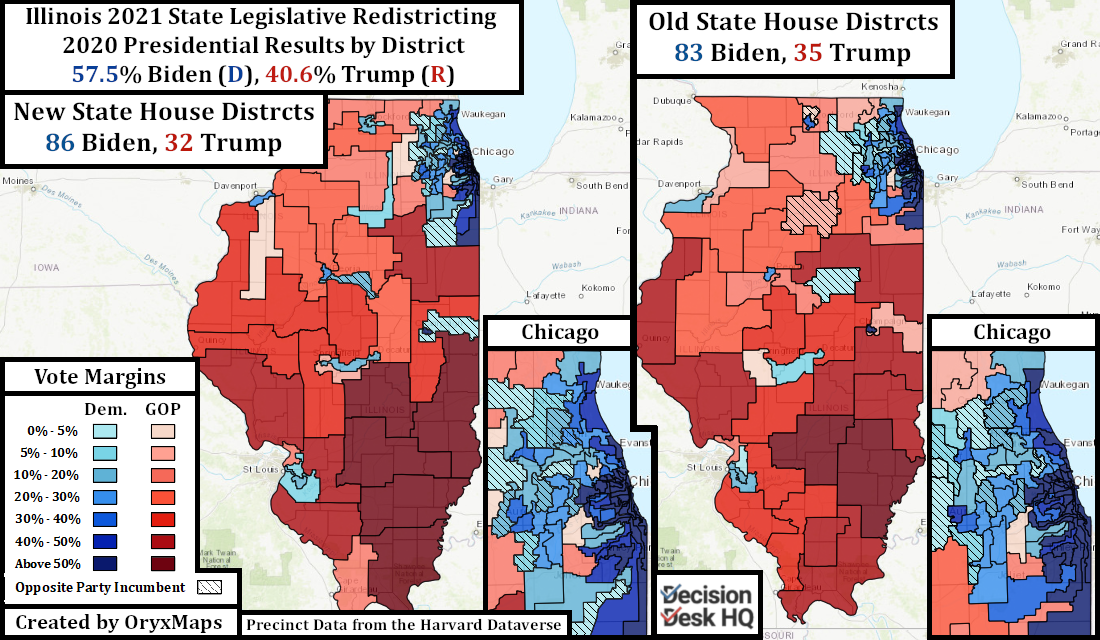

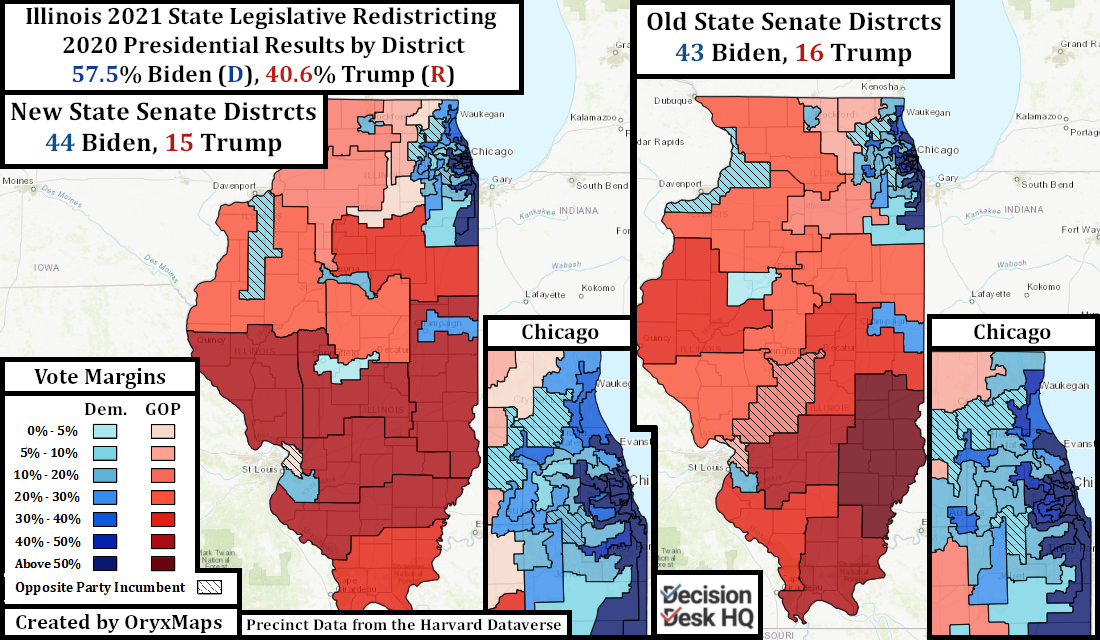

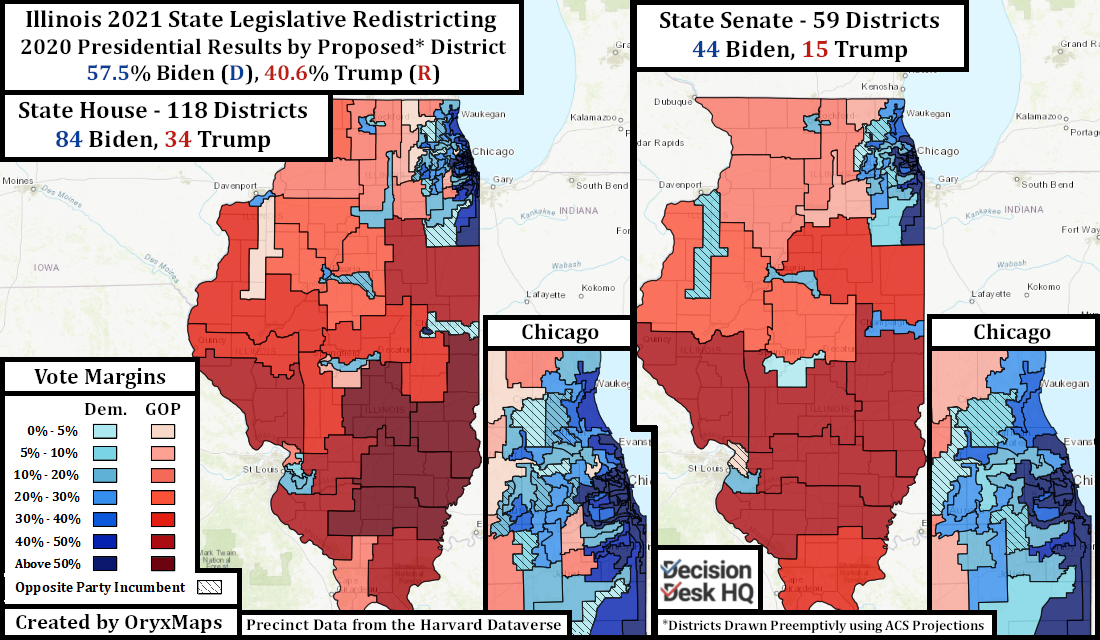

The Illinois General Assembly approved new State legislative maps in the evening of August 31, making Illinois the first state to legally complete part of the redistricting process. State Legislators previously approved temporary maps created from the American Community Survey (ACS) population projections to meet with legal deadlines. The State legislative maps passed on Tuesday mostly modified the preliminary maps to match Census population numbers with a few key exceptions. These maps reinforce and potentially expand the caucus of office-holding Democrats who drew them.

