Fragmented political systems, extreme wealth gaps, economic uncertainty, instability, corruption, authoritarian tendencies, and personality parties centered around populist political dynasties – these are the unfortunate trademarks of Latin American democracy. These tendencies historically facilitated violence, single-party rule, and military juntas, which further normalized and perpetuated the political system. Elections devolve into contests between ‘least bad’ candidates because no political position is free from these corrupting undercurrents.

Much of Latin America uses a Two-Round Runoff system for electing presidents, but proportionately elects politicians to national legislatures. This system protects and perpetuates Latin American political dysfunction. Proportionality encourages the proliferation of political parties, dividing the political system into numerous camps. Small, loyal, party bases are willing to ignore their own side’s failings if the alternative is empowering those viewed to be anti-democratic. Presidential runoffs force electoral consolidation to give one candidate a majority of the vote, but universal political deviancy muddies the process. Instead of congregating around the candidate most agreeable, voters must choose the candidate with whom they disagree least.

Two Latin American countries – Ecuador and Peru – voted on Sunday April 11. Chile originally scheduled a third election for this date, but rising Coronavirus cases delayed the vote until May 16. The circumstances behind the three elections vary. Ecuador held the necessary Presidential runoff after the initial February 7 general election; Peru held their general election and will require a future runoff; and, Chile planned a vote to determine the composition of its Constitutional Assembly responsible for drafting a new constitution. All three elections feature the same issues: political corruption, inequality stemming from economic liberalism, and the struggle to escape an authoritarian past.

Ecuador

Ecuador’s Operation Condor (United States backed South American Juntas) dictatorship ended in 1979. Subsequent Ecuadorian governments pursued policies of economic liberalization and exploitation of the country’s petroleum resources. These policies eventually brought inflation, economic collapse, political instability, and the adoption of the U.S. dollar. Ecuador responded by electing Raphael Correra in 2006, who would win reelection in 2009 and 2013. Correra governed as a populist leftist in the tradition of the “Pink Tide” (a wave of South American Socialist governments) and focused on reducing poverty, the income gap, unemployment, health care access, and “freeing Ecuador from the shackles’ of globalization.” Correra’s rule was not free of Latin America’s political vices – Correra removed term limits in 2015 to open the door for a future fourth election, and in 2018 and 2020 Ecuador brought corruption and abuse of power charges against the former President.

Correra hand-picked his 2017 successor, Lenin Moreno. Moreno pledged to continue Correra’s policies but eventually reneged and implemented austerity to combat a growing national deficit. Protestors took to the streets in October 2019 as a response to planned cuts to low-income subsidies, forcing Moreno to relent. Moreno’s economic and social policies – in particular those related to resource extraction – sank his approval ratings, ruptured relations with Ecuador’s Indigenous community, split the government’s PAIS party, and led former President Correra to disavow his former ally.

