tainted the PRI’s brand of stability. These are the pro-Business and individualist National Action Party (PAN), and the Social-Democratic PRI splinter Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD).

AMLO dismantled this political arrangement. The former head of Mexico City ran as the candidate for the PRD in the 2006 and 2012 Presidential Elections, and narrowly lost both times. Both times AMLO accused the victors of corrupt and illegitimate tactics. These actions built AMLO a loyal base of support and a brand as a populist insurgent. To avoid ideological conflict, he broke with the PRD in 2012 and formed his own party, the Movement for National Regeneration (MORENA). AMLO and MORENA won the Presidency in 2018 by a landslide. The once-insurgent won the presidency with 53.5% of the vote versus the 22.3% of his nearest competitor. The alliance of parties that backed MORENA won control of both chambers of the Mexican Congress.

Like American midterm elections, Mexican 3-year midterms are referendums on the incumbent president, their policies, and the current national environment. AMLO has a mixed track record on all three. AMLO promised to change the cycle of corruption and abuse in 2018, but these vices are perceived by some to have engulfed him and MORENA – much like every governing party before him. Organized crime and drug cartel violence remain prevalent. Mexico failed to contain or alleviate the Coronavirus pandemic. AMLO has frequently criticized and derided independent regulatory organizations and the press, leading to opposition claims of potential authoritarianism. Despite this, AMLO remains personally popular. He successfully expanded Mexico’s welfare and poverty assistance programs, expanded the role of state industries and infrastructure, centralized control, and is the face of an expanding vaccine rollout.

The opposition to AMLO lacked a coherent message. The three once-rivalrous big parties united this cycle under an opposition alliance to deny MORENA absolute control. Their campaign platform was one of democratic preservation and dispersion of power. The history of illiberal policies from these parties made them poor messengers – especially at the gubernatorial level where the parties were tied to numerous unpopular former administrations.

AMLO’s goal in this election was to match or exceed the 306 seats (of 500) MORENA and her allies won in 2018. A renewed voter mandate for AMLO’s “Fourth Transformation” would allow him to continue centralization, and a larger majority in the Chamber of Deputies would allow AMLO to introduce constitutional changes.

MORENA and the opposition alliance supported candidates with scandalous pasts and occasional ties to the drug cartels to achieve their electoral goals. MORENA explicitly courted candidates with personal political dynasties, patronage networks, and established personal relationships with AMLO – even if these candidates came with baggage.

Voters on June 6 voiced their disapproval with AMLO and their disapproval with the old guard of Mexican politics. MORENA and her allies are projected to lose 25 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, holding 281 of the 306 they won in 2018. MORENA lost many seats in and around its stronghold of Mexico City, a likely reaction to the government’s mishandling of a deadly metro rail line collapse in May. MORENA sustained support in the poorer south, the northwest, and the rural areas that are more integrated into local patronage networks.

MORENA and her allies nearly swept the governor’s races, and are likely to win twelve of the fifteen states with elections. Many of the new governors have shady pasts. María Campos (PAN) in Chihuahua pled guilty to accepting 10.3 million pesos in bribes between 2014 and 2016; Evelyn Salgado (MORENA) in Guerrero is part of an unscrupulous local political dynasty with past ties to the drug cartels; Ricardo Gallardo (PVEM, a MORENA ally) in San Luis Potosí previously served prison time for embezzlement; Alfonso Durazo (MORENA) the previous Sonora Secretary of Security failed to contain gang homicide and was extorted into releasing el Chapo’s son Ovidio Guzmán; and aloof social media playboy Samuel García (MC, a minor social democratic party presently allied to nobody) in Nuevo León.

The election exposed fault lines, with the more prosperous and urban areas voting against MORENA’s status quo. Since 2018 AMLO has governed with high personal approvals and a culture of infallibility. It seems likely that these elections will shake the electorate’s perception of the government, and the government’s perception of the electorate.

Chile

DDHQ’s earlier analysis of the Chilean constitutional elections noted that the major parties treated the constitutional assembly as just another partisan battleground. We said that voter hopes were fated to clash with the reality of party inertia. These elections coincided with gubernatorial and mayoral contests across the country, potentially pairing the supposedly nonpartisan assembly with the partisan offices. Incumbent conservative President Sebastián Piñera and his Vamos por Chile alliance sought to win one-third of the 155 seats, so that it could block any changes deemed too radical.

