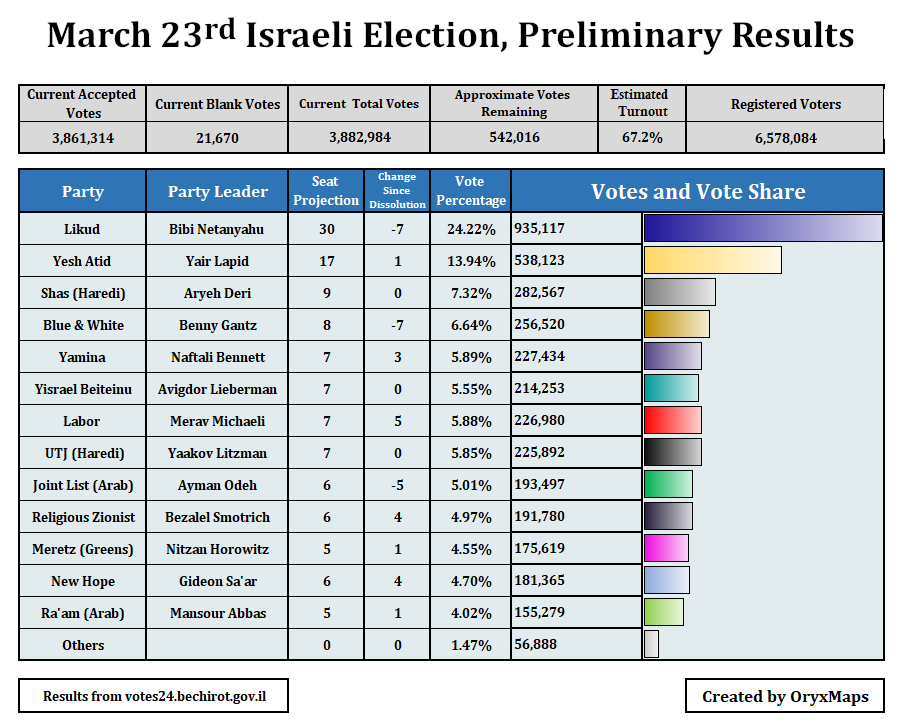

The Israeli electorate voted yesterday, March 23rd, and the final results are still unknown. Enumerated votes are reported via the government from over a thousand municipalities across Israel and the West Bank settlements. The numbers presented in this article might have changed already, and will change more. The complete official count will not be known until at least Friday the 26th. It appears that the uncertainty which prompted the repeated 2019 and 2020 Israeli elections continues. Projections say that neither Likud’s nor the opposition’s ideal government has a majority of seats in the Knesset.

Turnout

Close to 67.2% of registered voters participated in this election. This is 4.3% lower than turnout in 2020, which diverges from the pattern of voter turnout increasing each repeated election. It appears fear of the Coronavirus and electoral apathy negatively hurt turnout. Only active members of the military, government employees (e.g. diplomats and their staff), and individuals whose occupation or situations prevents them from utilizing the Election Day holiday (e.g. hospital workers and patients) have the option to vote in advance. “Special” advance voters are not included in the total turnout number, so the final turnout will marginally increase. Israel instead offered drive-through no-contact voting stations for those concerned about infection and quarantined voting sites for those currently self-isolating. The number of polling sites was additionally increased to limit crowding and maintain distance.