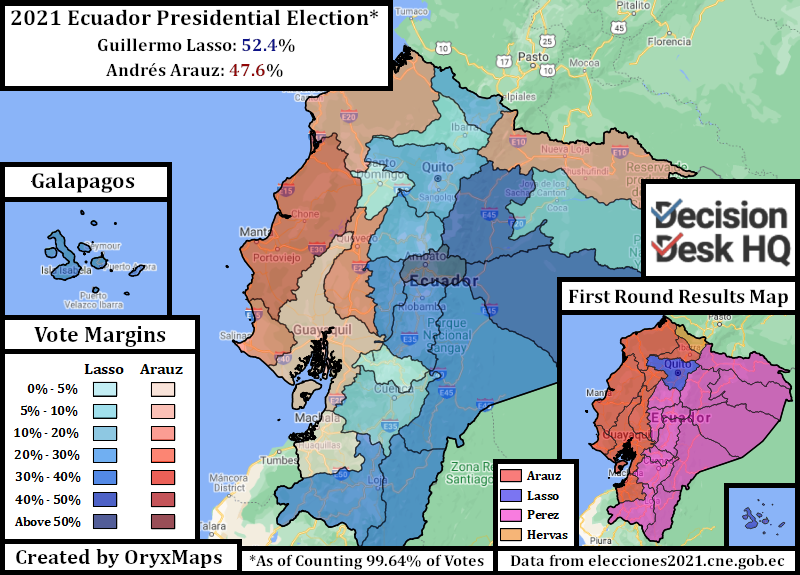

The 2021 election was a referendum on both Moreno and Correra. Correra and his allies backed Andrés Arauz as the candidate who would resume the former president’s policies. The Indigenous vote however abandoned the Correra block, making Arauz vulnerable. Yaku Pérez Guartambel ran a campaign opposing the government’s extraction policies that isolate, contaminate, and impoverish Ecuador’s Indigenous communities. Liberal banker Guillermo Lasso finished just ahead of Yaku Pérez in the February election, a result that led to a recount and allegations of fraud. Yaku Pérez refused to endorse Lasso in an anti-Arauz runoff alliance, and the Pachakutik Indigenous party encouraged their voters to cast a blank vote and reject both Lasso and Arauz. Both candidates campaigned for Indigenous voters; Arauz promised to officially recognize the Indigenous Nations and Lasso promised to give the community more say over extraction policies and halt plans for future extraction in Ecuador’s region of the Amazon.

Some Indigenous voters voted “blank” – the number of empty ballots increased by approximately 600K when compared to February 7 – but the majority preferred the former banker Lasso. Lasso won the presidency with 52.4% of valid votes to Arauz’s 47.6%. Lasso’s election is a break from the Correra and the Moreno legacies, both of whom remain polarizing figures. It is uncertain how much the former banker can accomplish. Right-aligned parties only won approximately 30% of the National Assembly during the fragmented parliamentary election on February 7. Policy initiatives would likely require the support of the enlarged Pachakutik party, and it seems unlikely Lasso can repeat his success among Indigenous voters with their politicians.

Peru

The presidency of Alberto Fujimori shaped modern Peruvian politics. 1980s Peru was chronically unstable: runaway inflation, shrinking incomes, rising cost of living, political corruption, and the emergence of violent insurgent groups such as the Marxist Shining Path. The Japanese-Peruvian Fujimori won the presidency in 1990 promising dramatic reform. Fujimori stabilized the economy through liberalization and structural adjustments while expanding the safety net, and defeated the Shining Path through direct confrontation and paramilitary counter-insurgency. Fujimori’s 1992 ‘Self-Coup,’ which dissolved the Peruvian Congress and reformed the constitution to empower the presidency, allowed the president to implement his reformed unimpeded. He presided over Peru until 2000 when protests and bribery allegations ended his attempt to win a third term. Fujimori now sits in prison, convicted of human rights violations and corruption charges. Despite this, the former President’s approvals remain high among some Peruvian communities, and many consider him to be a successful yet flawed President.

Peru cannot escape the legacy of Fujimori. His personalistic approach to politics motivated others to launch personality parties of their own, including one led by his daughter, Keiko Fujimori. The personalistic nature of the parties leads to candidates selling their votes to various coalitions in exchange for material benefit. Corruption scandals are constant and prominent. Polls find Peruvians faith in Democracy at an all time low.

Events since the 2016 election exacerbated political discord. Peru elected economist Pedro Pablo Kuczynski as President with 50.1% of the vote to Keiko Fujimori’s 49.9% in 2016, but Fujimori and her allies won a majority in the Congress. Kuczynski resigned in 2018 after being consumed by the Brazilian-based and Latin American-wide Odebrecht Corruption Scandal (also known as Operation Car Wash), alongside videos of the government buying votes in Congress to support the president. Vice President Martín Vizcarra assumed office and promised reforms to restore political trust. Vizcarra called a snap election for Congress in January 2020 in an attempt to win backing for reform, but even though voters rejected Fujimori, they failed to return a majority for change. The Congress impeached and removed Vizcarra in 2020 for mishandling the Coronavirus crisis, which briefly brought Manuel Merino to power before he resigned in favor of a fourth president on November 15, Francisco Rafael Sagasti. Sagasti now heads a transition government to avoid scandal until the voters confirm a new president.

