Israeli voters went to the polls on March 23 for the fourth election in two years, and the electorate once again returned a set of results detrimental to the construction of a majority government. I noted as much in my previous Decision Desk article on the results of the Israeli election. Neither of the two pre-election party alliances commanded a majority in the Knesset (Israeli Parliament), and multiparty polarization seemingly ensured no party had any incentive to betray its electorate and enter a coalition with an electoral enemy. A fifth and final election seemed all but inevitable.

Yet Israel now has a government. Eight parties united by their opposition to former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Likud inaugurated a government that enjoys the confidence of the 120-member Knesset. The coalition agreement survived both the street fighting in Jerusalem between Kahanist settlers and Arab residents, and the conflict between Hamas and the Israeli military. The emergence of a coalition between Jewish and Arab parties ‒ that survived conflict between the two communities ‒ confirms that modern Israeli politics no longer solely revolves around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Israel has a dominant-party system. Likud was the dominant party, and its leader, Benjamin Netanyahu, is at the center of both the system and his party. Likud has gone from commanding unmatched amounts of political influence, favors, electoral legitimacy, and parliamentary experience to almost nothing. Netanyahu’s electoral miscalculations, brinkmanship, and Likud’s decision to spend all available political capital to protect their former Prime Minister from his corruption investigations has brought the opposition to power. Now Likud is vulnerable and Netanyahu is no longer Prime Minister.

Repetition Breeds Discontent

The outside observer only interacts with Israeli Politics through the lens of foreign policy. This fosters an incorrect belief that Israeli Politics is all foreign policy. The only issues perceived to matter are relations with Arab communities at home and abroad, West Bank settlements, security and defense, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This view often follows from a pre-established belief in the correct resolution to the conflict, which then determines the observer’s interpretation of the government. The political reality is not this simple.

Until the 2021 election, Likud and Netanyahu did attempt to reduce every major political issue to a question of religious identity and national security, but not because every issue is a question of national security. Likud and Netanyahu ‘own’ these political issues. Likud wins if an election is a choice between stability with Likud and chaos with the opposition. Likud dominated Israeli politics by answering the security question. Marketing made stability synonymous with “The Right,” and any potential adjustment to this arrangement as “The Left.”

Likud won the debate over national identity. The spectrum of party positions presented by the smaller parties shifted. Electoral viability required compliance with the wishes of the electorate, and parliamentary viability required partial alignment with Likud’s policies ‒ to potentially gain entry into a Likud coalition. The Israeli Labor party lost all relevance. Likud entered 2019 in command of political discourse.