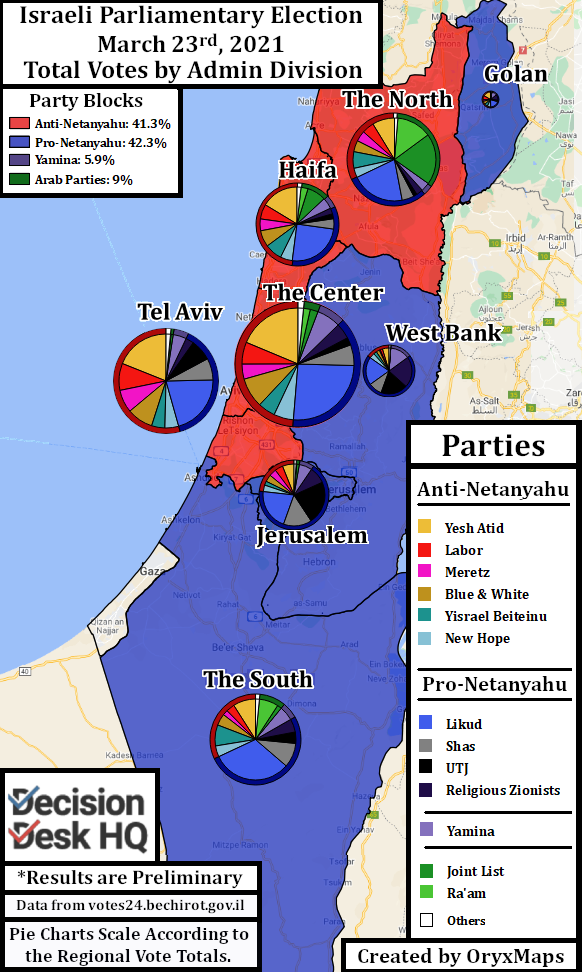

Turnout among Israeli communities varies. The highest turnout rates are always in exclusively Haredi areas, and the lowest are always in exclusively Muslim Arab localities. Over 70% of voters in the Haredi suburb of Bnei Brak voted in both 2020 and 2021 for instance. Arab turnout rates improved during the three previous elections, a development that allowed the Arab Joint List to win more seats than any previous combination of Arab parties, but turnout rates still remained below that of any Jewish community. Arab turnout rates appear to have decreased from the high point in 2020, but to varying degrees. Some areas that overwhelmingly backed the Joint List in 2020, like Basmat Tab’un, Ras Ali, and Jatt, all saw turnout decrease by over 30%. Arab Areas where a portion of the population voted in 2020 for Secularist parties, like Nazareth and Maghar, saw smaller turnout drops closer to 10% of the voting population.

Why these Results

Exit polls project Likud to win 30-32 seats, the most seats of any single party. This was expected by pre-election polls and parliamentary actors because no united opposition ticket formed to oppose Netanyahu. Yesh Atid and the opportunistic Benny Gantz united their prospects into the Blue and White alliance to challenge Likud in 2019, and the subsequent elections preserved the alliance’s viability. The alliance fell apart in 2020, with Gantz supporting the emergency government and Yair Lapid taking Yesh Atid into opposition. Yesh Atid presently is the second largest party at a projected 17-18 seats, and the remaining Blue and White under Gantz shrunk to a projected 7-8 seats.

Some voters previously represented by Gantz’s side of Blue and White instead voted for the New Hope party under Gideon Sa’ar. Sa’ar previously was a Likud cabinet minister with leadership ambitions, but three successive elections convinced him that Netanyahu would not willingly cede power. Sa’ar failed to defeat Netenyahu in the 2019 Likud Primary, and is projected to now won 6 seats in his bid to deny the Prime Minister his majority coalition at the ballot box.

Every Israeli political party dedicates the last few days of the campaign to Gevalt political tactics. Gevalt is when political parties knowingly lie about their projected electoral fortunes or stoke fear that electoral rivals will get power, in an attempt to motivate their supporters to vote. Admitting that one’s political party faces defeat normally disheartens voters and turns them away from the polls, but this tactic works in Israel because of the country’s small size and factionalized electorate. Some electoral positions, such as being on the edge of the 3.25% threshold, benefit from Gevalt because there is real fear of the party getting no seats and wasting votes, and different political factions react differently to the tactic. Likudite Gevalt consistently hurts National Religious parties; Yamina polled at 10 seats but is projected to win 7. Likud’s large lead led to a unusual Gevalt campaign designed to boost the Religious Zionist Alliance and protect it from the threshold. The Religious Zionists benefited and went from a polled 5 seats to a projected 7. Tactical application of Gevalt allowed Meretz (Greens) and Labor, the two minor Secular parties, to both win a projected 6 to 8 seats. United Torah Judaism and Shas, the two Haredi parties, pull from a consistently stable electorate resilient to Gevalt. UTJ is projected to win 7 seats and Shas is projected to win 9 seats, the same numbers as in 2020.

