While the story of the UK Election is mostly in the results in England and Wales, the reason Boris Johnson has the majority he now has, the results in Scotland and Northern Ireland don’t match the national trend. And, perhaps more importantly, they may signal the end of the United Kingdom as it currently sits.

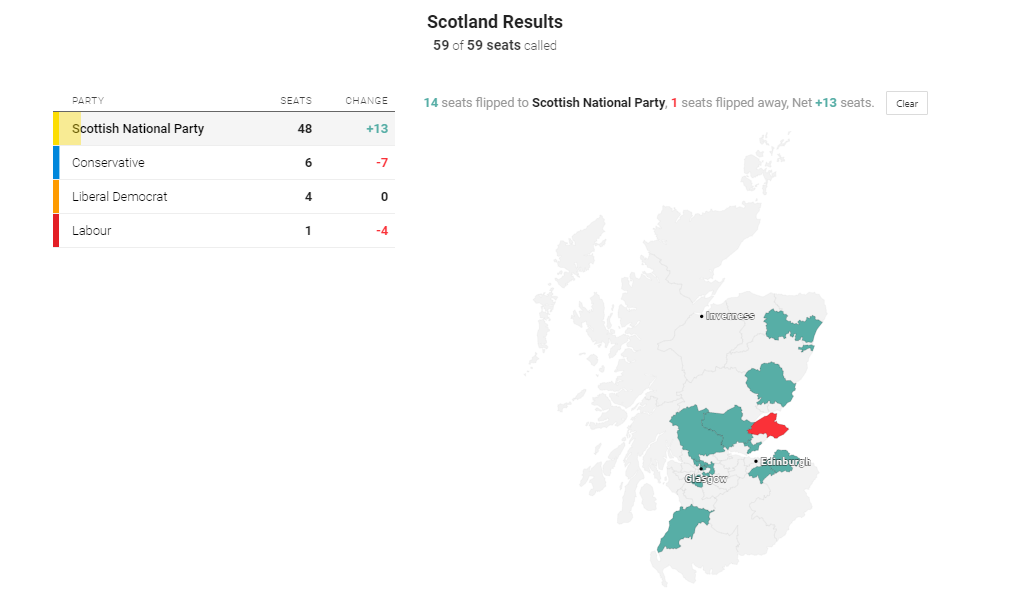

We have to start with Scotland, and in doing so, appreciate that the SNP’s 13 seat gain is still a very impressive result, even if they didn’t win the 55 the exit poll had.

Their 45% of the popular vote matches their Scottish Parliamentary highs of 2011 and 2016, and definitively proves that the Nationalist tide north of Hadrien’s Wall is not receding. The SNP are going all in on a second referendum for Scotland, on an offer of independence from the UK and re-entry into the EU, a proposition that should go over well with the 62% Remain electorate. The 46% of the vote which went to explicitly pro-Independence parties – including the Scottish Greens, themselves independent of the English and Welsh Green Party – is not enough for a referendum win, but given Jeremy Corbyn’s promise to hold a Scottish Referendum after the first year of a government he led means that some Labour voters were also pro-independence. Put another way, three parties gained share of the vote in Scotland between 2017 and 2019 – the SNP, the Scottish Greens, and the Brexit Party, and two of those three parties were pro-secession.

The Westminster government does have final say on the legality of a referendum, but it would be hard to see how Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon could be denied that this is a mandate for another vote – an 8.1% vote share increase when the party ran on an explicit referendum position seems unambiguous. Additionally, some raw politics may be in play here – Boris’ majority would spike if Scotland voted to leave, with his Majority of 80 becoming a majority of 127 overnight, without having to do anything. The task for Labour getting back into office would become even harder – as without either Labour or SNP MPs from Scotland, they’d only have governed for 8 years since the 1960s. Scottish members won Labour government in October 1974 and 2005, and without that, they need to have a Blair-sized landslide in the south and suburbs to make up for the new map. If Boris Johnson thinks the political damage in England and Wales of letting Scotland leave is outweighed by the sheer math, he may just let Scotland do what it wants anyway.

Would the SNP win such a referendum? It’s unclear. The polls of Scotland from before the election would say no, with Survation having it 49/51 for leaving. However, that poll also understated the SNP’s support, so it’s entirely possible the support for independence is missed by the same polls which had unionist parties doing better than they did. A first blush at a race rating for a potential referendum would be Lean Independence – but one also remembers the history of Quebec, where in 1992 and 1993 secession would have easily passed, but by the time of the referendum in 1995 it barely failed. There’s no certainty that same pattern would repeat, but that does inform the caution in assuming it’s gone.