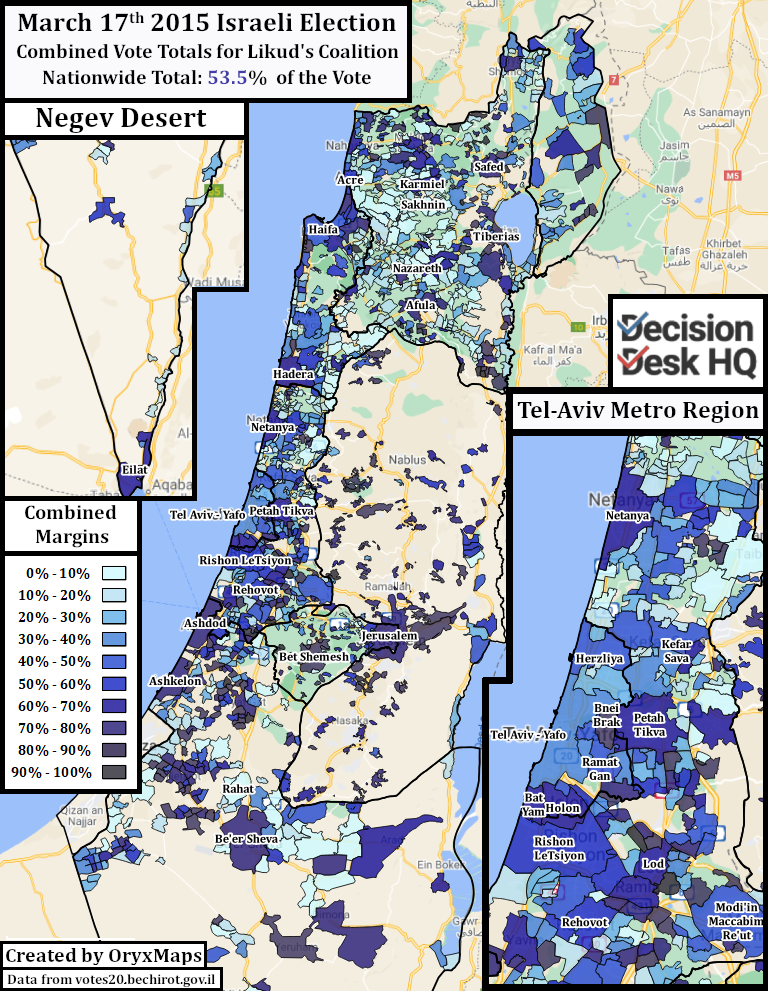

All political parties treated the initial 2019 election as a Likud-led coalition re-election campaign. Likud and various other conservative, religious, and Haredi parties won a majority in 2015. Disagreements between then Likud-ally Yisrael Beiteinu, led by Avigdor Lieberman, and Netanyahu severed the coalition and forced these early elections. Likud and their former coalition members partially campaigned as a block, intending to resume the previous government. The aligned minor parties approved of the leeway Likud gave them on pet issues like religious policy, Haredi cultural requests, and new settlements. In exchange Netanyahu received wide latitude on issues outside of these fields. This included the Prime Ministerial immunity laws Netanyahu now needed to avoid the state corruption investigation opened against him in 2016.

Likud’s 2019 campaign focused on the security question and attempted to tie the opposition to the Arab parties, the party’s strategy from previous campaigns. The opposition, now led by the secularist Blue & White unity ticket, chose not to debate national security. Blue & White only brought up security to prove that it would not radically diverge from Likud’s electorally successful program. The opposition preferred to focus on the coalition Likud wanted the voters to re-elect. They highlighted what many Israelis saw as Haredi privilege, and the seemingly authoritarian laws Netanyahu desired to preserve his control. The opposition’s platform included Likud-style policies on a variety of lesser issues, an acknowledgement that association with “The Right” was necessary for electoral success. Blue & White preferred a “Grand Coalition” government between them and Likud, with Blue & White leader Benny Gantz and Netanyahu rotating the Prime Minister’s office. This government would preserve the taboo on the Arab parties.

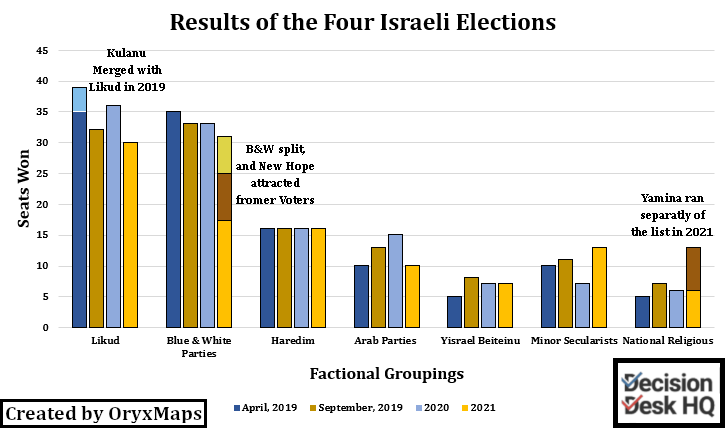

Likud and Blue & White effectively tied, each winning 35 seats. Likud’s previous coalition government commanded 65 seats and appeared poised to return to power. Lieberman however quit the coalition, citing growing personal hostility to Netanyahu and his long-standing enmity towards the Haredim. Without Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu there was no longer a majority in the Knesset for another Right-Religious coalition. The parties now opposed to Netanyahu’s incumbent coalition won more popular votes than the parties aligned with Likud, and the two camps each had 60 Knesset seats. Lieberman called for a “Grand Coalition Plus,” which would include Yisrael Beiteinu, Likud, and Blue & White. This government however would not pass the desired immunity laws and leave Netanyahu vulnerable to prosecution. The caretaker Likud government then dissolved the Knesset and called new elections.

