On Sunday, September 25th, Italians vote in an election where the results seem all but predetermined. An alliance of conservative and far-right parties has a commanding lead in the polls which is likely to give the allied parties a large majority of parliamentary seats. Topping the conservative block for the first time is the ascendent far-right and socially conservative Brothers of Italy Party (Fratelli d’Italia or “FdI”). Both outcomes are products of Italian anger and disillusionment with past political leaders and their parties.

Parties and Major Actors

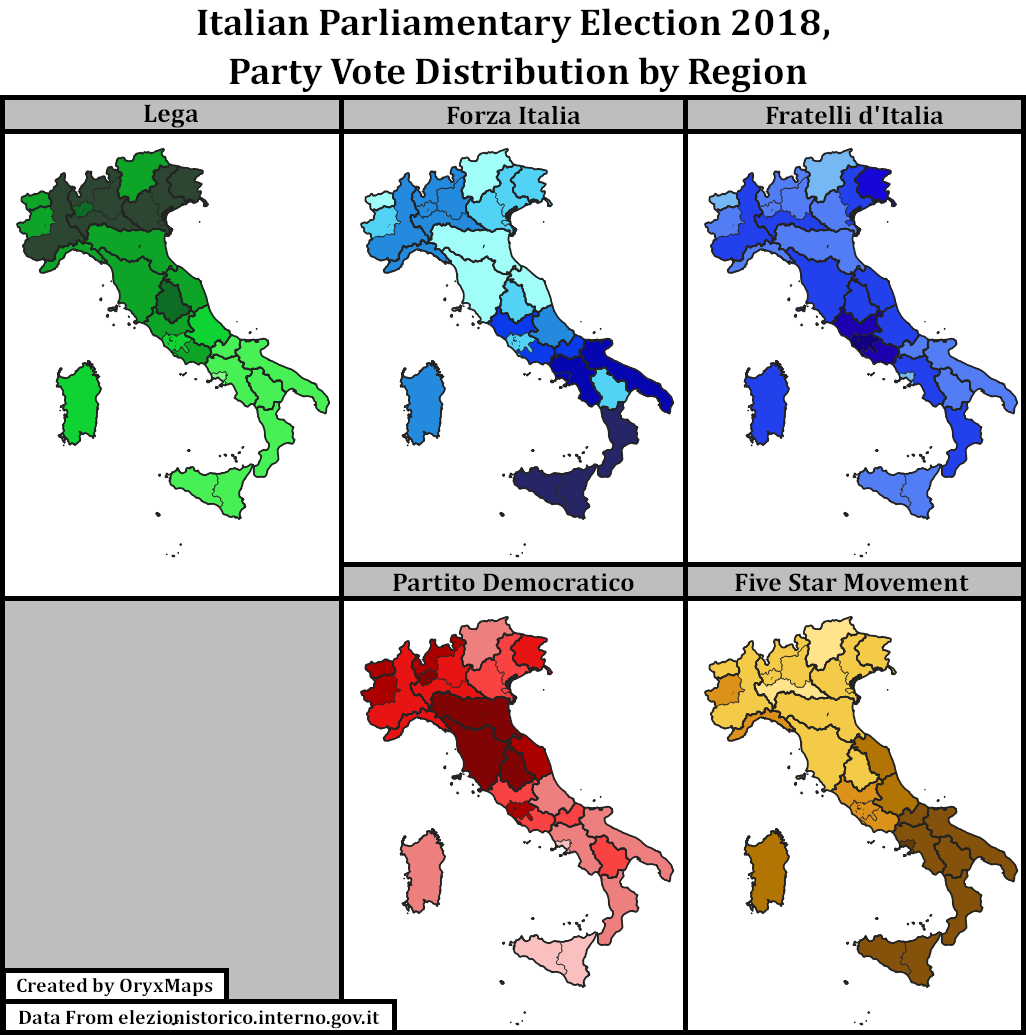

Forza Italia or “FI”: Italy’s main conservative party since leader Silvio Berlusconi abandoned his previous political vehicle People of Freedom in 2013. Berlusconi has been Prime Minister three times since the 1990s. In 2018 FI failed to win enough votes to lead the conservative alliance, underperforming public polling and winning 14% overall. Coalition partner Lega then benefited most from FI’s decline.

