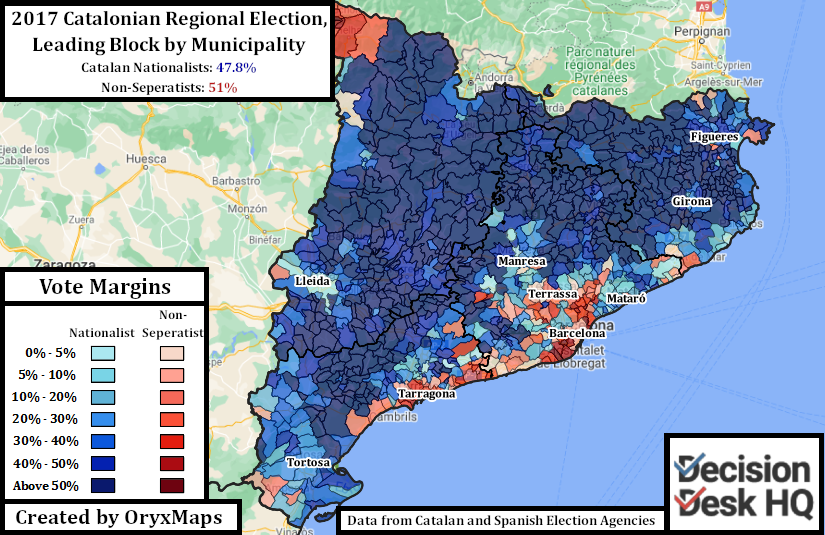

Catalonia, a Spanish Autonomous Community and subnational Nation home to just under 8 million people (a similar population to Washington State), goes to the polls on Sunday the 14th. If an outsider has a prior image of Catalonian politics, it is likely one of protests, separatism, and the confrontational news stories that emerged from 2017 and 2019. This picture isn’t entirely inaccurate; the questions of belonging and identity were at the center of Catalan politics long before 2017. However, there is more to Catalonia than just the political jostling between the 50% of the voting population who support independence, and the 50% content within Spain.

A Brief History

Up until the 15th century, Catalonia was the political center for the Crown of Aragon, a separate entity from her Castilian neighbors. The marriage of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile brought the Catalan and Castilian realms together, but each was governed under its own traditions and laws. It was not until the war of the Spanish Succession in the 18th century that the new Bourbon kings abolished the Crown’s autonomy. Various actors in civil society during the 19th century kept the Catalan culture alive and planted the seeds for a national identity.

Catalonia received autonomy from the Second Spanish Republic of 1931, a product of the regions increasing nationalism and the new Republic’s distaste for centralization. The Spanish Civil War resulted in General Francisco Franco revoking this autonomy, banishing or executing all separatist leaders, and restoring centralism upon victory. Franco banned the use of Catalan as an official language and promoted Spanish.

Franco’s death in 1975 began Spain’s transition back towards Democracy. Catalonian voters approved the new federal constitution and the subsequent statute of autonomy by overwhelming margins. For the next 20 years, Catalan politics were dominated by Jordi Pujol and the big-tent Democratic Convergence Party (CDC). The goal was nationalism, identity, and cooperation with Madrid, not outright separation.

Pujol’s retirement in 2003 brought to power a left-leaning coalition of the Socialists’ Party (PSC), the Republican Left (ERC), and the Greens. This government negotiated a second statute of autonomy, but the conservative People’s Party (PP) challenged its constitutionality in court. When the challenges were finally settled in 2010, the courts threw out all the provisions important to the Catalonian identity. This decision triggered a revitalization of the Catalan separatist movement, and returned the CDC to power – albeit in a nationalist coalition with the ERC.

In 2014, the Catalonian nationalist government sponsored the first modern independence referendum. Most (81%) voted for independence, but the poll lost legitimacy because only 42% of voters cast a ballot. The CDC would split up afterwards, partially because of disagreements over the independence movement and partially do to incriminating revelations about former leader Pujol’s corruption. The remnants sponsored a new Catalonian nationalist government in 2015, albeit one that only received 48% of the vote between the constituent parties.