Israelis voted for a second time in 2019. The various parties’ confrontational campaigns framed the election as a decision of who the voter despises more, the Haredim or the Arabs. Voters elected a majority opposed to Netanyahu’s coalition, but it was an unworkable majority given the mutual distrust between the Arab parties and Lieberman. A third election became necessary after another doomed attempt at building the “Grand Coalition Plus.” Netanyahu’s quest for personal power and prominence prevented consideration of anything but his ideal government, even though Likud had once worked with the individual politicians who now led opposition parties. The third election did not alter the underlying arithmetic. Once again Likud and her minor party allies were unable to build a majority, but changes in voter turnout benefited Likud and the Arab parties.

The Coronavirus pandemic necessitated postponing plans for a potential fourth election. Repeated elections wore down the intransigence of each parties’ political positions, and the immediate necessity of the coronavirus threat demanded compromise. Likud, the Haredim, Labour, and the half of Blue & White more aligned with Gantz than his ally Yair Lapid built an “emergency” coalition. This was a temporary agreement designed to collapse with the return of normalcy, and kept all constituent members away from the offices and privileges they actually desired. As the Israeli population vaccinated, infighting and enmity undermined the government. It once again became necessary to dissolve the Knesset and hold a fourth election in March 2021.

What makes these Results Different from other Results?

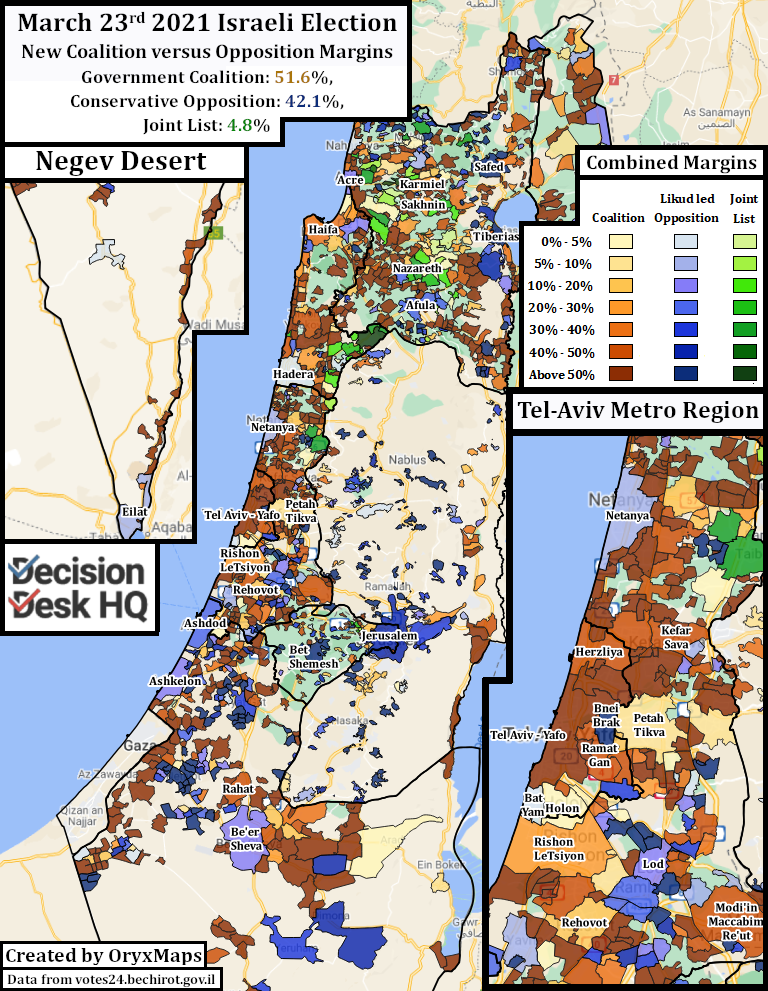

The results of the fourth election in two years resembled the preceding three. Likud won the most seats by far, but this matters little in a parliamentary arena. A majority voted in opposition to Netanyahu’s predetermined coalition, but an easy, alternative coalition remained out of reach. The combined opposition parties actually polled worse than in two of the three preceding elections.

Only the context of the three previous elections can explain why after three cycles of failed negotiations, compromise succeeded in 2021. Four elections softened parliamentary partisanship and, this time, many major parties contemplated deals once considered unthinkable. Repeated contests taught both the parties and their voters exactly what parts of their platforms mattered, what didn’t, and what they were up against.