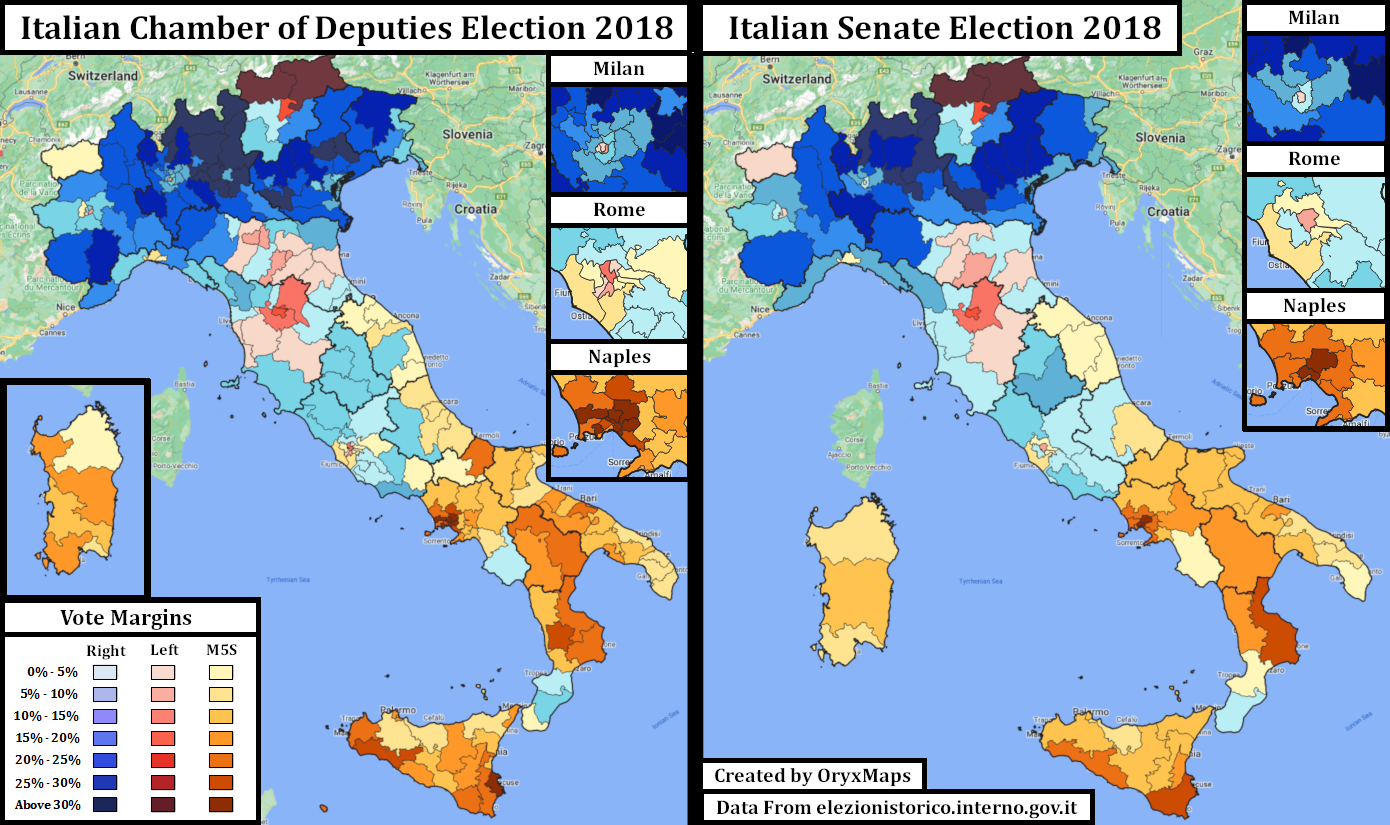

Lega or League: Lega was once Lega Nord, a regionalist party for wealthy conservative northern Italy. Infighting, financial difficulties, and faltering electoral results prompted a change in direction and leadership. Matteo Salvini transformed the party into a Eurosceptic Nativist ticket for the 2018 elections, and shocked observers when he finished second overall and first within the conservative alliance with 17% of the vote. Most of Lega’s support remained in the party’s traditional northern heartland.