The mid-May election was a triumph for those that protested against the government in 2019. Voter turnout was only 43%, a decrease from the 51% that approved initiating the constitutional process in 2020, and 50% who voted in the 2017 Presidential runoff. Turnout decreases were especially notable in conservative strongholds. Those invested in Chile’s constitutional process turned out to vote and selected candidates independent of the tainted establishment. Vamos por Chile won just 24% of the assembly seats, the worst result in the history of Chile’s conservative alliance. Chile’s traditional Socialist left – the former Concertación – won only 16% of the seats. Chile’s alternative left – currently under the name Apruebo Dignidad – won a comparatively strong 18% of the seats. This strong result however is only 5% more than what their alliance won in the 2017 legislative elections.

The big winners were candidates without connections to traditional politics. The reformist and anti-establishment Lista del Pueblo (List of the People) won 17% of the seats, on par with the traditional party alliances. Lista del Pueblo is an alliance of those connected to the 2019 protests. It promises to advocate for the structural changes desired by those protesters. It also promises constituent assemblies to decide their agenda for the convention.

Fewer seats (7%) went to the anti-corruption and pluralistic Independientes No Neutrales (Non-Neutral Independents) list. Another 7% of the seats went to regionalists, local independents, and minor tickets. The final 11% of seats were reserved for Chile’s indigenous groups, established via consensus to give these minorities a seat at the negotiating table.

The Pinochet dictatorship implemented Chile’s present constitution. The constitution was reformed many times to purge it of authoritarian elements, but many view its untouched commitment to conservative and free-market policies as the country’s original sin. The popular La Tercera newspaper circulated a questionnaire to those elected to the convention, and questioned how they might change the policies initially drafted during the dictatorship. 120 of the 155 elected members responded. Almost all electors support limiting the powers of the presidency, guaranteeing water access, environmental protection, indigenous representation, further devolution of powers to local authorities, and supporting gender equality. More contentious is the structure of government – fully federal or devolved and unicameral or bicameral, the necessity of supermajorities on crucial changes, whether to change the constitutional court or not, and whether to guarantee housing and clean energy.

The fear before the vote was that the right would secure enough power to prevent a newer and equitable political system from emerging. Post-election, the fear is that other actors may now have free reign to weaken democratic safeguards and open the door for future authoritarian candidates. The strength of independent lists separate from any candidate running in the November Presidential election makes it unlikely that this fear comes to pass.

Ecuador

Former Banker Guillermo Lasso won the Ecuadorian Presidential runoff on April 11. He came in second place with 19.7% in the initial February Presidential election held on the same day as elections for the Ecuadorian National Assembly. The Assembly results largely matched the first-round presidential results with two key exceptions. First, more of the vote went to minor party lists, some of which won one or two seats in the assembly. Second, conservative voters who united behind Lasso divided their congressional votes between two parties. Half voted for Lasso’s CREO party. Half voted for the Social Christian Party centered on the populous Ecuadorian coast and Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city. This meant that Lasso won the presidency atop the fifth largest party in the assembly – behind the Correra-aligned Union for Hope (UNES), the native Pachakutik, the reformist Democratic-Left, and the Social Christian Party (PSC).

The resulting divisions in the assembly prompted the Union for Hope, the largest party with 36% of the chamber, to seek support from other parties. They approached Lasso under the guise of ‘preserving stability’ and built a majority agreement between the UNES, the PSC, and CREO. Lasso stated his misgivings about this alliance, given his opposition to Correra and his policies, but approved the alliance to prevent an opposition UNES-Pachakutik block from obstructing his policies. The announcement of a Correra-conservative alliance however caused an uproar in the press and social media.

The Assembly opened on May 14 and UNES advanced the alliance’s nominee from the PSC for the Presidency (presiding officer) of the assembly. Lasso now voiced reservations about such an alliance and when the votes were counted, the prospective alliance lost by one vote because of CREO’s abstention. In confusion, the parties postponed the vote for the Assembly’s Presidency to the next day, but it was too late. The PSC followed CREO and broke all agreements with UNES. On May 15 Pachakutik advanced their own candidate, Guadalupe Llori, for leadership of the chamber, which prevailed with the votes of CREO, the Democratic-Left and minor parties. The new alliance then apportioned Assembly committee chairmanships and excluded former Correra allies.

When Decision Desk Headquarters reported on Ecuador two months ago, we ended the piece with the thought that Lasso would struggle to form a governing alliance with the indigenous parties, even though indigenous voters helped him win the presidency. It was however the anti-Correra front that formed a governing alliance. The alliance is not perfect, Yaku Pérez Guartambel, Pachakutik’s 2021 presidential candidate, left the party over its agreement with the conservatives. Yet the alliance is another sign that the people of Ecuador want something other than the old corrupt order.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.