Winning election to the Dutch House of Representatives (the Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal) is simple when compared to almost every other electoral democracy. One can win a parliamentary seat if they convince approximately 62,000 citizens to vote for their ticket. This is the advantage of a near fully Proportional parliamentary system with no percentage threshold requirements.

There are however downsides to this system. The proliferation of political parties renders coalition construction difficult. There is little incentive for comparatively larger parties to compromise with the multitude of very small or tiny parties that can only add one to three seats to the coalition, locking these tiny parties—that combined represent about 13% of Dutch voters—out of policymaking. Political cordons, ideological rivalries, and parliamentary fragmentation ensure that entry into a governing coalition is only an option for the same few parties each electoral cycle. In the Netherlands, consensus trumps change. That is expected to continue when voters go to the polls tomorrow, March 17th.

The System

Dutch electoral outcomes appear consistent with the political science principle of Duverger’s Law. This observation recognizes that First-Past-the-Post systems trend towards two political blocks whereas Proportional Systems trend towards many parties. Parliamentary fragmentation is normal when the barriers to parliamentary entry are low, and Dutch elections are fully proportional with no threshold. Voters are required to select a preferred regional candidate within their preferred party, a peculiarity that leads to extraordinarily large ballots. This feature does not alter outcomes; winning 0.67% of the vote equitably translates to one seat out of 150.

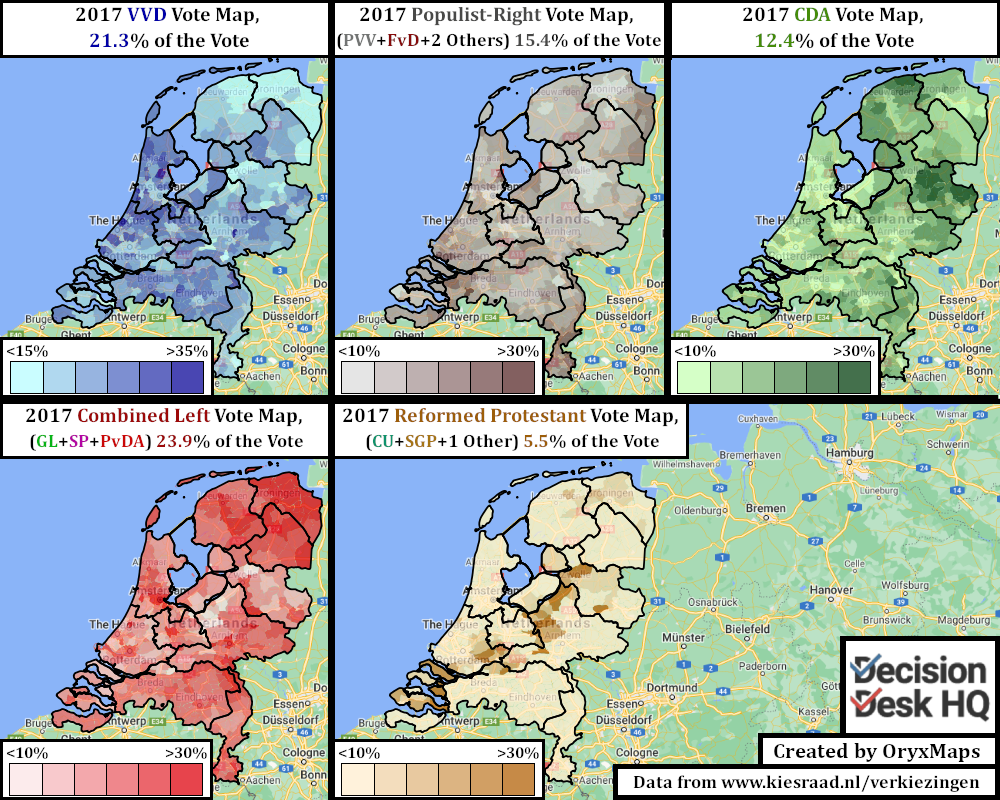

The exponential surge of viable parties however only began within the last 30 years. Dutch society in the 1920s, when the country first voted under proportional representation and universal suffrage, was self-segregated into social ‘pillars,’ or pillarization. The Catholics, religious Protestants, Socialists, and Liberals each had their own schools, unions, newspapers, sporting teams and, especially, political parties. Parties campaigned within one of these four pillars and governing coalitions emerged from the cooperation of two or three of the pillars. Tiny parties existed, but with little room to maneuver.

This phenomenon persisted until the 1960s when increased wealth, education, and social mobility led to the Baby Boom generation rejecting pillarized social institutions. New, anti-pillar parties emerged to represent the new voters, but the pillarized parties remained dominant through the inflexibility of voter identities. It would take another 30 years of generational turnover for pillarized voting patterns to dissolve into the recognizable fragmentation.

The Outcomes

Full proportionality and political fragmentation lead to two uniquely Dutch electoral outcomes: a large number of tiny parties and the proliferation of viable medium-sized parties. Both outcomes are possible because the amount of votes received by the larger parties has plummeted. Some tiny parties are single-issue, such as the pensioner 50PLUS, while others cater to small demographic subsections, such as the Turkish-Dutch DENK. These parties remain permanently in the opposition by design. Parliamentary representation serves more as a forum for advocacy and a chance to vote on issues brought forward by the government relevant to said niche electorate.

