As part of our coverage of the upcoming German elections, in partnership with Europe Elects, we will be running a series of posts to help our audience understand the German electoral system and the state of the race.

In our first installment Tobias Gerhard Schminke, founder of Europe Elects, takes an in depth look at the parties vying for votes and how they may relate to one another in any post-election coalition.

Germany 2021: 101 Level Introduction To An Exceptional Election

By Tobias Gerhard Schminke

Europe is heading towards maybe the most crucial election in several years this month, as Germany elects a new national parliament (“Bundestag”) on 26 September 2021. Germany is not just the largest economy on the continent but is also the most powerful nation in the European Union (EU). Wherever Germany is heading politically, the EU will be shifting towards it as well. German elections on the federal level have always been relatively boring from an electoral enthusiast perspective, but this year is different.

First about German electoral history: Since the end of the Second World War, the electorate has always been relatively stable compared to other European states: the centre-right CDU/CSU party alliance (EPP Group in the EU Parliament), the liberal FDP party (Renew Europe Group in the EU Parliament), as well as the centre-left SPD party (S&D Group in the EU Parliament), dominated the democracy in West Germany. In the East, the SED party ruled the German Democratic Republic (GDR) with an iron, authoritarian fist until it eventually morphed – after democratization – into what is today DIE LINKE (Left in the EU Parliament), a democratic socialist party. Beyond that, over seven decades, GRÜNE (Greens/EFA Group in the EU Parliament) was the only newcomer party that managed to enter the national parliament permanently. In the last election 2017, the far-right AfD (ID Group in the EU Parliament) managed to enter the Bundestag but has yet to prove that they can establish themselves as a permanent force over several legislative periods.

Now, what makes this election so different? The federal chancellor (“Bundeskanzler”) is the head of government and represents Germany in the European council. While (s)he is elected by and constitutionally more dependant on the legislative compared to, for example, the US President, the position comes with significant power (after all, everyone in this world knows Angela Merkel for a reason other than her formidable pantsuits). The chancellor coordinates the government by commanding a majority in – the now to-be elected – parliament. Because CDU/CSU and SPD were always miles ahead of the other parties, only they had a chance to grab the chancellorship. This year, for the first time, GRÜNE has a chance of winning this jackpot. Also, as none of the parties will achieve a majority, they will need to form a coalition government. With the large parties in decline, a three (or four-party if you count CSU separately) alliance might become necessary for the first time in Post-War German history to form a government. Additionally, 9% of voters say in polls that they intend to vote for one of the many minor parties – an exceptionally high value. About a third of this 9% is controlled by the Free Voters (Renew Europe Group in the EU Parliament) party, a centrist party claiming to represent rural communities. Furthermore, there is still a very slim chance that the Free Voters make it across the 5% parliamentary threshold. Also, for the first time since the 1960s, the Danish minority party SSW is hoping to get one seat in parliament. Moreover, it is the first time in post-Nazi Germany that the incumbent chancellor is not running for re-election, which encourages former Merkel voters to reorientate themselves. On top of this mess, voter volatility is higher than ever before, which means we see significant changes in polling on a weekly basis.

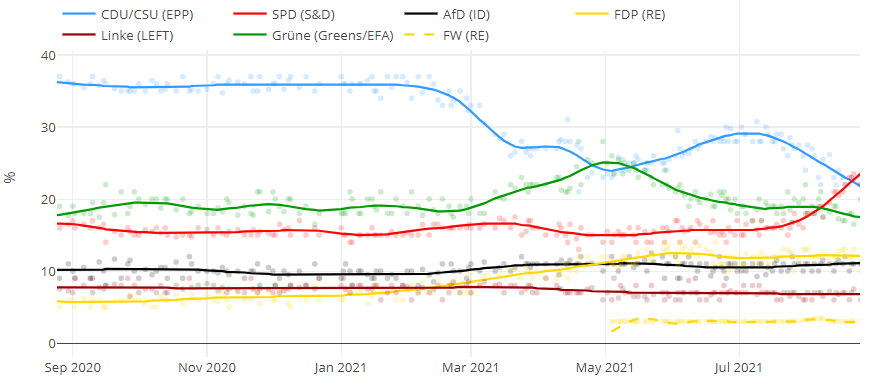

So, what the status of the current parties and who could form the next government with whom? Let’s start here: After 16 years, Merkel decided just to retire. This power vacuum sent her party alliance CDU/CSU into an internal power struggle that subsequently led to the selection of a weak and unpopular chancellor candidate, Armin Laschet. The CDU/CSU alliance, which always dominated Germany’s political scene with election results of over 30 and 40 percent, polled at only 19% in this week’s Forsa poll (2017 proportional vote: CDU with 27% and CSU with 6%). The political significance of a collapsing force, socially conservative and economically centrist, cannot be overstated. The collapse of CDU/CSU leads to the rise of a smaller political force which promises to take Germany on a different path than CDU/CSU – especially if it comes to social issues, taxation, and the fight against climate change.

