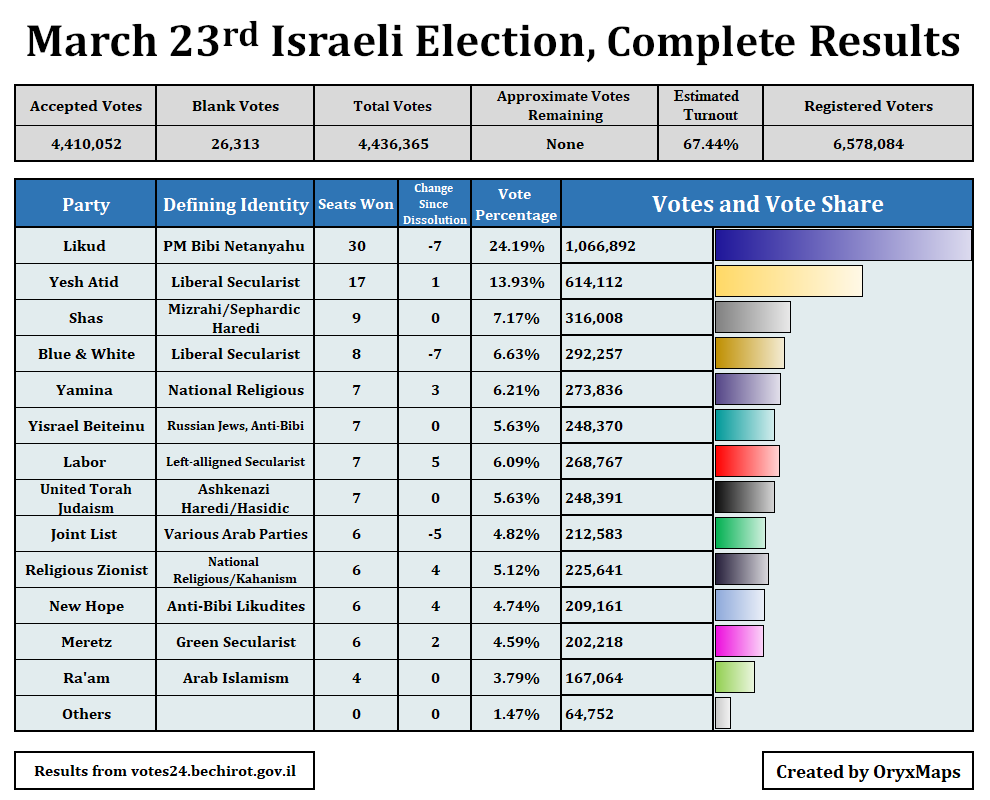

Israel went to the polls March 23rd for the fourth time in four years. Consistent with the previous three elections, no prearranged block of parties won a majority of the 120 seats in the Knesset. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu‘s preferred parties won 52 seats, and his Likud party won 30 seats – the most of any party. The parties elected on a platform of opposition to Netanyahu won 51 seats. Yamina, a National Religious coalition that broke with Netanyahu in 2020, won seven seats. The Arab Joint List’s three constituent parties and Ra’am, a fourth Arab party, won the remaining ten seats. Parties theoretically opposed to Netanyahu received a majority of seats but cooperation is elusive.

Voter preferences barely changed between this election and the previous election in 2020. Significant compromise is once again needed to form a new majority coalition and avoid a fifth election. Repeated elections weakened factional intransigence, but this election’s results demand greater compromise than past contests.

Polarized Voters

The previous articles and newsletters in this series described how Israeli political factions orbit around five polarized political poles: Secularizers, Pragmatists, National Religious, Haredim, and Arab parties. The year-long gap between the 2020 and 2021 Israeli elections shuffled the political landscape and party viability: The Blue & White umbrella ticket split into those previously part of Yesh Atid and those supporting party leader Benny Gantz; Yamina entered opposition and briefly polled at over 20 seats; minor National Religious and extremist parties united into the Religious Zionist party; Gideon Sa’ar left Likud and founded New Hope to challenge Netanyahu’s dominance; Ra’am split from the Joint Arab List.

These party changes did not fundamentally alter the political poles. The Haredi parties won the same 16 seats as in 2020. The non-Haredi parties that support returning Netanyahu to office – Likud, the Religious Zionists, and potentially Yamina – received 43 seats to their previous 42. New Hope won votes from those previously aligned with the Gantz side of Blue & White; and when added together with Yesh Atid, the three parties won two fewer seats than the old umbrella ticket. Yisrael Beiteinu’s seat count did not change.