Labor finally dropped the façade of a national party competing for leadership and adopted a targeted message for an activist electorate. The Blue & White electorate had split into three parts: the older Yesh Atid party under Lapid, the Blue & White remainder under Gantz, and the New Hope party under Gideon Sa’ar. Each offered a different theme: Lapid adopted a no-Netanyahu opposition line; Gantz still left open the possibility of the “Grand Coalition”; and, Sa’ar offered hope for a Likud-like government without Netanyahu. The Haredim prepared to set aside their principles and accept whatever government Likud needed to maintain power. The minor, National Religious and Kahanist parties came together to prevent electoral vote-wasting and ideally provide the Likud coalition the necessary seats. Yisrael Beiteinu and Lieberman abandoned any hope of cooperation with Likud, and now would support any coalition without Netanyahu or the Haredim. However, the three most important changes came from Yamina, Likud, and the Arab parties.

Yamina (previously under the names New Right or Jewish Home) and its leader Naftali Bennett were a reliable Likud ally until 2020. Bennett’s party was just one of many smaller parties appealing to the National Religious and settler communities. The party failed to cross the 3.25% electoral threshold when it ran independently in 2019 and thereafter joined a unity ticket in the two subsequent elections to maximize electoral opportunity. This unity ticket refused to join the 2020 emergency coalition. Bennett stated opposition to letting Blue & White control the Justice Ministry, but politically the smaller National Religious parties found themselves isolated and lacking any influence in the oversized emergency government. Bennett discovered during opposition that an anti-Likud message gave the party the voice he desired. Yamina occasionally polled as the second-largest party during the pandemic. The number of projected Yamina seats declined as parties began their 2021 campaigns and voters returned to their partisan camps, but the confrontational message allowed Yamina to campaign on its own and hinted at future possibilities.