SPD is the oldest party in Germany. The Social Democrats favour a strong welfare state and are ideologically close to the ideas of the modern-day US Democrats under Joe Biden. The two parties also cooperate in the Progressive Alliance framework. SPD was able to profit from the Merkel party decline, and they are now ahead in all polls with around 26% (2017 proportional vote: 21%). If they managed to form a government under SPD leadership, Olaf Scholz would become the new chancellor. SPD’s recent history has been hallmarked by the divide between the more centrist Social Democrats more left-wing Social Democrats that are more critical of former SPD chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s social policy. Scholz is a centrist and favours a government coalition with GRÜNE and – if necessary, as a third partner – FDP or CDU/CSU. The party leadership and the youth organization of SPD, Jusos, tend to favour a coalition with GRÜNE and – if necessary, as a third partner – LINKE.

Maybe to the surprise of many, the right-wing AfD is not a party that profits from the collapse of CDU/CSU. The party that admires Donald Trump for his border-wall ideas and blunt rhetoric is set to slightly decline from their 2017 result (12.7%) to about 11%. None of the other major parties that command 80% of Germany’s electorate are willing to form a coalition with AfD.

The liberal FDP can profit a lot from the decline of CDU/CSU. This week’s Forsa poll shows FDP at 13% (2017: 11%), which would be one of FDP’s best election results. The term “liberal” in Europe is slightly different from the understanding in the US. FDP, for example, intends to reduce bureaucracy and taxes in this specific election campaign for high-income earners and enterprises. They see education, innovation, and digitalization as key to progress, rather than state intervention. Compared to CDU/CSU, FDP is also more strongly favouring EU integration and progressive on social issues, such as LGBTI+. FDP’s preferred partner for a coalition government is (and has always been in recent decades) CDU/CSU. However, as this option is currently unrealistic to achieve a majority, FDP was open to cooperating with GRÜNE and SPD (but not AfD and LINKE). However, FDP’s leader Christian Lindner has an open distaste for an SPD-GRÜNE-FDP government because of different approaches between FDP and SPD/GRÜNE to taxation and state-interventionism in the economy. However, if CDU/CSU decides to join the opposition due to their poor performance, FDP will not have much choice if they want to enter government. An alternative could be a CDU/CSU-GRÜNE-FDP government. However, this would inconvenience GRÜNE as they would need to accept painful compromises on their core subject – the fight against climate change through state intervention rather than relying on the innovation of the free market.

The left-wing LINKE opposes Germany’s membership in the NATO military alliance and refuses to acknowledge GDR as an “Unrechtsstaat,” which makes it a challenging partner for any sort of government coalition. On the regional level, the party has formed coalition governments with GRÜNE and SPD; the party leadership favours this option for the national government as well. However, first LINKE needs to make sure that they remain part of the parliament as polls show them just above the five-percent threshold (2017: 9%).

The main beneficiary of the swing voter dynamics is continuing to be GRÜNE – even though the party has lost almost half their electorate over the past weeks in polls. Current polls see the centre-left environmentalists at around 16%, up from 9% in 2017. At the beginning of the election campaign, the party hoped to grab the chancellery. Despite the recent decline, the party is open to cooperating with and courted by essentially all other parties, except AfD and more centrist segments of the party have some reservations towards cooperating with DIE LINKE. With only 18 days to go until election day, it remains unclear which government coalition option will eventually end up with a majority. If CDU/CSU decides to bargain to become part of a coalition government will also depend on how disastrous the election result will be. German political culture will make it hard for Laschet to remain in charge of the party or claim the chancellorship if CDU/CSU does not come first – no matter what the government coalition will be. As the polls are volatile and the parties struggle to react to ever-changing majorities, it remains unclear which coalition is the most likely as the parties mostly refuse to rule out options. The following coalitions remain possible:

- A left-wing majority “R2G” (SPD-GRÜNE- LINKE)

- A centrist “Germany-coalition” (SPD-CDU/CSU-FDP)

- A centrist “Jamaica coalition” (CDU/CSU-GRÜNE-FDP)

- A centrist “Kenya coalition” (SPD-CDU/CSU-GRÜNE)

- A centre-left to centre “Traffic Light Coalition” (SPD-GRÜNE-FDP)

Europe Elects projects that the incumbent combination of CDU/CSU and SPD (“Grand Coalition”) has a chance of 35% to receive a majority. Post-election government negotiations between the parties will show which of the creatively named government options will rule Germany until 2025.

Tobias Gerhard Schminke is the founder of Europe Elects (europeelects.eu)

Questions: [email protected]