The Road to 2021 the Election

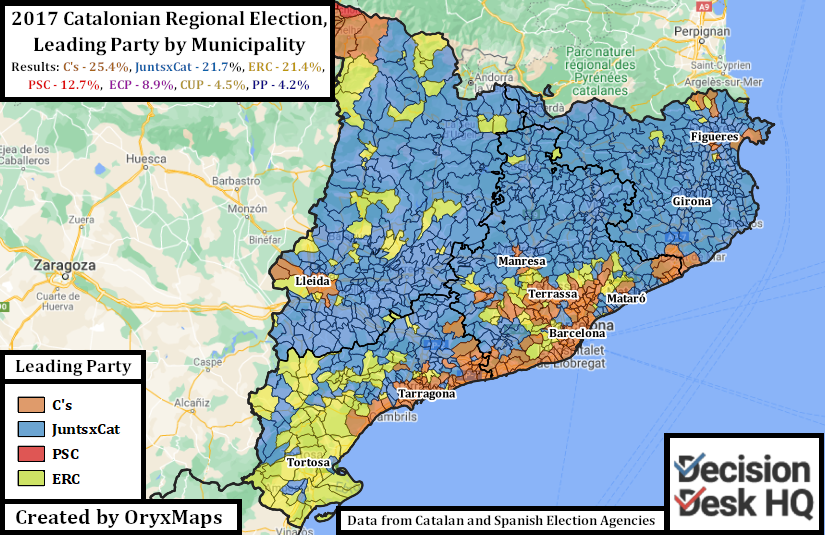

The new government elected Carlos Puigdemont as President of Catalonia in 2016. His new government approved a second referendum in 2017 and passed separatist legislation – all considered illegal by the PP Madrid government. This confrontation led to the events of 2017, where the PP government – legally in the right according to Spanish law – ordered police into Catalonia to stop the referendum. In response to the nationalists continued to push for independence, Madrid suspended Catalonia’s autonomy, dissolved the Catalonian government, and arrested several leading ministers. Subsequent elections returned the Catalonian nationalist coalition to power, but once again with less than 50% of the vote. Puigdemont fled the country, escaping Spanish arrest warrants.

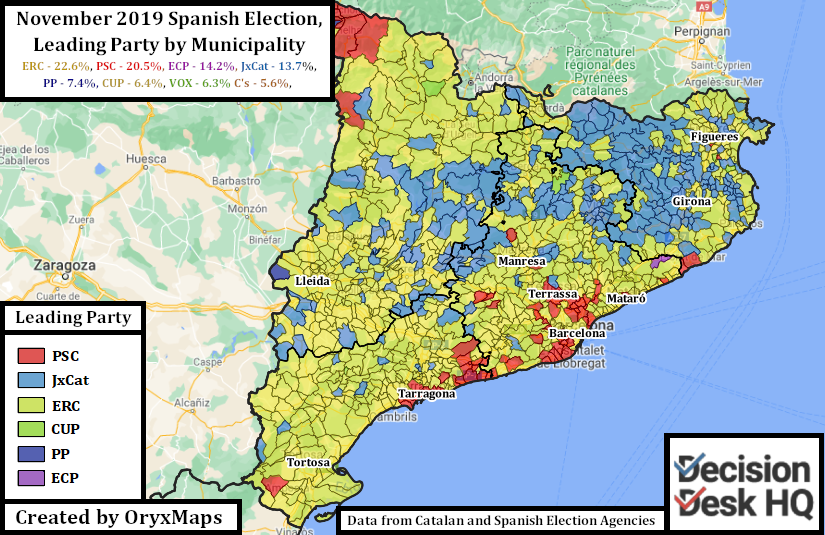

The new government tried to restore their former leaders, but facing opposition from Madrid, elected Quim Torra as President of Catalonia. Spain then began the trial of the twelve ministers arrested on charges of treason, an investigation that would only end in 2019. All accused received some form of punishment, which triggered more protests across Catalonia. Protests escalated into riots. The courts additionally sentenced Torra with fines and temporarily barred him from holding office. Torra’s inflexibility and the nationalist coalition’s breakdown ensured new elections would happen eventually. The COVID-19 pandemic though postponed a new vote until 2021.