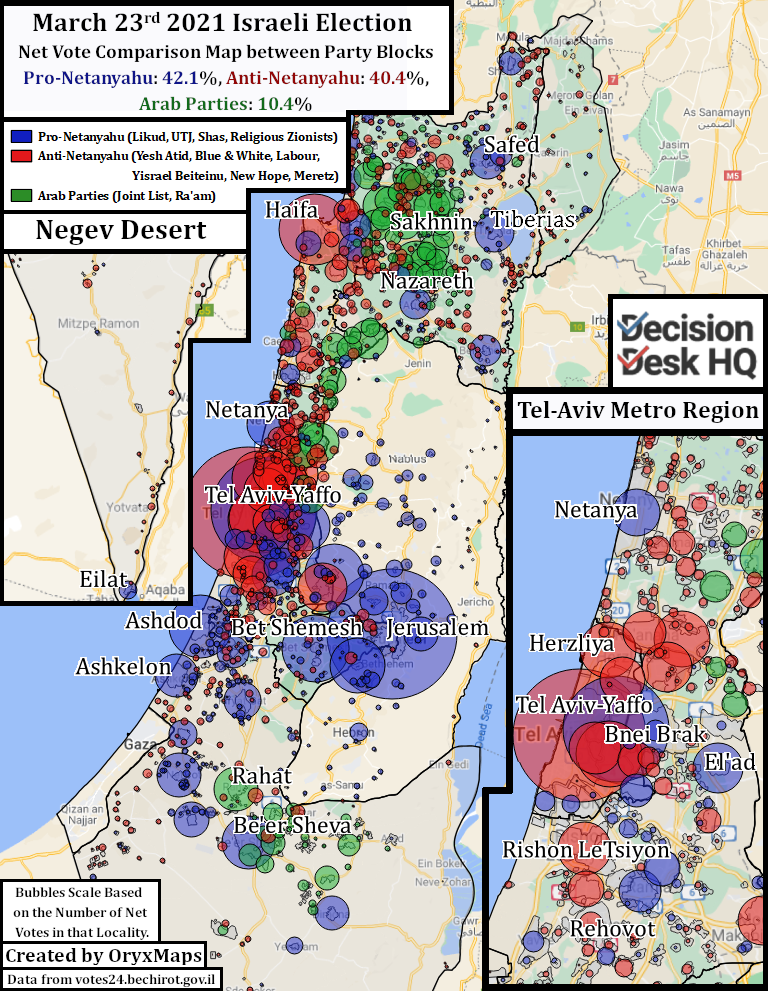

The Arab parties’ political fortunes changed dramatically when compared against the other political poles. The strength of the Arab political pole fluctuates each election based on the Arab community’s perceived importance of Knesset representation. Arab voter behavior differs from their Jewish counterparts because of their political isolation from the mainstream Jewish parties. This election approximately one-third of Arab voters who participated in 2020 do not appear to have voted in 2021, though the turnout decrease was unequally distributed. Turnout varied in Arab areas, from less than 50% to 90% of previous votes. The Arab vote additionally fractured from its near-monolithic support for the Joint List in 2020. Likud picked up voters in Arab localities, but their support mostly drew from the limited pool of Arabs who did not vote for the Joint List in 2020. The Secular Jewish parties – Yesh Atid, Blue & White, Yisrael Beiteinu among the Druze, Meretz, and Labour – were the main beneficiaries of 2020 Joint Arab List voter defection. Meretz and Labor benefited from the collapse of both the 2020 Joint List vote and the 2020 Blue & White umbrella; the parties gained a combined six seats from their previous seven in 2020 when the two parties ran together, bringing their total to 13. Ra’am, who split from the Joint List before the election, won four seats and the Joint List won six.

Only one seat moved to parties that prefer a Likud coalition from the opposition. The majority of voters remained loyal to their preferred political pole; if a voter moved, it was to another party orbiting that same pole or to an adjacent one.

Coalition Stagnation

The voters remain polarized, but the parties took steps to avoid another electoral stalemate. Major party actors compromised their political expectations compared to the previous three electoral contests. Avigdor Lieberman, the leader of Yisrael Beiteinu, previously committed his party to a grand Unity Coalition with the Blue & White alliance and Likud. Now, he acknowledges that the only way to remove the Haredi parties from power is to join with the minor Secularist parties. Yamina left Netanyahu’s coalition and theoretically would back both an opposition and a Likud government if either had the numbers. The minor National Religious parties compromised and agreed to work with Kahanist extremists if it meant fewer votes were lost to the (3.25%) threshold for Knesset representation. Benny Gantz supported the emergency unity government of 2020 even though it fragmented Blue & White and empowered Netanyahu. Gideon Sa’ar attempted to pull away some Likud voters to give a coalition of Jewish opposition parties a majority.

Two opposing alignments of entirely Jewish parties leaves the Knesset in a peculiar situation: if no defectors are available then the Arab parties become kingmakers. Whole party defections are unlikely because the unifying feature of both factions is their commitment or opposition to Netanyahu personally. If Netanyahu left Likud to a successor, then every opposition party could work with Likud depending on which other parties join the hypothetical coalition. The only party who presently could be convinced to work with a Netanyahu-led Likud is Ra’am, an Islamist Arab party. Yamina and the Religious Zionists however have categorically refused to work with any Arab party, and Ra’am likewise has refused to support any government that includes the Religious Zionists and their Kahanist allies. Any simple Netanyahu-led or opposition government is impossible.

