Voters in Israel are going to the polls today for the fourth time in two years. The nature of Israeli politics and it’s electoral system are at the heart of such frequent votes.

Political, ideological, and social polarization emerges most often in electoral systems with elements of electoral majoritarianism. The societal animosity which foments polarization rarely emerges in proportional systems because parliamentary cooperation is needed for the system to function. Otherwise stable, proportional systems require unresolved, multi-generational conflicts concerning the personal identity of the voters, their democracy, and even the national identity to polarize into a multitude of inflexible camps.

This is the reality of Israeli politics. Israel goes to the polls on March 23rd in its fourth election since 2019 because no single party can form a stable majority government. The potential existed for even more elections in 2020, but the Coronavirus intervened and politicians perceived a need for a temporary government. Parties opposed to renominating Netanyahu won 50% or more of the seats in the Knesset (Israeli Parliament) every time, but factional polarization made cooperation impossible. Confrontational factionalism and political expectations allowed Netanyahu and his (conservative) Likud Party orchestrated a beneficial post-election outcome from each electoral contest.

Why Factionalism?

The traditional perception of Israeli demographics is a dualistic divide. There are those who identify with the majority Jewish Israeli population and those who identify with the maltreated Arab minority. This perception falsely portrays the two largest communities as unified when there is sometimes no agreement between supposed allies.

The Jewish community can be subcategorized into several unequally sized groups based on the community’s tradition and history. The largest of these are: the Ashkenazim, whose traditions originate from Central and Eastern Europe; the Sephardim, whose traditions began on the Iberian Peninsula then dispersed across the Mediterranean after the Spanish Inquisition; and, the Mizrahim, whose communities lived alongside the Middle East’s Arab and Persian populations. Alongside these major groups, there are smaller communities such as the Ethiopian tradition.

These ethnic groups are further divided by their views on the heterogeneous Jewish religion and on when one’s family settled in Israel. Each immigration wave brought with it different traditions, experiences, and reacted differently to Israeli life based on their previous countries customs. A traditionalist Ashkenazi Jew differs from a traditionalist Sephardi and a religious post-Soviet Jew has different traditions than a religious Jew raised in Israel. The divides persist to varying degrees across the multitude of religious views, including, but not limited to: Modern Orthodoxy, Traditionalist, Masorti (Conservative), Agnostic, Secular, and even Atheism.

The Arab populations living within Israel are no less unified. Religiously the group is mainly Sunni Muslim, but substantial populations follow the Druze, Baha’i, or various Christian sects. A majority of the population live in Arab towns, but there are also tribal Bedouins residing in their own desert villages and others who live in the traditionally Arabic neighborhoods of major cities. Israel’s Muslim Arab population is among the poorest in the nation, yet Christian and secular Arabs are more likely to possess a college education and have an average income greater than most Jewish demographics. Then there is the question of identity: Palestinian, Israeli-Palestinian, Israeli-Arab, or something in between.

The Factional Poles

Factional divides allow a multitude of parties to thrive in Israeli politics. The 3.25% threshold for parliamentary representation just forces Israeli political tickets into umbrella alliances or factional mergers to allow multiple groups access to the Knesset. Every election sees new Israeli political alliances emerge promising access and failed older ones vanish, but the factional political poles they orbit rarely change. Multiple parties align themselves with the same pole, and voters aligned with that pole move between aligned parties easily. Larger tickets, including Likud, are coalitions of factions which may gravitate around different poles despite the perception of electoral unity.

The Secularizers

Jewish Israeli secularism is not agnosticism or atheism. A secular Israeli Jew often will celebrate Jewish holidays and participate in cultural norms – the affixation of mezuzah for example. Judaism is only a single facet of a secular Jewish Israelis identity. Secularizers oppose policies originating from the Israeli Rabbinate, the Haredi community, or religious-minded politicians. The Secularizers perceive these policies as limits on personal freedom and as favoring the Jewish identity over any other. These views open the Secularizers’ tent to minority religious groups.