Fratelli d’Italia or “FdI”: FdI was the smallest ‘major’ party inside the conservative alliance, winning 4% of the vote in 2018. The FdI notably joined none of the three coalition governments preceding this election. Fdl is strong in central Italy. Critics accuse it and its leader Giorgia Meloni of not just vocal social conservatism and nativism, but also neo-fascism. The party however is best described as nostalgic for a romanticized past era rather than the explicit connotations of authoritarianism and antisemitism associated with that term. This is especially true when compared to predecessor parties like the National Alliance (AN). Several electorally irrelevant micro-parties, such as CasaPound, serve the few Italian voters who do hold those views.

Movimento 5 Stelle or The Five Star Movement or “M5S”: Effectively born out of anti-austerity desires during Italy’s 2012 EU debt crisis, the party positioned itself as anti-political, anti-corruption populist, and independent. M5S’s position and a timely nativist approach garnered the party 33% of the vote in 2018, as it swept the Italian south and put M5S into government. Prominent leaders since 2018 include Luigi Di Maio, Giuseppe Conte, and Mario Draghi.

Partito Democratico or “PD”: Italy’s main social democratic and liberal democratic party since 2006, when multiple smaller and predecessor parties merged. Several minor parties run alongside the PD in major elections as part of the ‘center-left’ alliance. The party led Italy’s government prior to the 2018 election, when former Prime Minister Matteo Renzi led the PD ticket to 19% of the vote. Historically PD is strongest in cities and the part of north-central Italy centered on Tuscany.

Four Years of Voter Behavior

The conservative alliance led the 2018 election winning 42% of the seats, yet lacked an electoral majority. They could not govern alone as a block. Cross-block cooperation made M5S, and its large caucus crucial to any government, and they would lead any coalition with their 33% of seats. Brief negotiations produced a coalition between M5S and Lega in June 2018. The parties agreed upon Law professor Giuseppe Conte as their Prime Minister, with Salvini and De Maio serving as deputy PMs. The unifying issue was immigration. Both parties called for restrictions and crackdowns on immigration coming from the Mediterranean.