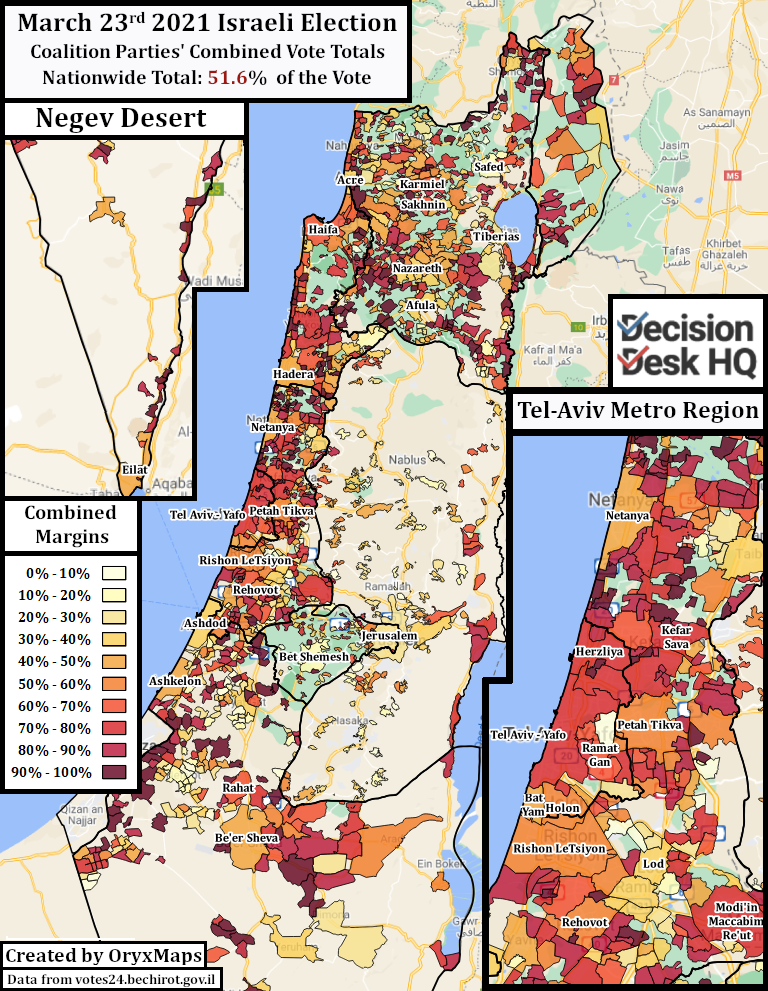

Equally dramatic was the abrupt shift in Likud’s relationship towards the Arab electorate. The Arab Joint List won more seats in 2020 than any previous combination of Arab parties, continuing a three-election trend of progressively increasing Arab voter turnout. There was legitimate fear among Likud strategists that surrendering this growing electorate would finally give the opposition the numbers needed to form a viable coalition. Netanyahu additionally found a new potential ally for his Right-Religious alliance within the Arab opposition. The United Arab List (better known as Ra’am) – formerly a constituent party within the Joint List Alliance (similar names, different political groups) – and its leader Mansour Abbas were willing to support a Likud government in exchange for much-needed investment in Israel’s majority-Muslim communities.

Breaking with its past strategy, Likud lowered its electoral cordon around the Arab parties and ended its political stigmatization of the Arab electorate. Likud used the political capital gained through the diplomatic “Abraham Accords” to launch an Arabic ad campaign in majority Arab communities. Netanyahu and Abbas openly talked about cooperating to deliver massive state funding for disadvantaged majority-Muslim Arab cities. Ra’am left the Joint List to campaign on a message of pragmatic development, even if it meant saving Netanyahu’s personal career. Likud’s strategy had two potential outcomes: separating the Arab parties could cause Ra’am to fall below the threshold and give Netanyahu’s preferred alliance a majority of valid votes, or Ra’am could enter the Knesset and offer parliamentary support to Likud’s government. This strategy yielded four independent Ra’am parliamentarians openly referred to as an undecided kingmakers by the media, an increase in the Likud vote from approximately 0% to 4% in overwhelming Muslim Arab communities, and the end to Arab parties cultural and parliamentary isolation.

Yet, this strategy was an electoral blunder. The Jewish-supremacist Kahanists and extreme Religious Nationalists in the Religious Zionist party refused to vote for an Arab-assisted Likud government. Ra’am refused to support any government with support from said extremists. The two potential Netanyahu allies were irreconcilable. Bennett canceled negotiations with Netanyahu when a coalition became mathematically unfeasible, ending all paths to a Likud government. Likud’s decision to normalize Arab participation in government finally opened the door for a non-Likud coalition. The opposition parties had fewer qualms about breaking old taboos against Arab participation, and it was now culturally acceptable for the parties to pursue this potential alliance. Lapid officially announced he had formed a coalition with Yamina, Ra’am, and the secular parties on June 2, the last day of his legal negotiating period. This government confirmed its majority support on June 13 by a 60 to 59 vote. The one abstention was planned by a Ra’am parliamentarian as a compromise between principles and access to power, and certain members of the Joint List planned additional abstentions if there were any last-minute surprise defections.

The Tenacity of the Ideal

Likud voters did not incite the ethnic conflict that began in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah on May 6. Nor did the Likud-led government initiate the latest conflict with Hamas in Gaza. A good politician however knows how to leverage a crisis to his advantage. Negotiations between Yamina, Ra’am, Lapid, and the rest of the opposition “Change” block were close to a final coalition agreement when these conflicts escalated into crises. This was the perfect opportunity to divide the fragile opposition alliance and reinforce Likud’s historically winning message of security. Netanyahu conflated his personal goals with the national interest, and let domestic policy drive foreign policy.

Opposition coalition negotiations appeared to break down because of the conflict. Ra’am refused all negotiations until stability returned. Bennett and Yamina deemed it impossible to enter government alongside an Arab party with Israel in crisis. As a fallback, Yamina and Likud negotiated an electoral pact if a fifth election became necessary.

Yet the stalled negotiations resumed after the ceasefire with Hamas took effect. These negotiations were successful. This resulting coalition does not make sense if one views the region through the lens of a black-and-white good-versus-evil dichotomy. How could Ra’am, an Islamist conservative Arab party, enter government with numerous other Jewish parties just days after the IDF shelled Palestinians in Gaza? How could Yamina, a party that earned 14% of the settler vote, accept support from the supposed ‘enemy?’