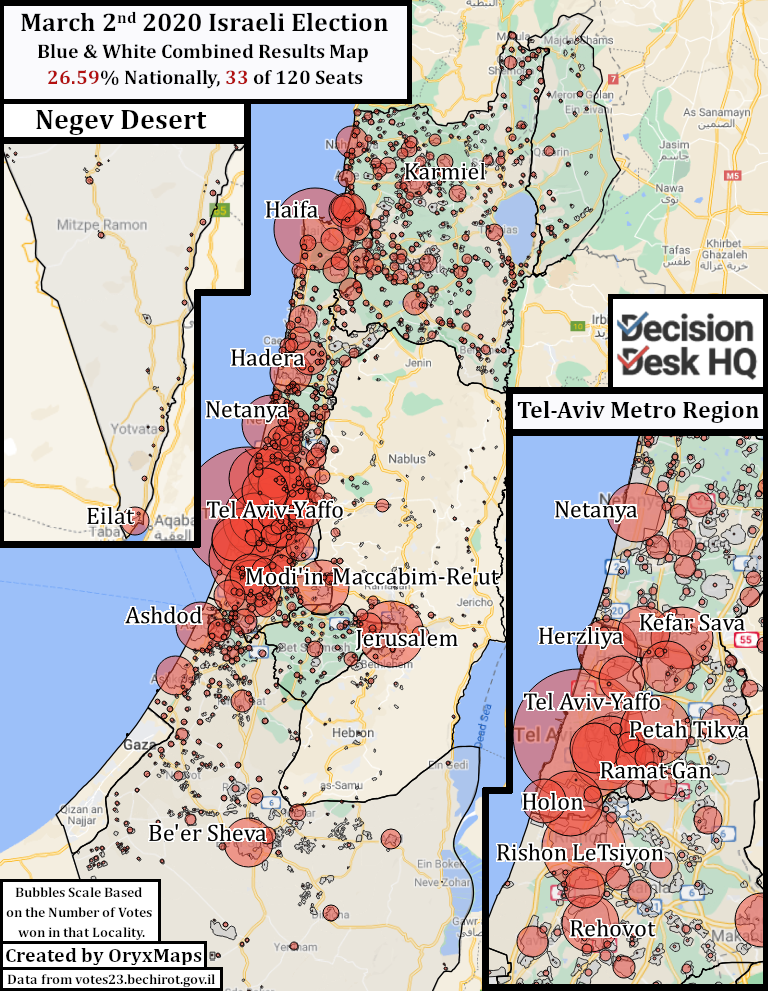

Tel-Aviv, Haifa, and their suburbs along the north coast contain the majority of secularized voters. The cooperative agricultural communities known as kibbutzim are additional strongholds, but contain few voters. Secularizers are more likely to be Israeli natives and their multigenerational Israeli families unintentionally facilitate access to education and employment. This election, the Secularizers align with either Yesh Atid, Blue & White, Labor, Meretz (Greens), or Likud depending on factionalized identities.

The Haredim

Those subscribing to this traditionalist (Ultra-Orthodox in the United States) version of Judaism live separately from mainstream society. Identity comes from the Haredi community and devotion to its ideals. The Haredim have a lower employment rate and a higher birth rate when compared to other Israeli Jews. Most Haredi youth study in yeshiva (Jewish religious schools) which historically exempts the community from Israel’s military draft laws. Haredi communities’ prioritize the freedom to live according to Rabbinic customs. Laws designed to “integrate” the Haredim, such as ending their military exemptions, are viewed as attacks upon the community’s liberty.