The Peruvian presidency was not the only section of the country to fall to instability. The Odebrecht scandal implicated more Peruvian politicians and former Presidents – including both Keiko and her brother Kenji Fujimori – on money laundering and corruption charges. The Peruvian judiciary faced its own crisis of confidence when government prosecutors were caught selling influence. Peru failed to contain the Coronavirus pandemic leading to one of the highest death rates globally. The pandemic weakened the Peruvian economy, widened the income gap, and further impoverished Peru’s Indigenous population. Peru’s minister of health resigned when 487 prominent politicians were found to have utilized their positions to receive coronavirus vaccinations ahead of schedule.

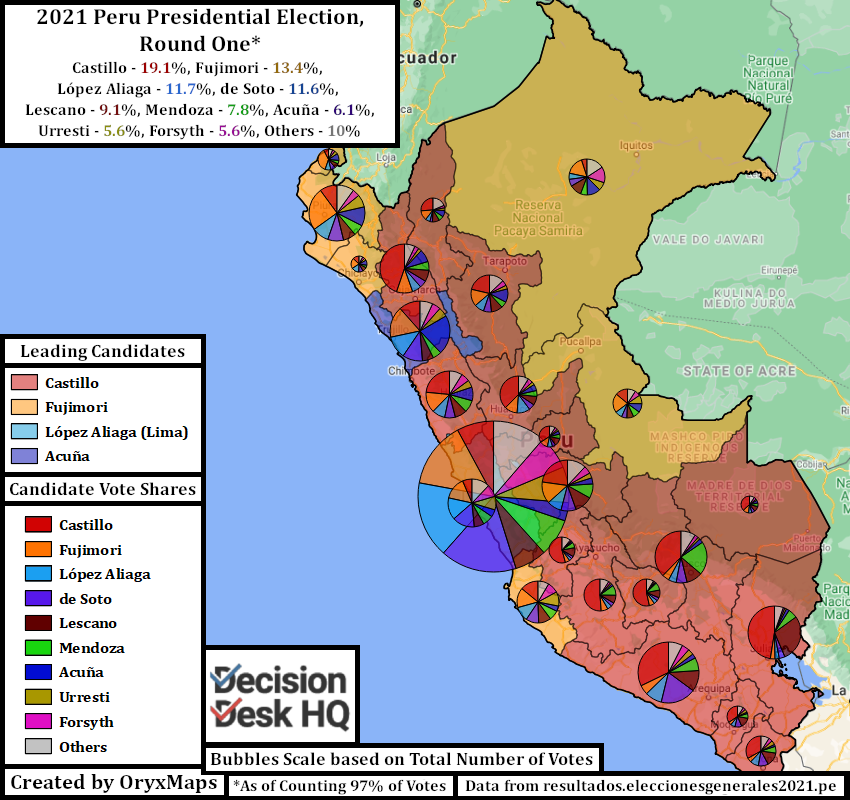

Both voters and politicians want the crisis to end, but they cannot agree how. On April 11, voters chose between an unprecedented 18 presidential tickets – twelve realistic – two of which contained former Presidents of Peru. Some candidates promised reform and change; others, like Keiko Fujimori, promised a strong will and a hard line. No candidate could mathematically expect more than 20% of the general vote.