First, this dichotomous view fails to reflect the developments of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and how those developments affected the people of the region. The first era of both the conflict and the Israeli state was one of conflict with the surrounding Arab nations. It lasted from about 1948 to the late 1970s, and Labor (and its predecessor parties) dominated Israeli politics. The second era lasted until the 2010s and is characterized by grassroots Palestinian insurgency and terrorism best symbolized by the Intifadas. Likud and Labor polarized the country for political control during the second era, a fight that Likud eventually won. The contemporary era is characterized as one of comparative stability achieved through Israel’s military strength. Hamas is contained by Israel’s Iron Dome, the Fatah Palestinian Authority government lacks popular legitimacy, and Arab Muslim states have normalized relations with Israel over shared enmity towards Iran.

As the conflict changed, new generations of Israelis and new waves of immigrants came to understand and perceive the conflict through present events. Preceding generations’ experiences helped shape and contextualize their own understanding of changed conflict. This led to electoral generational divides. Likud for a long time did better among younger voters and their rivals among older voters, a dichotomy that only changed comparatively recently. Likud’s strategy of dividing and delegitimizing the Palestinian cause worked perfectly, but these tactics reduced the efficacy of the party’s security platform. A generation has entered the electorate with little experience of the dangers that attracted their parents to Likud.

Second, the conflict and peace process are no longer the most prominent electoral issue in Israeli politics. With stability and an absence of direct conflict, voters and politicians do not need to immediately confront the larger Palestinian question. Other social divisions between factional communities are increasingly relevant to voters and the new government is built to confront these divisions.

The Haredi community has forced Israeli public society to accommodate their traditional lifestyle, with military exemptions, low workforce participation, Sabbath work and travel restrictions, and exclusive education curriculums. Secular parliamentary factions wage political battles to standardize the community with the rest of society, and the Haredi parties desire to protect and expand these accommodations. Muslim Arab cities remain poverty traps with little investment or development. The Arab parties wish to correct for this imbalance, but the racist Kahanists and their allies demonize and scapegoat the Arab community. Liberals argue Netanyahu’s attempts to avoid his corruption investigation and abuse of state power is creeping authoritarianism and an undermining of democracy, others argue Likud must do what it needs to perpetuate stability. Repeated elections only deepened these divides, polarized the factional parties, and reoriented voters to view opposing factions as a greater threat to future stability than any exterior foe.

The Road Forward

Israeli society considers democracy paramount. Even the racist and Jewish-supremacist Kahanists commit themselves to the idea of electoral democracy, but without any Arab voters. Liberal, individualistic policies often command large electoral support. These issues are rarely polled, but one such issue with data ‒ same-sex marriage ‒ has broad support in Israel. Recent surveys found between 58% and 78% of the country supporting same-sex marriage depending on the wording of the question. A majority of voters from all parties, except the Haredim and the Arabs, support legislation. Haredi influence over a Likud-led government prevents the issue from ever entering parliamentary debate in a Likud-led government.

This “Change” coalition may or may not pursue same-sex marriage, but this polling data offers a perspective into the electorates support for equalizing liberal reforms. These civic reforms are supported by the majority of the population, but Likud politicians either opposed their implementation or never viewed them as politically advantageous. Some issues do not have the support of Ra’am, but if the issue is brought to a vote, then a floor vote would likely find support among individual parliamentarians. The Change coalition also seeks to restore and solidify civil society and Democratic order to prevent another Netanyahu. Policies like Prime Ministerial term limits and banning parliamentarians under legal investigation from holding the executive position explicitly target Netanyahu, but they are popular among the wider electorate because they check future abuses of power.

Bennett and Lapid lead the new coalition government. The two leaders intend to rotate the Prime Minister’s office. Bennett serves first until September 2023, at which time Lapid will take over. Until that time Lapid will serve as the powerful Foreign Minister. Lieberman and Yisrael Beiteinu have the Treasury and Financial portfolios, which have significant control over the lives of Lieberman’s Haredi rivals. Gideon Sa’ar of New Hope starts out with the Justice Ministry, and Blue & White’s Benny Gantz leads Defense. If the coalition survives to the date of rotation, then Bennett will assume the Interior Ministry, Sa’ar would move to the Foreign Ministry, and Yamina will take over the Justice portfolio.