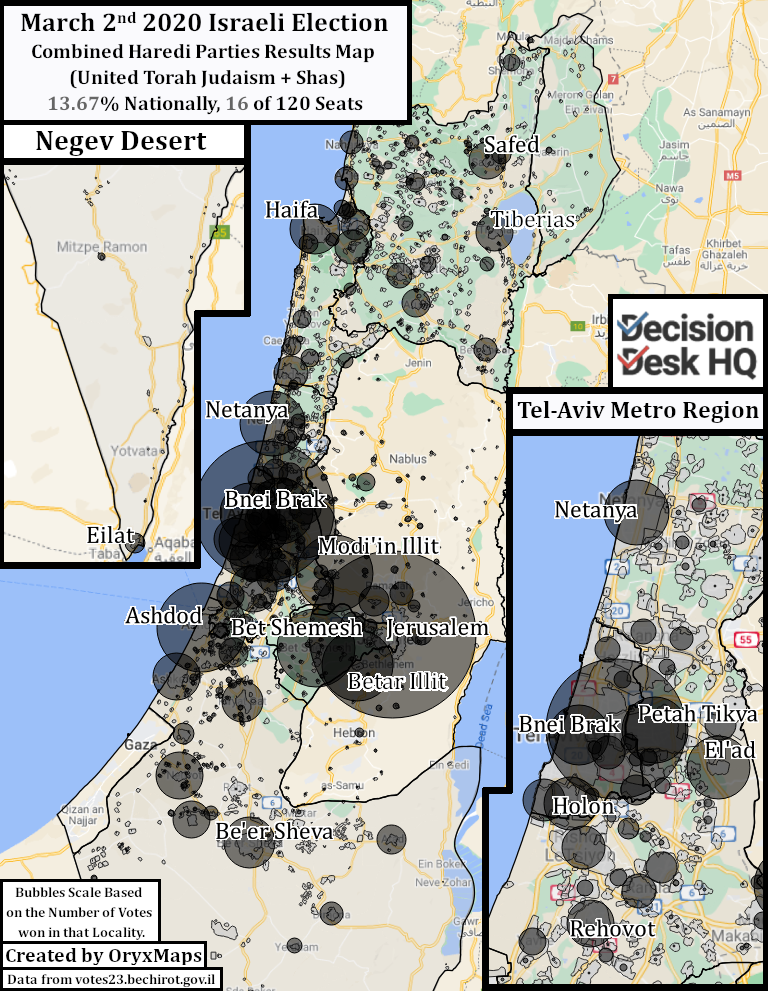

Some of the Haredi neighborhoods hold traditional religious significance, like those in Jerusalem, but others were built to accommodate their different lifestyles. Markets and services in Haredi communities are tailored to their needs, attracting specifically Haredi families and pushing away others. This leads to self-segregation in Haredi settlement patterns. A small number of Haredim vote Likud, but nearly all Ashkenazi Haredi communities vote for the parties under the United Torah Judaism alliance, and nearly all Mizrahi and Sephardic Haredim vote for Shas.

The Pragmatic

Pragmatic or traditional Jews are politically between the Haredim and the Secularizers and defines themselves by rejecting both groups. Sephardic and post-Soviet Jewish groups are the pole’s main constituencies. Individuals support secularist reforms but prefer that reforms are made within the existing Rabbinate-State relationship. The group’s key feature is its commitment to the continuity of the current system, as disruption could end the comparative prosperity this group now enjoys when compared to its ancestors.

