The second after Big Ben struck 10 pm in the UK last Thursday night, the blame game began in the Labour party. Why had the party, that had won three straight landslides with Tony Blair just 20 years ago, lost four straight elections? How had, not just the general population of the UK, but previously Safe Labour seats elected a Boris Johnson lead Tory government after 9 years of previous Tory governments? How did the people pick the same Tory government, lead by yet another rich Southern Tory, claiming that he could reverse the damage done by the same government he held a cabinet position in?

“We knew it would be tough, with Brexit dominating this election” said the Labour Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer (and de facto Deputy PM, had Labour won) John McDonnell to Andrew Neil on the BBC Election Night results program at 10:16 pm. Quickly deflecting the blame away from his friend and leader Jeremy Corbyn, he talked about how no other issue than Brexit could cut through in the election, and that it ultimately lead to Labour’s worst performance since 1935. By 10:22PM, we had another possible explanation, from Laura Kuenssberg, the political editor of the BBC. “Candidates have said to us again and again and again, we have a problem with Brexit, but we also have a problem with the leadership” clearly pointing the finger at Jeremy Corbyn as one of the biggest sources of Labour’s struggles with voters.

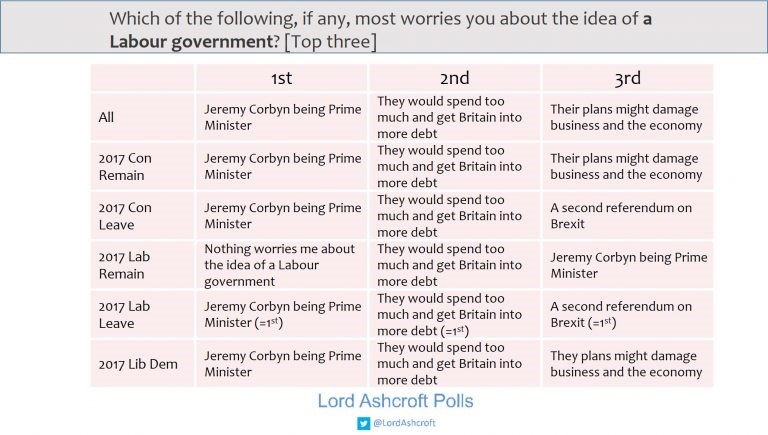

Which version is correct? Did this election truly show a deep hatred of Jeremy Corbyn and his policies? Or was the electorates hatred of Corbyn not about him, but about his Brexit policy? It depends on which data you look at. According to a Lord Ashcroft poll from the middle of the campaign, the thing that worried UK voters the most about a Labour Government was Jeremy Corbyn becoming Prime Minister. Of the various 2017 subgroups (Con/Lab Leave/Remain voters) fears of Corbyn dominated. Surprisingly, even with 2017 Labour Leave voters, Corbyn moving into No 10 was their biggest concern, tied with Labour spending too much, and a second EU Referendum. This data would seem to agree with the Kuenssberg theory of the election: Jeremy Corbyn was a historically unpopular Labour leader, and as such cost Labour the election. That the main reason Labour lost traditionally working class Labour union seats was because of Jeremy Corbyn and his very leftwing policies.

However, since the election has happened now, we can look at actual electoral data, instead of just a pre-election poll. So what does the data say? It paints a somewhat different picture:

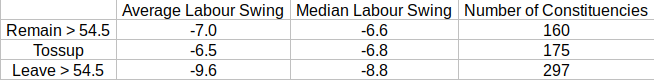

A simple analysis, comparing the Average and Median Labour Swing in Strong Leave/Remain seats (More than 55% rounded for either side) and Tossup Seats (between the Strong Leave/Remain) shows striking differences. The first number that jumps out is the sheer number of Strong Leave seats, compared to Strong Remain and Tossup Seats, as almost half of the 632 Great Britain seats voted Strongly to Leave the EU in 2016. Another important point to make about this data is that since the Referendum results were not recorded on the constituency level, only at a larger regional level, these figures are the official estimates, with margins of error included, conducted by Professor Chris Hanretty, a political scientist at Royal Holloway University.