Results suggest a startling outcome. Pedro Castillo, a rural socialist teacher with past connections to the Shining Path came in first place with 19.1% of the vote. Castillo seeks to redraft the country’s constitution to give more power to the rural poor. Castillo stated that he would close Congress and reorganize the Constitutional Court if either attempts to block his revolutionary platform. Keiko Fujimori, who promises a return to her father’s policies, won the second slot in the runoff with 13.4%. Both candidates advance to a June 6 runoff. The Congress is however proportionality fragmented between eleven personalistic parties, neutering the successful implementation of either candidate’s extremist platform. Parties opposed to Castillo have a majority of the seats, but Fujimori also lacks a majority despite the many parties’ supposed ideological similarities. Both candidates could potentially be impeached and removed from office, just like their predecessors.

Chile

US President Richard Nixon and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger used U.S. resources to assist the Chilean military overthrow their elected socialist President, Salvador Allende, and replace him with Augusto Pinochet’s junta in 1973. The Pinochet regimes’ neglect for human rights paired with extreme anti-Communism and conservatism defined Latin American dictatorships set up under the aegis of Operation Condor. Pinochet governed extrajudicially for seven years, and then drafted and implemented a conservative constitution in 1980 that theoretically set a presidential term to eight years. Voters rejected the dictator in a 1988 plebiscite, voting ‘no’ and denied him another eight-year term. Pinochet stepped down and transferred power to Patricio Aylwin in 1990 following a new democratic election.

Chile’s 1980 constitution survived the transition to democracy, with adjustments to facilitate a return to electoral democracy. The loose grouping of left-aligned former opposition parties known as the Concertación governed Chile from 1990 to 2010, but the Concertación government’s only ever reformed the constitution to remove remnants of authoritarianism. The liberal, market-favoring provisions remained in place. Sebastián Piñera’s election in 2010 was the Concertación’s first nationwide defeat, opening the door to a new electoral era. Low approvals following Piñera’s first term from 2010 to 2014 and Michelle Bachelet’s second-term neo-Concertación government from 2013 to 2017, led to the emergence of smaller party alliances separate from the larger conservative and neo-Concertación alliances. Bachelet’s second term began with the promise of structural change to benefit the working poor, but her government never acted on these proposals. Piñera’s election to a second term in 2017 confirmed that Chile could consitently elect right-aligned governments, even though these governments internally compromised with rump Pinochet apologists within their ranks. Piñera’s return also halted serious electoral reform.

Chile’s market-oriented policies came to a head in 2019 under the incumbent Piñera administration. The Santiago capitol region moved to increase public transportation costs, an unacceptable decision to those Chileans living in poverty. Protestors took to the streets but were met by force and government crackdowns. The government’s use of excessive force enflamed the protest into a mass political movement of over a million people against structural inequalities in Chilean society and the unpopularity of the state. The National Congress responded by agreeing to hold a plebiscite on whether to draft a new Chilean constitution.

The Coronavirus pandemic delayed the initial referenda from April 2020 to October, but plebiscite voters overwhelmingly approved a new constitution by 78.3% to 21.7%. Voters additionally confirmed that an elected constitutional convention would be responsible for the new constitution. Convention delegates would be elected proportionately by state with 17 of 155 seats reserved for Indigenous Chileans. This proportional process is similar to how Chile elects her current Chamber of Deputies.

Contesting the delegate elections are Chile’s three main party alliances – the Right under Vamos Chile, the neo-Concertación left under La Lista del Apruebo (“The Approve’s List”), and the alternative left under Apruebo Dignidad (“I approve dignity”) – and a host of minor parties, independents, and “Disapproval” lists. Suring Coronavirus cases postponed these elections from April 11 to May 16.

Many contesting parties view this constitutional opportunity as another partisan arena, potentially damaging the process’s legitimacy. Piñera is unpopular, but the minority that still approve of his administration will vote for the Vamos list to block constitutional developments. The multitude of opposition parties will need to find a way to work together on a common platform of reforms and not undermine the constitutional process by devolving into factional infighting, a feature of the multiparty alliances.

The future of democracy in Chile, Peru, Ecuador and even Latin America itself remains uncertain.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.