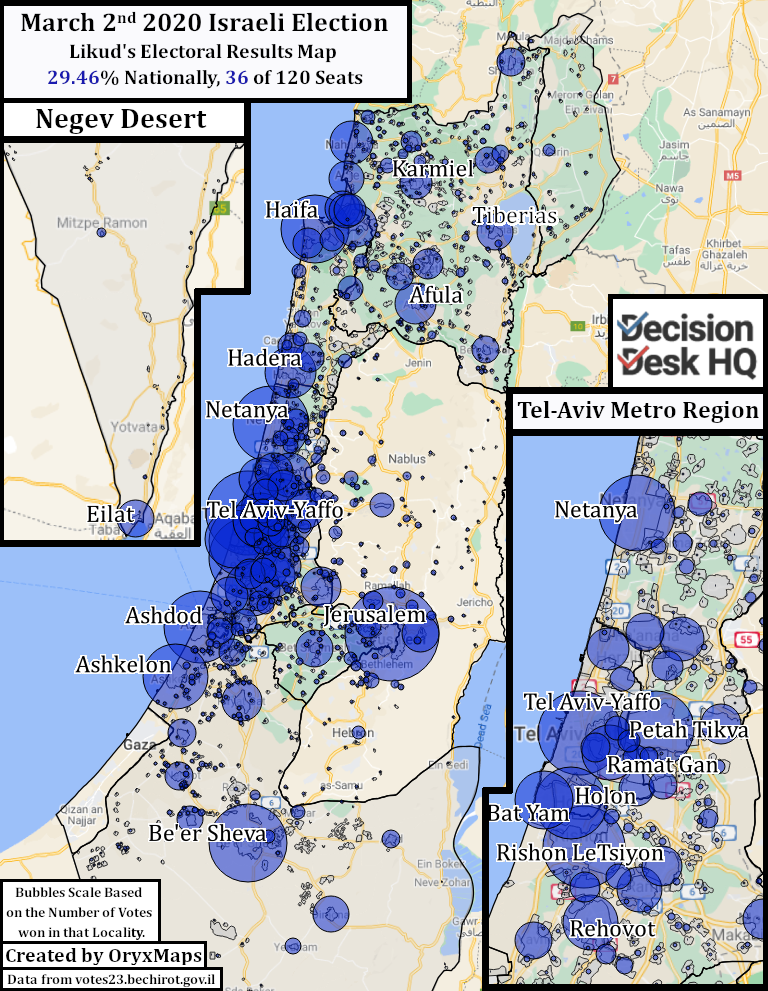

This is Likud’s base but it is not theirs exclusively. Larger opposition parties like Blue & White, between 2019 and 2020, campaign for this same voter pool and Yisrael Beiteinu competes solely for the Russian-Jewish vote. This election cycle former Likudite Gideon Sa’ar is challenging Prime Minister Netanyahu for primacy via his New Hope party. Urban areas like Ashdod—areas developed recently when compared to the north coast and ancient cities—are strongholds of pragmatic traditionalists, along with surrounding suburban developments and periphery villages.

The National Religious

National Religious Jews are not all doctrinaires, even though their political parties align themselves with conservatism. The belief that Israel should be a Jewish State for the Jewish people unites many factions for political cooperation. The National Religious believe in the equality of opportunity for all Israeli citizens. This means ending Haredi privileges and ending restrictions on settlement into land perceived to be Israeli in the West Bank. On the fringes of the National Religious movement is the radical Jewish supremacist Kahanist group.

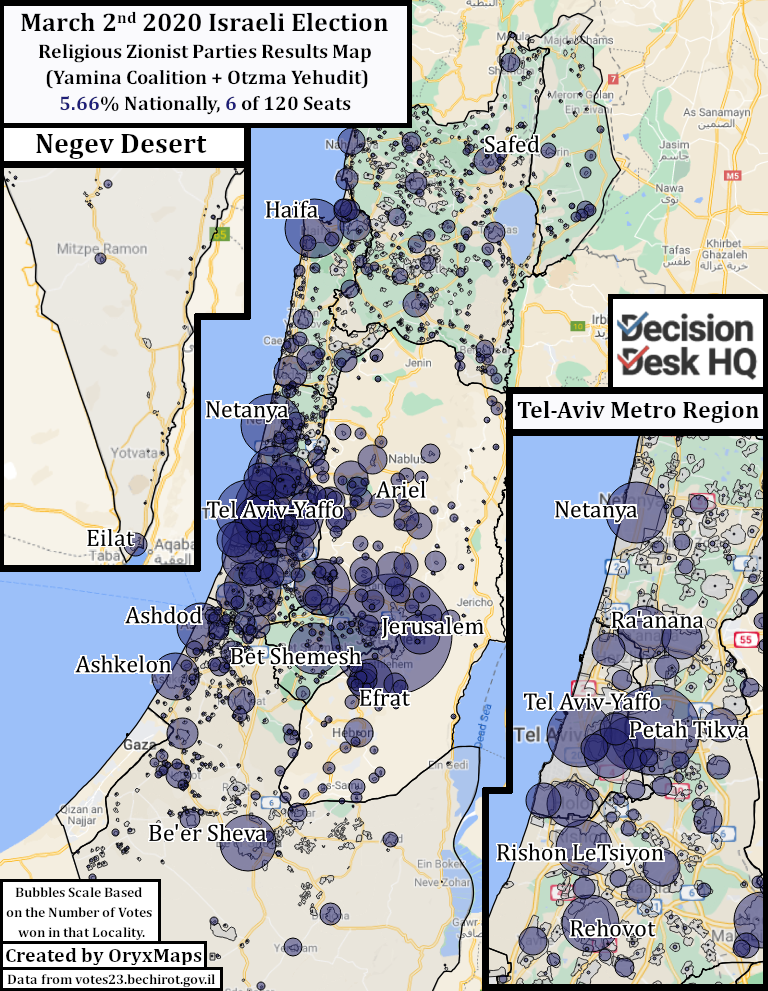

National Religious parties perform extremely well among voters residing within the West Bank settlements. This is because of the movement’s views on protecting and expanding West Bank developments and because National Religious factions claim a birthright and desire to reside in these settlements. Outside of the settlements, the National Religious parties find support among suburban and the more financially well-off migrant communities. Likud historically receives a large portion of the National Religious vote, with fewer votes going to explicitly National Religious parties. This election there are two such lists which contain smaller factionalized parties: Yamina and the Religious Zionists.