The Two Maps

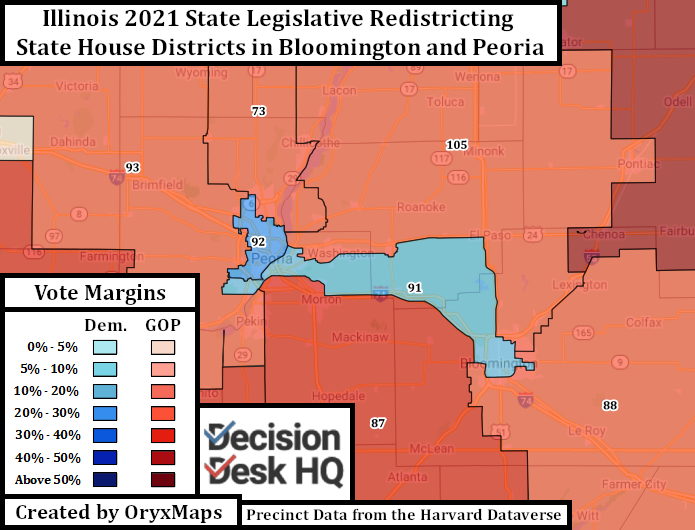

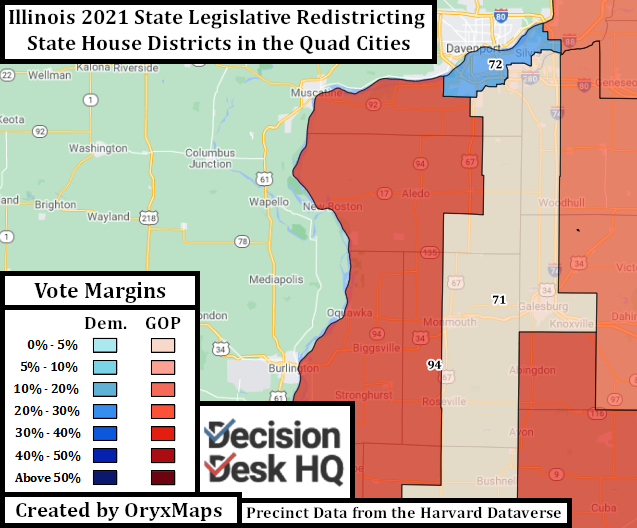

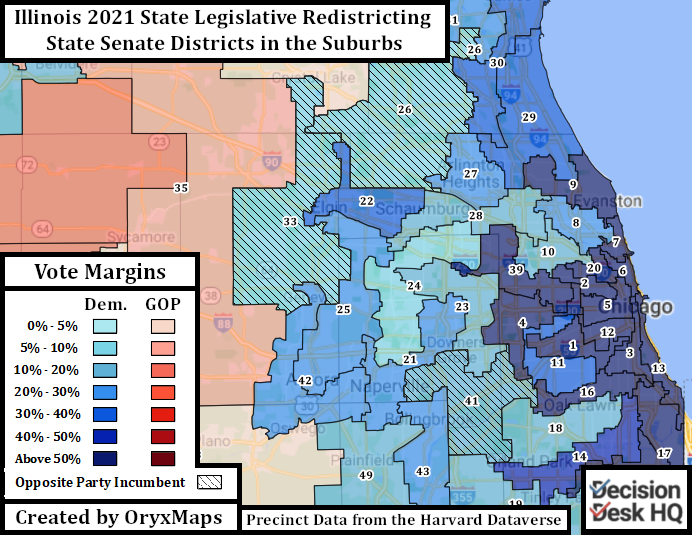

Illinois law requires “nesting” State House districts within State Senate districts. The 118-seat State House is twice the size of the 59-seat Senate; each State Senate district is built from two House districts. This rule challenges partisan mappers: Senate districts designed to be safe for one party must have two constituent, safe House districts or at least one that overwhelmingly supports the favored party.

Downstate Illinois’ districts demonstrate how the nesting requirements influenced results. Bloomington and neighboring Normal have the population to support a compact Democratic State House district on their own. This hypothetical district would lack a partner for the Senate and, instead, be paired with a district in Republican, rural areas. The solution is to drag the district into the suburbs of Peoria so that the two Democratic House seats touch. The pairing fortifies Democratic control of Senate District 46 in Peoria which was slipping away from the Democrats because of the city’s previously nested rural partner district.

The Quad Cities in northwest Illinois demonstrate another compromise forced by nesting rule, only in this instance the Senatorial lines dictated those of the House, rather than the other way around. Republican Neil Anderson won Senate District 36 in 2014 and held it in 2018 despite the district’s Democratic topline. The desire to add Democratic and remove Republican voters from the district meant removing the counties to the north of Moline and adding a southern tail. These changes make Senate District 36 about three points more Democratic.