The medium-sized parties, in contrast, put forward a national platform and try to appeal to a wider electorate, but the multitude of options presented to voters prevent each single party from dramatically increasing its size. Some are old formerly-pillarized parties that adapted to the modern system. Others are the beneficiaries of the pillarized system’s collapse. All either campaign to enter government, which necessitates compromise with the party leading the polls, or campaign to lead the opposition, because ideological objections preclude compromise with the leading parties’ policies.

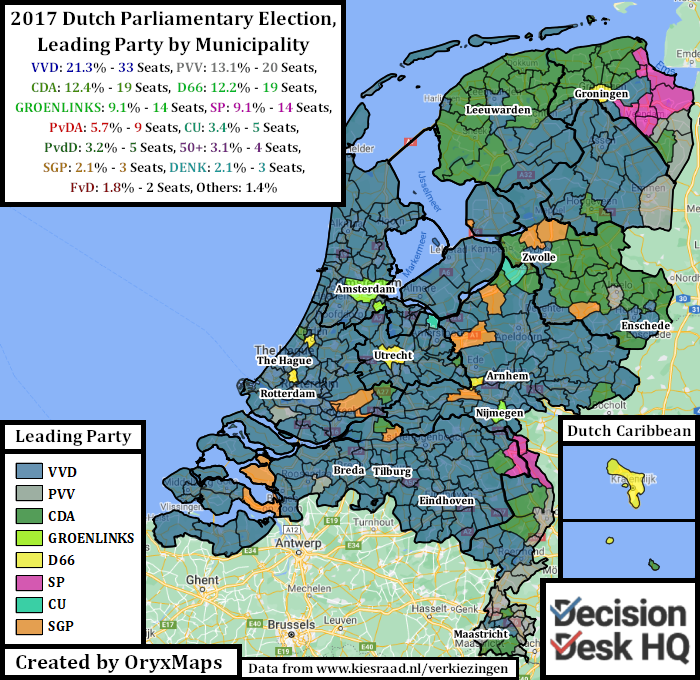

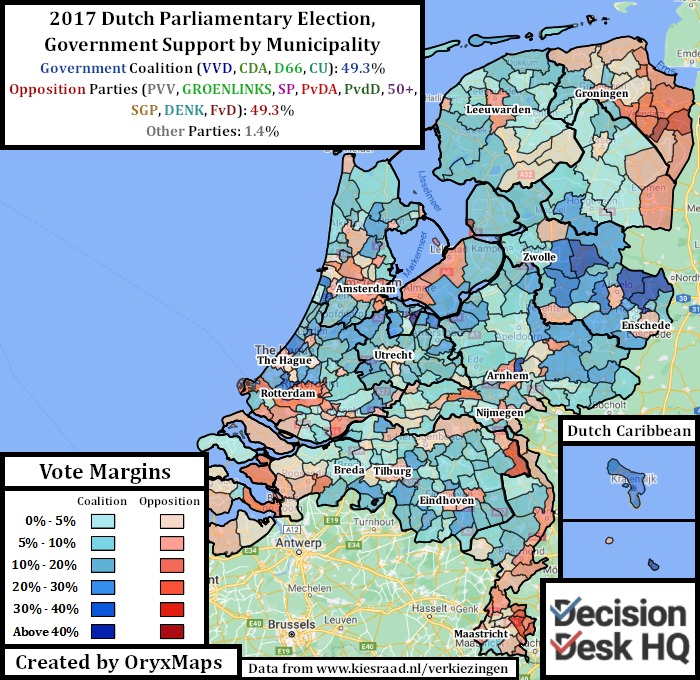

Incumbent Prime Minister Mark Rutte’s economically liberal People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) has won all three Dutch General Elections since 2010, and polls suggest this will continue in 2021. Dutch polls project the VVD will win approximately 10 to 20 more seats than its nearest competitor when polls close on March 17th. Government formation will be less simple. 2017’s formation process took 225 days, the longest in Dutch history, and the resulting coalition contained four parties – the most since pillarization ended and the allied Christian parties consolidated into one ticket. The VVD refuses to work with the right-populist Party for Freedom (PVV), led by Geert Wilders, and the Socialist Party (SP) is ideologically opposed to working with the VVD. Removing these parties and the tiny parties’ seats and votes from the calculus leaves only five potential coalition partners for the VVD – the same five previously considered for the governing coalition in 2017 and in years past.

Theoretically, polls suggest that the incumbent coalition will receive more seats than in 2017. Some scenarios suggest that the government could drop the smaller Christian Union (CU) and return to power as a three-party arrangement between the VVD, the once-dominant (and once-pillarist) Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), and the once anti-pillarist but now social-liberal Democrats 66 (D66). Yet this governing coalition lacks a majority in the vestigial Senate (the Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal, elected in staggered elections by a complicated formula to proportionally represent the composition of provincial legislatures), and the VVD might prefer a combination of parties that can command more votes in that chamber. The Senate’s only power is to vote yes or no on bills, but the lack of a concrete majority prevents easy implementation of major legislative proposals. No matter the post-election coalition, consensus will continue.

Ben Lefkowitz (@OryxMaps) is a Contributor to Decision Desk HQ.