The Arabs

Not all Arab citizens of Israel vote for explicitly Arab political parties. Many believe their vote is better used by abstaining from the electoral process. Other factions and subgroups find their interests better served by one of the secularist parties or Likud. Typically, the economically struggling and usually Muslim part of the Arab community votes as a block. Each Arab community perceives and experiences a varying degree of inequality, and the explicitly Arab parties are the only ones committed to correcting these social and economic hardships. Divisions allow multiple parties to run candidates and each offer a different answer to the identity question.

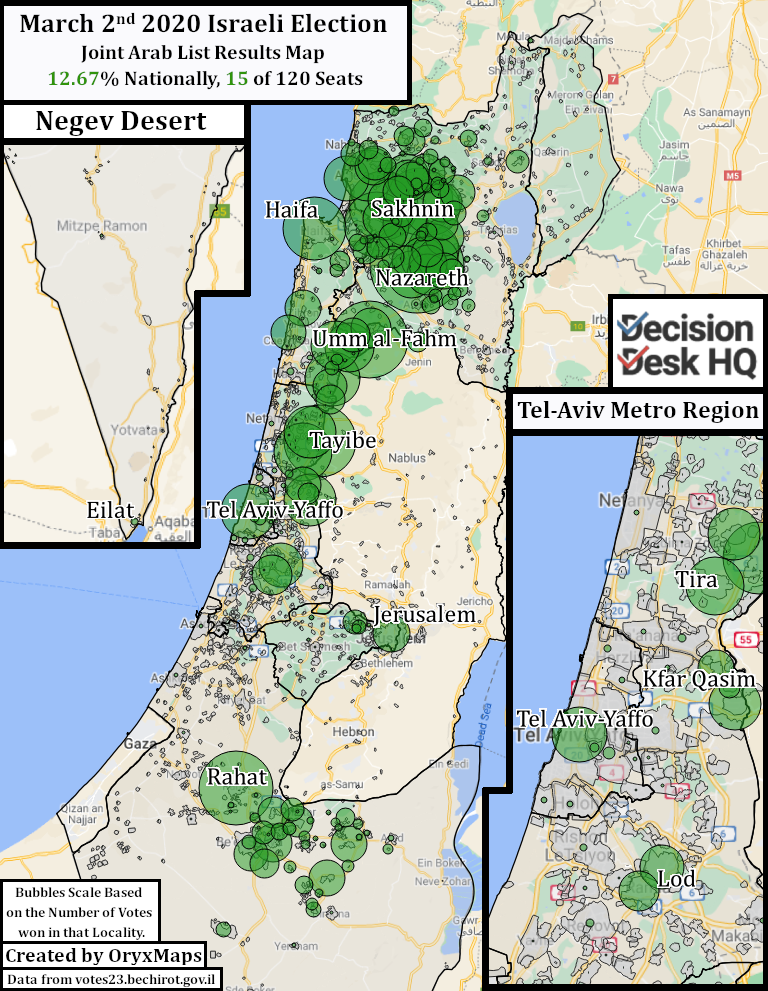

Most Arab votes are in the Israeli North. These are the financially struggling cities and towns that have historically been and remain uniformly Arab. In recent years, the four main Arab Parties have run under a Joint Arab List to maximize representation. This strategy culminated in 2020 when the List won more votes and seats than any combination of Arab parties previously. This year, the Islamist Ra’am party split from the Joint List and now campaigns separately from the Joint List’s Hadash, Ta’al, and Balad parties. Jewish Israeli political parties traditionally have not worked with the solely Arab parties in the Knesset.

The Situation

Every electoral pole is best understood by its view of the Israeli State. No pole is satisfied with the status quo and each believes that they can improve it to enhance individual liberty, equality, or opportunity. The lack of common ground on this question of identity polarizes constituent members. The polar alignment and the unequal distribution of Israeli parliamentary power make it easy for Likud and hard for the opposition to construct a government. A large party like Likud is more likely to act upon pre-election promises to minor parties or voters, has an easier negotiating position, and has access to coercive soft power. This perpetuates the Dominant-Party political system and enables Netanyahu to remain at the center of the Israeli political system.

This cycle, Netanyahu’s ideal government is Likud plus the Haredim plus the National Religious, the same coalition as in years past. Likud will again win the most votes according to polls, but it is an open question whether their coalition will win a majority of seats. The opposition’s ideal government is a combination of the Secularizers, the non-Likud pragmatists, and the non-extremist factions of the National Religious, an alignment with few similarities besides the general idea of reform and opposition to Netanyahu. The potential exists however for neither ideal government to win a majority of seats, necessitating either a messy compromise or the dreaded fifth election.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.