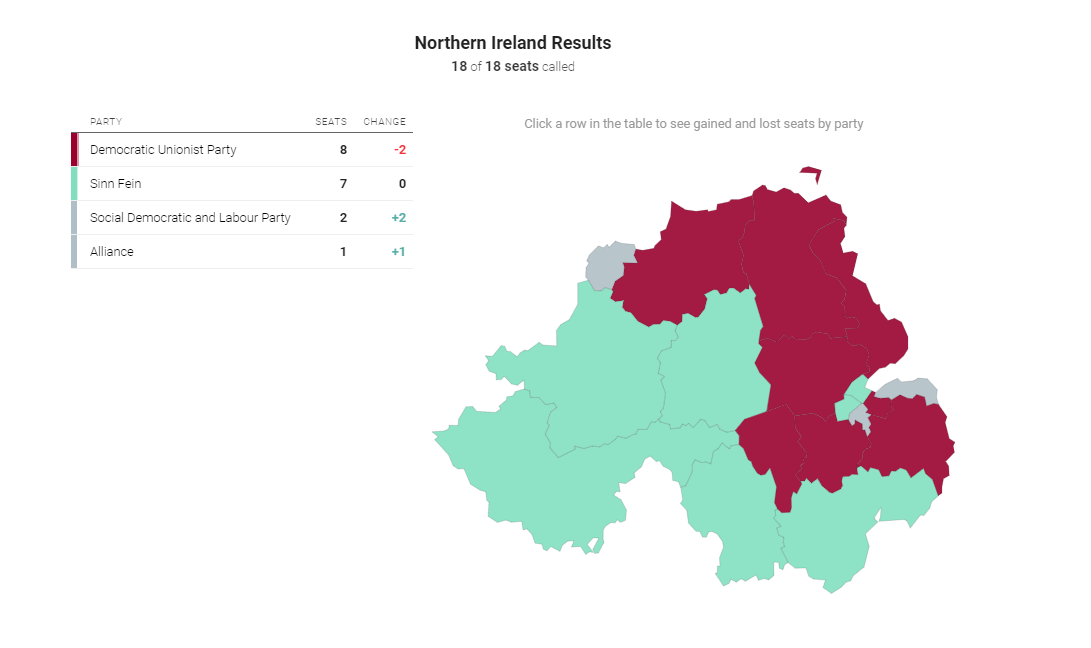

The other part of the Kingdom that suffered an increased risk of dislocation was Northern Ireland – after two elections wherein 11 winning candidates were avowed Unionists, and 7 were nationalists, this election saw the loss of 3 unionist candidates to either nationalists, or the abstentionnistes in the Alliance. From a clear majority of Northern Ireland’s Westminster delegation being Unionist to a plurality being against it, the chances of some form of border poll – a referendum on Irish Unity – spiked. Issues around the placement of the UK-EU border – basically, where the customs checks for both goods and persons will be – was the basis of much Brexit wrangling, and Boris Johnson had to agree to move the border from the island of Ireland to the Irish Sea to get his Brexit deal. In effect, Northern Ireland will remain de facto in the EU, and this fact represents the biggest change in Northern Ireland’s constitutional status in the UK since the Good Friday Agreement. Northern Irish people are going to be treated differently than Brits – and if that’s the case, the union has already been broken. The timeline for formalizing that process is unclear, but UK law mandates the Secretary of State For Northern Ireland to hold a border poll if there’s a good prospect of success, so in time one will be held.

These two stories make sense together, when one remembers that both Scotland and Northern Ireland voted for membership of the EU, and Wales and England voted out. If the UK becomes England and Wales – a prospect that now needs to be taken seriously – then the chances of the left in its current iteration winning power anytime soon are low. It would force Labour and the Liberal Democrats into a place of needing formal cooperation every election – which, they needed this time anyways. It would also reduce the chances of the UK rejoining the European Union anytime soon, just as counting Florida’s votes without Dade county would make the Democrats much less likely to win it. The United Kingdom is more disunited than it’s been at any point since the various moments of crisis during the Troubles. Just how disunited it can get, and how quickly, seems to be the only question left.

Evan Scrimshaw (@EScrimshaw) is Managing Editor and Head Of Content at LeanTossup.ca and a contributor to the Decision Desk HQ.