This data paints an interesting picture of what happened to Labour on election night. It shows that although Labour lost votes across the board in all types of seats, the swing against them in Strong Leave seats was much stronger than in Strong Remain, and closer Referendum seats. Additionally, it’s interesting to see that the lowest average swing against Labour was in those Brexit Tossup seats, areas that were not decisisae for Leave or Remain. That would seem to indicate that voters who elected to Leave the European Union in 2016 voted even more against Jeremy Corbyn than voters who voted to Remain, or voters that lived in areas that were mostly undecided.

This suggests that although there was a broad, general dislike of Corbyn with the electorate, there appears to be an even stronger dislike of Corbyn with voters who wanted to Leave the European Union. What reasons could there be for this? Possibly because Corbyn’s ambivalent Brexit policy (Negotiate a new deal, hold another referendum, possibly even vote against that newly negotiated deal) was deeply unpopular with those Leave voters. However, from the Lord Ashcroft poll, many Labour Leave voters seem to think Labour had unrealistic spending policies as well, which would suggest that their dislike of Corbyn was even deeper than his Brexit position. This secondary concern also seems to appear in other Western countries, as leftwing parties are losing their former working class base with fears that they are becoming more metropolitan and ignoring the concerns of voters who live in the heartlands.

However, it is now important to examine the swings against Labour in the Remain seats. Although nobody would ever consider a 7% swing against a party “good” their smaller losses with Remain voters stands out as a small ray of light on a very dark night for the party. In this election, Labour, and Corbyn by extension, didn’t even have the most Remain Brexit policy. The Liberal Democrats, a centre-left party, ran on a promise to hold a second referendum, and cancel Brexit altogether. Why did Labour not lose more voters in these areas, specifically to those same Liberal Democrats? Even though many Remain voters appeared to strongly dislike Corbyn (many of which were never Labour voters before 2017), they did not behave in a similar manner to their Leave voting cousins by abandoning the Labour party. Why? Possibly because of Corbyn’s Brexit policy. Many of those Remain voters would have seen a vote for Labour as the only way to achieve a second referendum, and therefore, although they may have disliked Corbyn for many different reasons, still stuck with him because he was their best hope to stop Brexit.

With that final point, we have now come full circle. Although it seems that Corbyn was deeply unpopular will all groups of people, it would appear as though his Brexit position cost him even more deeply with Leave voters, but at the same time cost him less with Remain voters, as they potentially saw a vote for Labour as a last chance to stop Brexit. What does it all mean? It means that although Corbyn’s unpopularity cost him deeply with the electorate, Leave voters seemed to dislike him more than Remain voters. How could this be? A possible example of this could be, sometimes when you get into an argument with someone, that argument is not actually about what you are arguing about. For example, with a couple in a relationship, an argument about not doing the dishes at night could actually have a deeper meaning about not caring about the other person’s wishes. In this context, Leave voters apparent deeper hatred for Corbyn might be about Brexit, but when confronted by pollsters, or to talk about it in general conversation, they would find another reason to be angry at Corbyn. It is not unreasonable to think that a Labour Leave voter, mad with Corbyn and the party for their apparent dismissing of the wishes of Leave voters, would see coverage of the Labour election platform, and find faults with spending promises, using those an excuse to vote against the party that they had voted with for decades. Additionally, it is not impossible to imagine Remain voters waving away legitimate criticism of Corbyn in order to justify voting for Labour in the hopes of a second Referendum on European Union membership.

This argument, about whether it was Jeremy Corbyn, Brexit, or Left wing policies that cost Labour the 2019 election will be relitigated again and again until the next UK election (in a similar manner to the arguments about why the Democrats lost working class voters in the 2016 Presidential Election). Honestly, there might never be a full and complete answer. Partisans on either side of the debate will make cases in their own self interests. All of those arguments are legitimate in some way, as there is data that potentially points to both sides being right. The problem is that the battle inside Labour won’t be about finding objective truth, but finding the answer that wins their faction the prize of the leader and deputy leadership positions early next year. Whether they can win in 2024 depends on whether the view that wins that leadership happens to find favour not just with the minority in the Labour membership as Corbynism did, but whether their new direction can finally rally the country to Labour for the first time since Blair.

Robert Martin (@LeanRobert18) is CEO and Founder of LeanTossup.ca and a Decision Desk HQ contributor.