The coalition has nine female ministers, a first in Israeli politics. Labor leader Merav Michaeli gets the Transportation portfolio, Yamina’s number two Ayelet Shaket leads the Interior Ministry, and former Meretz (Green Party) leader Tamar Zandberg is Environmental Protection minister. One additional female parliamentarians from New Hope, two from Blue & White, and three from Yesh Atid hold the Education, Science & Technology, Immigration & Integration, Economy, Culture, and Social Equality ministries. Openly gay Meretz leader Nitzan Horowitz will lead the Health Ministry. Arab-Israelis Issawi Frej of Meretz and Hamad Amar of Yisrael Beiteinu lead ministries, alongside Pnina Tamano-Shata of Blue & White, an Ethiopian-Israeli.

Ra’am got what it wanted from the eight-party alliance. The impoverished Arab sector will receive the equivalent of $16.3 billion to develop and modernize Arab cities, fix decaying infrastructure, and fight the violence and organized crime that has taken root in Arab cities. The coalition plans to incorporate several previously unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, and change the construction laws to allow Arab developments independent of state approval. Ra’am’s strategy copies the Haredim, who have long used this type of ‘pork-barrel’ politics to bring patronage to their communities.

The Haredim are now out of, and isolated from, the government. Opposition to Haredi-favoring laws binds the Change coalition partners together. Some Haredi Rabbis said Lieberman’s appointment as finance minister amounts to a declaration of war against the community. Lieberman intends to cut subsidies for the Haredim and implement mandatory job-training programs in all Israeli institutions that receive state funding. The goal of these carrots and sticks is to induce the under-employed Haredi to enter the job market and the wider economy.

Additional secular policy goals may include reimplementation of the Haredi draft law, Saturday bus services, egalitarian access to the Western Wall, and allowing civil marriages through the state and not just the various religious bodies – including the Haredi influenced chief Rabbinate. This coalition perceives that political and social influence have long allowed the Haredi community to live under a different social contract than the rest of Israeli society. The secular parties, united in the Change coalition, may have finally found the political capital to legislate that all Israelis, regardless of their faith or customs, have responsibilities tied to citizenship.

Bennett and his Yamina party officially hold the Prime Minister’s office, but their position is weaker than it appears. Yamina had the power to demand prominent government positions because it was the weakest link in the Change coalition. Lapid offered Yamina generous government portfolios to ensure their cooperation and bind the party to the government, despite Yamina only providing seven seats on paper ‒ then six after a defection. Bennett taking the Prime Minister rotation first is the largest of these concessions made by the other parties. Bennett leads, but he is beholden to his secular and reformist coalition allies. The coalition has no plans for new West Bank settlements, despite Yamina’s non-insignificant support among the settler population. Bennett cannot govern as a National Religious Prime Minister; he is a conservative face on the Change coalition.

The inconsistencies between Yamina and her allies seem destined to eventually lead to deterioration. The Change coalition members recognize that once Netanyahu is permanently removed their alliance loses a common foe. The members seem prepared for this potential result and may want it. Removing Netanyahu decapitates Likud. The party has spent its political capital protecting its leader. Likud has no heir apparent and the party’s elected politicians are either Netanyahu lackeys or ladder-climbers aligned with the dominant party. The former Prime Minister’s apparent intention to remain at the head of Likud until the result of his corruption investigations does preserve the Change coalition’s bogeyman. It also denies any other Likud politician a platform to prepare the party for a future without Netanyahu.

The unspoken goal of many Change coalition parties is to use their time in government to build an attractive brand. Likud’s electorate disagrees with many of the policies advocated by the party’s preferred coalition, but they stayed loyal to Likud because of issues related to leadership, stability, security, or historic identity. Likud can no longer satisfy their electorate and their voters are potentially up for grabs. If no savior emerges then modern Likud could be forced on the electoral path once tread by Labor. A large party cannot hold its constituent factions together if there is no potential for rewards from government participation. Yamina and Yesh Atid both hope to force the issue and become Israel’s new dominant party. A future election in a reoriented political system offers the potential for greater parliamentary powers than those available within an eight-party government. These will not be immediately visible changes and will take time to emerge in polling. Changes are not guaranteed to go in one direction, many parties will benefit if Likud cannot handle a future without Netanyahu. Realignment is impossible to predict, but two years of Israeli political paralysis and stagnation appears to be finally at an end.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.