Electoral System

Spain, and therefore Catalonia, uses the D’Hondt method for allocating seats. Votes and seats are counted, and awarded proportionally, by region. There are 135 seats total. All parties under a 3% threshold earn no seats. This system favors larger parties and parties that win seats in rural areas. This has historically benefited the Catalan nationalists and allowed them to form majority governments without winning a majority of the vote. Voter turnout is expected to be comparatively low this year because of COVID-19 precautions.

Contesting Major Parties

Separatists

Together for Catalonia (Junts per Catalunya or Junts): Polls between 19% and 21%, or 29 to 34 seats. Junts is a big tent separatist party, and is the current vehicle of those previously aligned with the CDC. Junts is loyal to, and led by, former President Puigdemont. Junts formed because Puigdemont’s allies lacked control over their previous electoral vehicle. They advocate for unilateral and immediate implementation of the independence manifestos from 2017.

Republican Left of Catalonia (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya or ERC): Polls between 18% and 21%, or 28 to 33 seats. The ERC is a left-aligned Catalan nationalist party with deep roots. The party is led by Oriol Junqueras who was arrested and imprisoned in 2019. Former Vice President and now acting President Pere Aragonès leads their electoral campaign. The ERC electorate has grown more pragmatic towards working with the Spanish government, whereas their rivals in Junts increasingly favor a rupture. Abandoning the 2017 militancy would cause an exodus of voters to Junts, so the ERC campaigns as a separatist party.

Popular Unity Candidacy (Candidatura d’Unitat Popular, or CUP-I): Polls between 5% and 7%, or 7 to 10 seats. The CUP is the urban far-left branch of the nationalist tree. Along with separatism, the CUP supports a program of nationalization, environmentalism, and lowing the voting age.

Catalan European Democratic Party (Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català, or PDeCAT): Polls between 1% and 3%, or 0 to 2 seats. The center-right rump remainder of Puigdemont’s former electoral project.

Non-Separatists

Socialists’ Party of Catalonia (Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya, PSC-PSOE): Polls between 20% and 23%, or 29 to 34 seats. The PSC is a devolved branch of Spain’s main party of the electoral left, the PSOE, who control government since the 2019 elections. The PSC opposes separatism but favors federalism. The public face of Spain’s Coronavirus response, health minister Salvador Illa, assumed leadership of the PSC in January and the party’s fortunes immediately improved. PSC’s gains have led to all other parties, especially Junts, into attacking the PSC. Junts fears that if PSC tops the polls then Illa will woo the ERC away from the separatist camp and into a coalition of the political left.

Citizens (Ciudadanos, C’s): Polls between 6% and 10%, or 8 to 13 seats. C’s is collapsing. C’s commits itself to liberalism and democracy, but also to the indivisibility of Spain and an opposition to Catalan separatism. The party benefited from the violence of 2017 and topped the Catalonian polls in the 2017 election, but was unable to form a government because Catalan nationalists held a majority of the seats. The swift rise of C’s nationally in 2018 and 2019 led to its aborted attempt to supplant the PP as the main party of the electoral right, a move that fractured the parties’ emerging coalition. Liberals were disenchanted by this move and shifted towards the PSOE, and the failed attempt to woo the Liberals back pushed the Spanish nationalists towards VOX.

In Common We Can (En Comú Podem, ECP-PEC): Polls between 6% and 9%, or 7 to 12 seats. The ECP is the Catalan branch of Podemos, the insurgent left party which emerged from the backlash to Eurozone austerity. The party’s base is urban and young. Unlike every other notable party, the ECP does not support either side in the independence debate. The ECP supports a legal referendum on Catalan nationalism, approved by both Madrid and Barcelona, which will then be acted upon – no matter the outcome.

VOX (VOX): Polls between 5% and 8%, or 5 to 10 seats. VOX is Spain’s version of the right-wing populist party. Spain’s authoritarian and Francoist history differentiates VOX from similar parties across Europe, and has lead to an electoral base that is more wealthy and white-collar. VOX’s confrontational attitude towards the separatists has made VOX both their target and an attractive vehicle for Spanish nationalists, leading to limited gains in the polls.

People’s Party (Partit Popular, PP): Polls between 3% and 5%, or 3 to 5 seats. Spain’s main party of the political right has never enjoyed significant support in Catalonia. Their fortunes have only worsened with VOX and C’s competing for the same electorate.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.