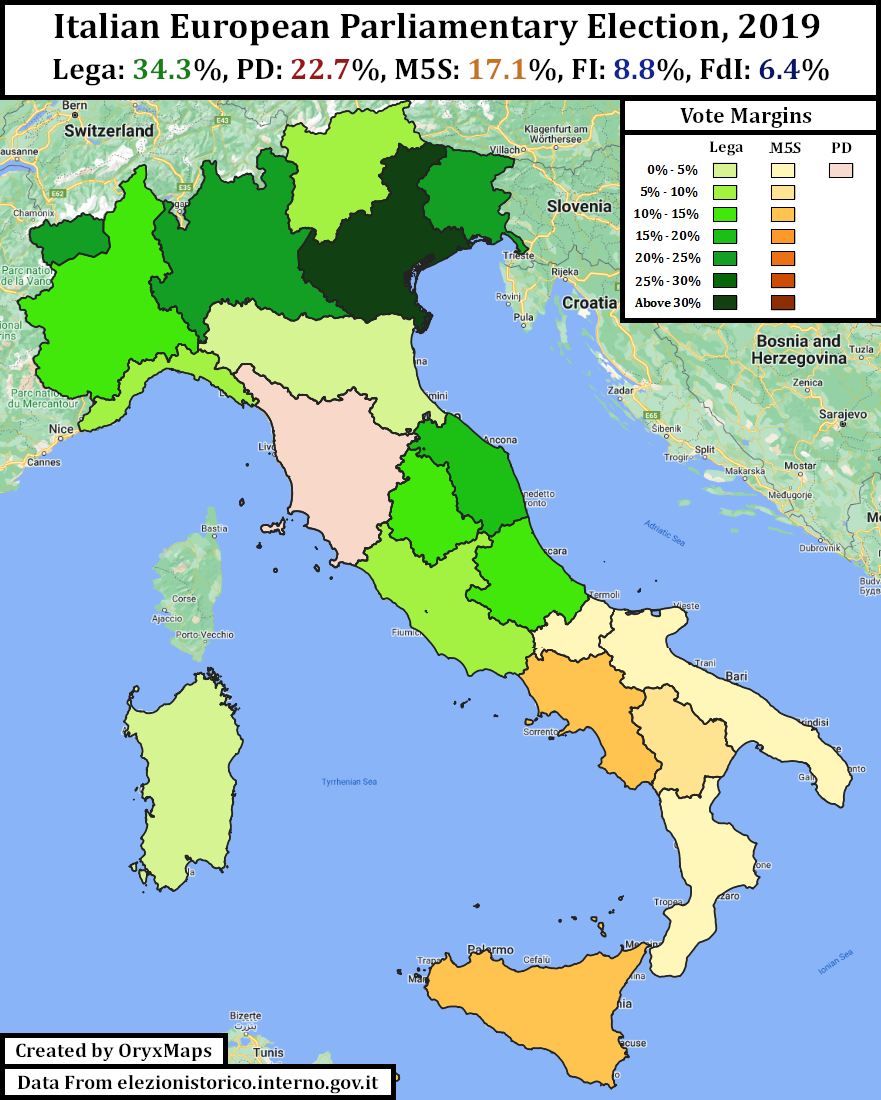

To voters, Lega quickly became the primary attraction in the new alliance. Salvini sought out the cameras and Lega’s wishes often became coalition policy. Voters responded to Lega’s prominence with support for the party. July 2019 was the electoral high point, when some polls showed Lega with almost 40% of the vote, enough to win a single-party majority in Italy’s mixed proportional and first-past-the-post system. Lega attracted some voters from the declining FI, which hollowed down to its core of 5% of the electorate. M5S, which previously attracted voters across the political spectrum, also lost support to Lega among its conservative voters. The May 2019 European Parliamentary elections demonstrated Lega’s successes, with them winning 34% of the vote and gaining support in many southern Italian municipalities where the party had little previous support.

In August 2019, Salvini submitted a motion of no-confidence in his own coalition government. The issue that nominally divided Lega and M5S was the construction of a rail line, but Salvini’s true goal was to force new elections and capitalize upon Lega’s electoral support.

Without any other option, PD and M5S began negotiations for a second Conte coalition government. This was a surprise. PD and M5S were rivals during previous PD governments; and, while PD now had a new leader, Renzi was still the driver of the new coalition. Both parties agreed to adopt new immigration, EU, and economic polices. After PD and M5S aligned, Renzi proceeded to create his own minor party – Italia Viva or “IV,” to maintain his influence within this new government.

Voters responded to these developments in a variety of ways. PD’s new stature attracted some progressive voters from M5S, but many remained loyal. The loss of M5S’s conservative voters to initially Lega left M5S with a focused electorate, one that allowed the coalition partners to run together in local elections and preserve both their distinct electorates. This was also the period where FdI emerged as an electoral force. Lega’s support from far-right voters outside of the North was tenuous. Their failed gamble sent these tepid supporters towards a new ticket. Lega still led the polls but with only 25%, losing former ground to FdI which now polled between 10 and 15%.

The M5S-PD coalition was the government in place when Italy became a Coronavirus epicenter in 2020. Gradual conservative opposition to the health and safety policies slowly coalesced around FdI, pushing its support closer to 20%. Renzi pulled his small group of IV allies from the government in January 2021, when coronavirus-induced economic measures exposed old divisions between him and the populists. The pandemic necessitated a new and broader government and not new elections, but M5S lacked goodwill with their potential partners on the left and right. The expedient option was to bring in a technocrat – in this case, former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi – and form a ‘Unity’ caretaker government that included all major parties. Several M5S politicians left their party out of individual opposition to the Unity government, andFdI was the only party as a whole that did not support the Draghi coalition.

Lega’s decision to join the Draghi government tarnished their credibility as an insurgent, outsider party. FdI’s position in opposition made them the party of change. FdI and Lega began to poll even with each other. Additionally, M5S’s voters began to express dissatisfaction with the party’s direction inside the Unity Government, encouraging some voters to seek out the FdI.