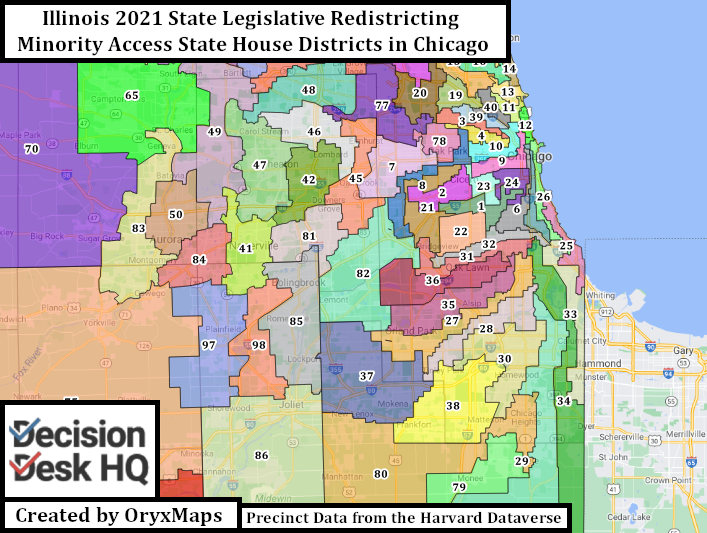

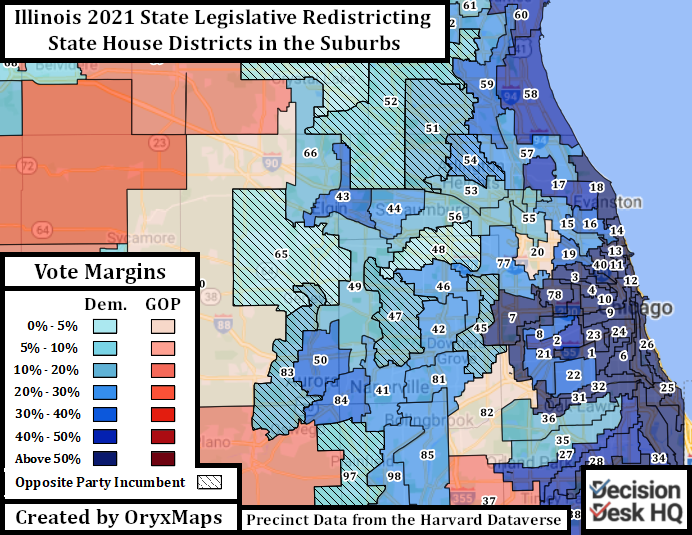

Illinois’s minority population is concentrated in racially polarized South and West Side Chicago neighborhoods and their immediate suburbs. Minority concentration necessitates visually unappealing ‘snake-like’ districts that pair overwhelming minority communities with distant White neighborhoods. This prevents unlawful levels of minority concentration and dilution of minority voter access. Democratic mappers cleverly drew the lines to put White Republicans, rather than White Democrats, alongside the Democratic-favoring minority voters of these districts.

What Changed, What Didn’t

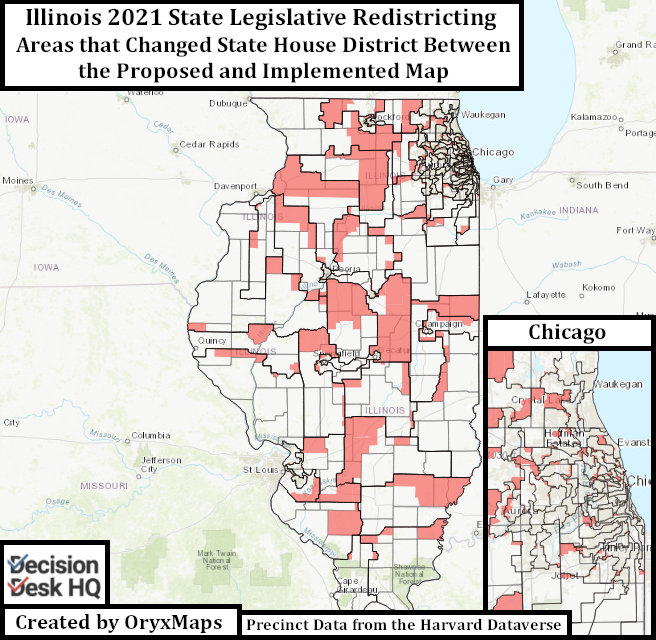

Democratic mappers passed preliminary plans in June based on ACS population estimates. Illinois legislators went through this roundabout process to comply with legal deadlines surrounding the State Legislative process, a deadline that if not respected would give the Republicans a seat at the table.

There are several major changes to the passed maps from the initially proposed ACS-based plans. House Districts 63 and 65 on the edges of the Chicago suburban “Collar Counties” – one in McHenry County and one in Kane County – both changed significantly. Alterations to the lines between the provisional ACS and the final maps changed both seats from Trump 2020 districts to seats Biden won in 2020. These edits necessitated population transfers between neighboring districts, resulting in cascading edits across the rest of the rural Northwestern legislative districts. The rural seats now orient themselves East-West rather than North-South.

Most Illinois districts marginally changed between the preliminary and final maps. The increasingly Democratic and heavily gerrymandered Chicago suburban districts remained in place. In 2018 and 2020, Democrats flipped many House and Senate seats drawn to elect Republicans, and these new incumbents desired protection. Blue parts of the suburbs, such as Aurora and Bolingbrook, traded precincts with competitive seats. The component House districts that made up Senate seats shuffled around, pairing the most Republican House districts together and giving Senatorial incumbents more Democratic voters.