The opposition alignment of Yesh Atid, Blue & White, New Hope, Yisrael Beiteinu, Labor, Meretz, the Joint List, and Ra’am has a tentative majority thanks to Arab and National Religious animosity, but cooperation will not be easy. Yair Lapid, the leader of Yesh Atid, is negotiating with the seven other parties in an attempt to inaugurate an anti-Bibi coalition. This government requires Lieberman and Sa’ar to decide that their opposition to the Arab parties is more flexible than their opposition to Netanyahu. Potential intransigence may have weakened when Likud courted Ra’am and normalized the prospect of Arab parties supporting an Israeli government, unintentionally shifting accepted political norms in the opposition’s favor. Lieberman, however, has refused to work with the Arab parties in the past and an agreement between distant poles is unlikely. Coordinated cooperation between eight parties is hard, but the task is near-impossible in a factionalized system.

Defections alternatively can break Parliamentary deadlock. Likud possesses all the coercive carrots and sticks that come from its position as the largest party in Israel’s dominant-party system, and therefore can incentivize defections to support a Netanyahu government. Party defections are unlikely because the two most attractive defectors, Gantz’s Blue & White and Sa’ar’s New Hope, personally benefit from opposing potential cooperation. Netanyahu could entice two elected members of the Knesset to personally defect from the opposition block and support his government in exchange for legislative perks. A defer majority though depends upon Yaminas assistance, and there is no guarantee that Yamina will support a Netanyahu government. The party publicly opposes all of the hypothetical government coalitions and hopes the negotiations develop in a way that allows Yamina to carve off a portion of the Likud electorate.

The Unattractive Alternative

There is an electoral consensus to avoid a fifth repeated election, yet the rational behavior of each parliamentarian places Israel on an unavoidable trajectory towards another contest. The National Religious and the Arab Parties swore off any cooperation with each other, the nationalist side of the anti-Netanyahu opposition likely refuses to back a government supported by the Arab parties, the parties are divided on the issue of Netanyahu personally, and the electorate remains polarized. If there is a fifth election it will likely be the last in this cycle of electoral paralysis.

The first development is the solidification of the party groupings based on their opinions of Netanyahu. Even if the Knesset cannot consolidate a majority coalition, there remains the possibility of targeted legislation passed with the intention of barring Netanyahu from office. This is possible because a majority of Knesset members agree on opposing Netanyahu even if they cannot agree on much else. Lieberman has expressed interest in putting forward laws that require Prime Ministers under indictment to resign and laws that limit the number of terms a Prime Minister can serve. Both explicitly bar Netanyahu from officially campaigning as Likud’s Prime Minister candidate because of his corruption investigation. These laws would hypothetically be repealed if Likud’s coalition won the potential fifth election.

By July 5th the Knesset must elect a new Israeli President. The President is largely a ceremonial Head of State role. The office however commands significant soft power, especially when it comes to coalition construction. The President is elected by a secret ballot of the 120 Knesset members and must win a majority of the votes. If no candidate receives 61 votes then the least viable candidates are progressively eliminated in rounds of voting, until one nominee wins a majority. The current President is Reuven Rivlin, a former member of Likud who distrusts Netanyahu. The Presidential office is a large carrot for barter in coalition negotiations. It is also potentially a partisan office if stacked in preparation for a fifth election. Netanyahu’s absence from the list of candidates will weaken opposition unity and likely result in a ideological vote. Netanyahu could arrange for himself to assume the office to escape his partisan detractors, but he would be handing power over Likud’s parliamentary alliance to a subordinate, making this option unlikely.

Israel has continuity of government laws. When a government loses the confidence of the Knesset, its ministers do not resign: they maintain their positions until there is a new governing coalition. These laws preserved Netanyahu’s 2015 coalition during the period between 2019 and 2020. They now preserve the emergency unity government, and will continue to preserve it if a fifth election is needed. An important condition of the unity government is the Prime Minister rotation agreement. Netanyahu started as Prime Minister with Gantz the titular Alternate Prime Minister, but the two would swap roles after 18 months. The emergency unity government may have officially collapsed before Gantz swapped positions with Netanyahu, but the continuity of government laws will preserve their agreement if there is no governing coalition before November. Gantz would then assume the powers and responsibilities of that office. A constitutional crisis looms if there is a fifth election and Likud attempts to block or bureaucratically ignore the agreed transition.

Each of these three possible developments on their own has the potential to reshape Israel’s political impasse. Each could influence turnout among various factions and move marginal voters, reducing the likelihood that a fifth election results in another stalemate. Each of these possibilities leads to many different outcomes, all of which could adjust the coalition math. Likud was unchallenged when the party attempted Arab outreach this election, but the destruction of this taboo benefits opposition parties if there is to be another contest. If no majority is inaugurated this cycle then these future political developments and the forces of necessity will likely birth a new government after a fifth election.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.