For the first time, Likud made an appeal to overwhelmingly Arab communities. The purely Arab parties do not control the Arab vote, and there have always been Arab factions that preferred Likud or an opposition party. This election was the first time recently a big party attempted to directly appeal to the Arab electorate, because previously this move would invite attacks from rival, Jewish political parties. Only Likud has the soft power within the Israeli arena and the potential political capital from the “Abraham Accords” agreements with Arab nations to make such a move. Opposing parties argued that this was an insincere campaign that only emerged because Arab turnout surged to an unprecedented level in 2020 and overwhelmingly voted for Likud’s rivals. From the detractors’ perspective this was a divide and conquer strategy. Likud put up ads in Arab neighborhoods and convinced the Islamist Ra’am to leave the Arab Joint List. At the same Likud formed pre-election agreements with the Religious Zionist Alliance and their Kahanist (Jewish-Supremacist, strip all Arabs of citizenship) Otzma Yehidut member party.

Likud’s campaign however appears to have succeeded in a peculiar way. Likud rose from 0% of the vote to the percentage of the vote that backed Secular Jewish parties in 2020, but almost never any higher. Likud appears to have won those factions of Arabs already open to voting for Jewish parties. The traditional Joint Arab List is projected to win 6-9 seats, and Ra’am may win 4-5 seats or it may fall below the 3.25% threshold. Some Arab voters that previously voted for the Joint List appear to have voted for smaller Secular parties, preserving these tickets from the threshold.

The Consequences

This election was about Netanyahu. Absent was the question of Palestine, and the vaccination dilemma was sidelined. Tens of thousands of Israeli’s protested this Sunday, not against Likud but against Netanyahu personally. When compared to the previous three elections though voters elected more parliamentarians with flexible views on renominating the Prime Minister. The emergency government broke the deadlock of clear pro and anti Netanyahu blocks, and the chaotic experience of the emergency government prompted a common desire to avoid an immediate fifth election. It was previously in Likud’s interest to continue holding elections because Ministers in Israel retain their positions between elections. Likud kept control of power even though there was no coalition. The emergency government’s arrangement however gave some power to the Blue and White Secularists, and this government would continue if no coalition agreement is signed, hampering Likud’s policies. Several parliamentary groups have expressed interest in nominating Netanyahu or the opposition because there are now incentives for both to form a government.

Neither Likud’s ideal coalition nor any hypothetical opposition alignment is projected to receive a majority of seats in the Knesset. This election does not differ from the past three elections which all returned majorities for parties opposed to reelecting Netanyahu. Although the opposition should receive a majority, it cannot unite because the Arab parties and Secular Israeli nationalists refuse to work together. A new majority must be sought if Israel is to avoid an undesirable fifth election.

Likud is the largest party, has a monopoly on unofficial political soft power, and has the most potential parliamentary allies supporting them. There is no unified Blue and White opposition ticket that can command a similarly sized slate of parliamentarians. An opposition candidate can only inaugurate a government if the projected results shift in favor of the opposition or the Arabs and the Israeli nationalists resolve their differences. If there is to be a government, Netanyahu will lead it. The composition of this likely Likud coalition is unknown. Gideon Sa’ar and New Hope successfully denied Likud a majority, and Sa’ar repeated his opposition to Netanyahu on election night, but the former Likudites elected under the New Hope label may defect for personal power. Yamina may prefer working with Likud, but Likud lacks an easy majority. The vastly diminished Blue and White may return to Likud in the name of stability, even though Likud’s unity government was anything but stable. There is the potential for Ra’am to support Netanyahu’s government in exchange for direct relief and aid for Israel’s Muslim community, if Ra’am remains above the threshold. Ra’am and Likud’s National Religious allies however refuse to support a government the other backs. The future is uncertain and everything hinges upon whether compromise is even possible.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.