After protecting incumbents, Democratic legislators then appear to have noticeably altered at least one House district in each Collar County. Each is now a potential pickup target. Biden won all but one of these districts under the lines drawn in 2011, but the following Republican-held House districts became more Democratic through redistricting: 45, 47, 51, 54, 79, 83, and 97.

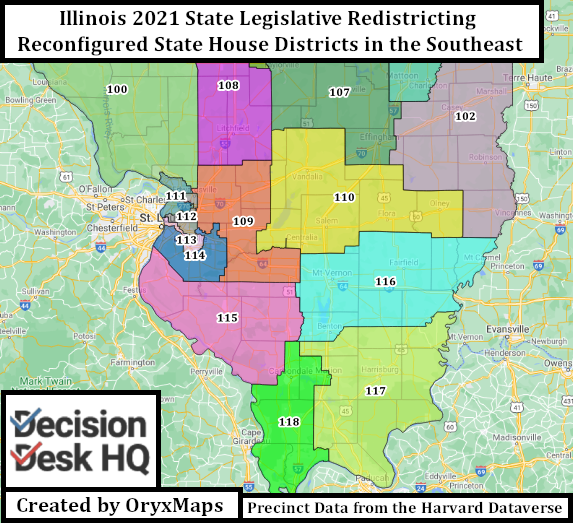

Democratic Legislators also used the pen to force incumbent Republicans out of the chamber. Mappers drew districts in the southeast of the state East-West rather than North-South to separate the bases of support for several disliked Republican legislators. These Republicans now reside in the same district, with the pieces of their former districts redistributed to other Republican seats. Separated from their established networks of support, these GOP incumbents potentially face ambitious primary challengers.

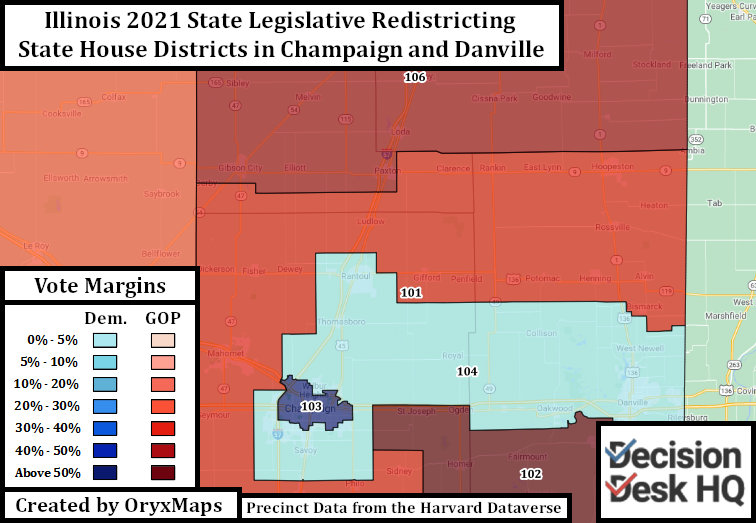

One place where the Democrats did not gerrymander themselves a new seat, despite the fact they could, is around the college town Champaign. Champaign and its eastern neighbor, Urbana, are overwhelmingly Democratic. When paired with nearby Danville the region has the votes for two reliably Democratic districts. Had this occurred, incumbent State Representative Carol Ammons, who lives in Urbana, would have found herself forced to take in large numbers of new constituents. It is better for the incumbent to keep the two college towns together and use the remaining precincts to build a marginal Democratic seat, as is done in the implemented maps.

Gradual Gains

The immediate effects of these redistricting plans however may not instantly be apparent. Topline results take a few years to trickle down to lower-level races. The GOP maintains a large delegation from Collar County Biden districts, and until 2020 the Democrats had a handful of state legislators elected from rural Southern Illinois. Even though Democratic mappers drew favorable lines that appear to immediately target incumbent Republicans, the transition will still take time.

Several other Biden-won suburban seats still remain distant targets at the moment, despite the Presidential topline. Their lines are designed to elect Republicans now, but potentially become future targets when the suburban Democratic base grows larger.

The lines still may marginally change. These passed maps still remain under scrutiny by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, who alleges that mappers did not draw an adequate number of Hispanic districts.

To that end, the first goal of those in Illinois with the power to redistrict was to protect rather than expand the Democratic Legislative supermajorities. These maps accomplish this goal.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.