The Draghi government collapsed in 2022. The first major division was economic: the Unity caretaker coalition proposed policies opposed by the majority of M5S and Conte, by now the party’s leader. The second division was Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine. Conte criticized weapon and aid deliveries Draghi and other sections of M5S supported. These factional divisions became official when former party leader Luigi de Maio left M5S and took a third of the caucus with him. Conte responded by withdrawing M5S’s support for Draghi’s coalition. Ensuing maneuvering left Draghi without a majority and the coalition collapsed. Parliament was dissolved and elections called.

These divisions also upended the Italian electorate. All parties within the Italian right have a history with Russian President Vladimir Putin thanks to Berlusconi’s past actions as Prime Minister. Salvini’s prior support for Putin however was part of Lega’s revitalized identity. FdI’s quick embrace of Ukrainian resistance made Salvini the target of popular ire, causing Lega to rapidly lose support especially after Salvini changed his position on the war multiple times. FdI surged past Lega, polling 25% against Lega’s eroding 10 to 15%. M5S’s parliamentary rupture split their remaining electorate. About half of their voters would either follow de Maio or align with PD. The other half stuck with Conte’s rump remainder.

The Upcoming Election

Fdl occupies the coveted image and political message of change, insurgency but also continuity for a different section of Italian voters. The party changed to reflect its growth. Leader Giorgia Meloni preaches a more conciliatory message to EU leaders and fellow politicians, and FdI kicked out vocal extremists, but this hasn’t hurt their image. Italian polls cannot publish results during the final two weeks of the campaign. FdI led both the final published average overall and specifically their conservative allies with approximately 25% of the vote. Overall, the conservatives, combined, have approximately 47% of the vote.

This outcome should not be enough for the conservatives to win outright; the combined left also enjoys 47% of the vote. The legacy of the last four years and how to perceive their results prevented a unified, left alliance. PD leads the center-left continuity alliance with several minor parties – including Luigi Di Maio’s M5S breakaway. This ticket polls at an average of 27% of the vote. Behind PD in the polls is M5S. Conte tried to revive M5S’s former populism in a campaign of opposition to the technocratic government he ended. Voter shifts since 2018 left M5S with an electorate that views itself as more left than right. Fundamental disagreements between parliamentary leaders prevented an alliance with any other party. M5S retains an average of 13% of the vote. Finally, there is the liberal alliance between Renzi’s IV and the minor Action (Azione) party; combined they poll at 6 to 7% of the vote.

Under current Italian election law, 37% of seats are allocated based on first-past-the-post districts, 61% are allocated proportionally based on regional groupings, and 2% are reserved for overseas expatriates. This is the same in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, the two parliamentary bodies. Simultaneous elections means both bodies’ compositions are identical and aligned. The conservatives’ 47% of the vote is large enough to defeat the PD alliances’ 27% and M5S’s 13% in all but their strongholds. These victories, when added to their large share of the proportional seats, will put the conservative alliance over the 50% majority finish line.

Secondary questions about whether the conservative alliance will win a super-majority of seats or if the conservatives can form a government with only two of the coalition parties gain relevance if polls about the election outcome are correct. The conservative parties suggest expanding executive power and establishing a pseudo-presidential Prime Minister if the alliance wins 66% of the seats, the benchmark to change the Constitution, ignoring that Italy already has a figurehead Presidential Head of State. There are several parties within the conservative alliance, but a large win under the latter secondary outcome means only two parties are needed for a government. This result means forming a government is easier than with more coalition parties. The resulting government is less likely to collapse, as has been shown to be common in Italian politics.

Italian voters want change. They wanted change in 2018, when they put M5S in power, but change did not come as desired. M5S’s lack of positions allowed their partners to constantly sway policy. FdI’s positioning as Italian political change agent placed the party in opposition to the rest of the Italian political system. Fdl’s alliance within that system means the conservatives could win far more support than Italian voters expect, potentially bringing changes they might not desire.

This analysis was written by Benjamin Lefkowitz independently of any third-party organization. All views, opinions, and analyses are those of the author.